After building the power plant, more than a dozen kilometers of the Daugava gorge were flooded, including an unusual 18-meter high cliff called Staburags, which was considered to be one of the most beautiful points of interest in Latvia, reported a story on Latvian Radio on Monday.

People are still divided on whether the economic gain is worth the cultural cost, though it is too late to do anything about it.

Divers say the Staburags cliff, once a towering sight, is covered with freshwater snails. The peak of the cliff is now 6.5 meters below water, and tree stumps and branches mark the historical site. Divers hunt for souvenirs from the foot of the cliff, still within the memory of many men and women.

While the heads of other dolomite cliffs can still be seen in the area - mostly some few meters above the water.

"The water was about 250-300 meters wide here. Now it's about 950 meters, when looking diagonally from my house. There were in fact places that could be forded when the summer was dry," said Gintars Zoltners, who lives nearby the cliff.

Tourists often think that the house of Māra Svīre, a writer who settled down near Staburags after it was flooded, is a museum.

She recounted the memories of the previous owner of the house, Marta Gulbe, who had seen the flooding of the cliff. She had once walked to the riverbank and pointed her finger, saying: "Here, here down below is the Staburags!".

The first year after the HPP was built, the cliff was flooded halfway. Then came winter, and the river froze. The last part of the flooding took about a week, said Svīre.

Before the Pļaviņas plant was built, the Daugava river flowed from Pļaviņas to Koknese in splendid a gorge with dolomite cliffs towering some 30 meters above water. The gorge had been a popular tourist destination starting from the 1850s. The crown of the gorge - the Staburags cliff - was as high as a six-story building, and the springs that flew from it took an astonishing beard-like look upon freezing in the winter.

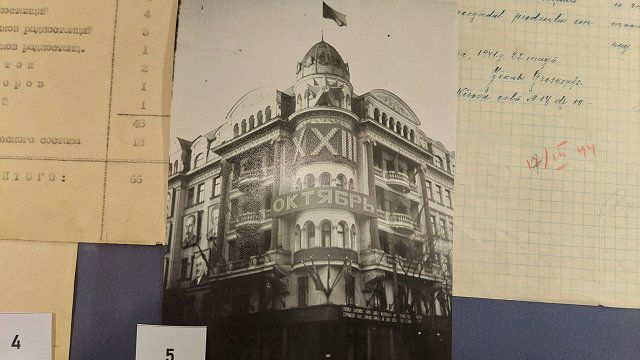

A video from the Latvian National Archive shows the surrounding areas in a 1939 chronicle by Eduards Kraucs.

Meanwhile, the engineers of the project think that building the plant was economically justified and well founded even today.

When there wasn't any hope to stop building the plant, people flocked to see the place for the last time in 1965. Harijs Jaunzems, who was the main engineer of the project, and later the whole Daugava power plant cascade, tells of other plans that could have saved the gorge, but that were not economically feasible - a detour channel that stretches some 40 kilometers, or two smaller power plants that were formerly part of the project.

"It was a purely economic matter. Staburags was the priority - no one really worried about anything else. But it was a decision that the state took: to sacrifice Staburags in the name of the economy," said Jaunzems.

He also stressed the matter of the HPP operating as an emergency power reservoir: "If there's no such reserve that can crank up the output momentarily, then, you know - [at times] Moscow has ran out of power, London and New York have lost it for 6 to 8 hours... Rīga has never run out of energy, because we have the hydroplants," said the energy expert.

Footage from the preliminary works on the dam show the narrator speaking in exalted tones: "80 tipper trucks are storming the surging current. At 11.10 the river banks have met. The victory of the constructors honors the anniversary of Soviet Latvia."

The HPP named after the town of Pļaviņas is actually situated some 40 kilometers away in the city of Aizkraukle - previously named Stučka - that was built during the construction of the dam. The huge plant divides the raised "sea" before the dam and the former course of the river some 40 meters lower. The dam was built in five years, and now accounts for 25 to 30% of the total electricity produced in Latvia, employing 80 people. It also houses a small museum that shows construction works and the flooded Daugava gorge.

Historian of the Daugava Museum, Mārtiņš Mintaurs, who had conducted extensive research, compiled in the Atmiņu Daugava (Memory Daugava) book, said that not only economic motives were behind going forward with building the plant here. It was also politically expedient for Arvīds Pelše, then the Secretary of the Latvian Communist Party, who used 'nationalist' protests to politicize the case of building the dam, in order to aid his own career.

Commenting the symbolical implications of building the plant, he said: "When we hear the argument that, 'Well, it was nothing too good, but everyone needs electricity', I think it's a bit demagogic. We can equally well say that you cannot destroy national symbols and then pretend nothing happened."

Those who lived in the now flooded areas remember the hustle and bustle of the preliminary works.

Graves were moved, houses blown up, trees cut down. Those who were forced to move were given scant compensations, but they were nowhere near enough to build a new house, remembered Zane Niedre, one of the people who lived near the site.

"Others can go to a school anniversary, but my school exists no more," said Zane.

Besides causing the loss of a great national symbol, the inhabitants are sure that the plant is responsible for the spring flooding that is hitting Pļaviņas and Jēkabils particularly hard since the dam was built. Energy experts think that there would be no such problems if the Daugavpils HPP would have been built, completing the plant cascade on the river.

Construction of the Daugavpils dam was stopped in 1986 due to widespread protests, similarly to the plan for building the Rīga metro.

Meanwhile, the people near Staburags have noticed a new cliff growing down the river - a small fountain flows over the lime cliff, slowly but steadily creating a new source of wonder for the generations to come.