Personal tragedy leads to diplomatic action

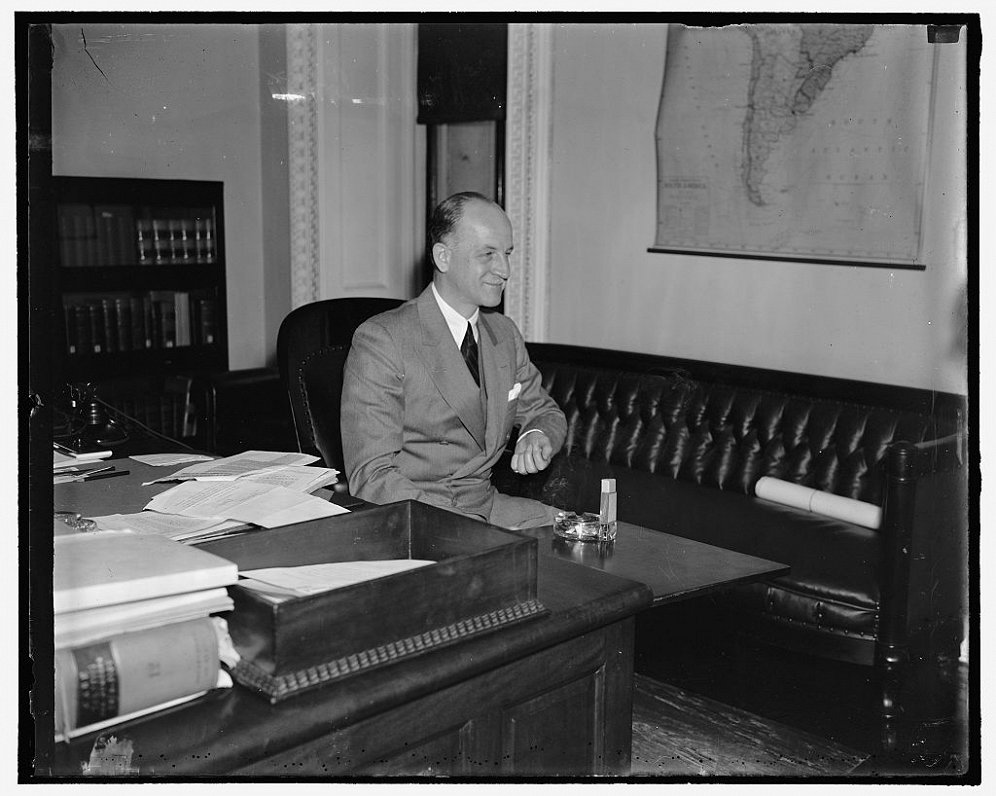

US diplomat Loy W. Henderson was greatly distressed by the events unfolding in Europe in summer 1940. As most employees at the Department of State were focused on the defeat of France, Henderson's worry was compounded by the fate of the three Baltic states. He had firsthand experience there, having arrived in Rīga in August 1919 as a Red Cross volunteer.

In the years to follow, Henderson would routinely visit the fledgling countries and had a stint at the Foreign Service in Rīga. Henderson last visited Rīga in 1938 and liked what he saw. The city was crowded with new and modern houses, with well-off law-abiding citizens walking the central streets. It was the direct opposite of the havoc he first saw in summer 1919. Latvia had beaten all expectations, proving that a small country can remain independent and lead a successful economic policy. In 1938, people could have nursed an optimistic view of the future. But on July 21, 1940 there was no future to speak of.

To Henderson, Latvia was neither something abstract, nor a locus of sentimental memories.

To him, it was personal, because his wife Elīza was Latvian.

As Latvia was occupied, Elīza's family came under Soviet control, including her sister Zenta and husband Teodors. The fate of the Baltics was a personal tragedy to this American diplomat.

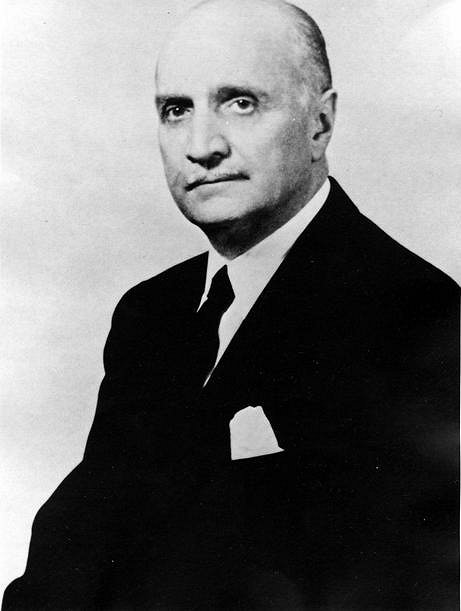

But Henderson's feeling of powerlessness was alleviated by a July 23 talk with Sumner Welles, the Under Secretary of State. Welles wanted Henderson to pen an official declaration expressing sympathy with the Baltics and condemning Soviet action. Henderson duly composed the piece and took it to Welles.

To his great surprise, Welles said that the declaration was not forceful enough. Welles phoned president Roosevelt to confirm his hunch, and the president agreed that the text should have more bite.

After the talk, Welles edited the declaration and, in the afternoon, the declaration signed by Welles arrived to the press and American diplomatic service. With the declaration, the US had expressed clearly that it does not admit Baltic incorporation into the Soviet Union, de facto or de iure.

British hopes

Soviet aggression against the Baltics in summer-end 1940 did not cause international outrage. It was understandable, given the circumstances. South American, as well as the few remaining independent Asian states saw Baltic events as removed from them, and objections against Soviet action were limited to notes of protest. The rest of the world was controlled by Europe, as colonies, dominions and protectorates.

But almost the entire continent was under Soviet or Nazi control. Nazi Germany had started a number of illegal annexations and occupations, and it was therefore unreasonable to have it react. As a German diplomat put it sarcastically, the independence of a single Baltic state was worth less than a single car of fuel that the Soviets could deliver to Germany.

British attitudes were important. Their diplomats had no doubt that the forceful addition of the Baltics to the USSR was a breach of international rights. But unlike the US, the United Kingdom was not ready to voice its protests in the form of a forceful declaration. Remaining alone in the war against Germany, Britain hoped for cooperation with the USSR and therefore, until the end of the war, admitted that the Baltics were annexed de facto but not de iure.

In effect, they hoped to leave the matter unresolved until the post-war peace conferences.

The position of the US and the UK allowed Baltic diplomats to maintain their representation in both countries and preserve a legal basis and institutional framework for the continues existence of these states. This did not do well by the USSR, and from the very get-go Soviet diplomats started pressuring the countries where there were Baltic diplomatic representations. The Soviets said that all Baltic properties, such as apartments, deposits, and archives, should be turned to the USSR immediately. Some countries indeed succumbed to this, such as Petain's Vichy regime, which on August 15 closed off all Baltic missions in France and handed the properties to the Soviets.

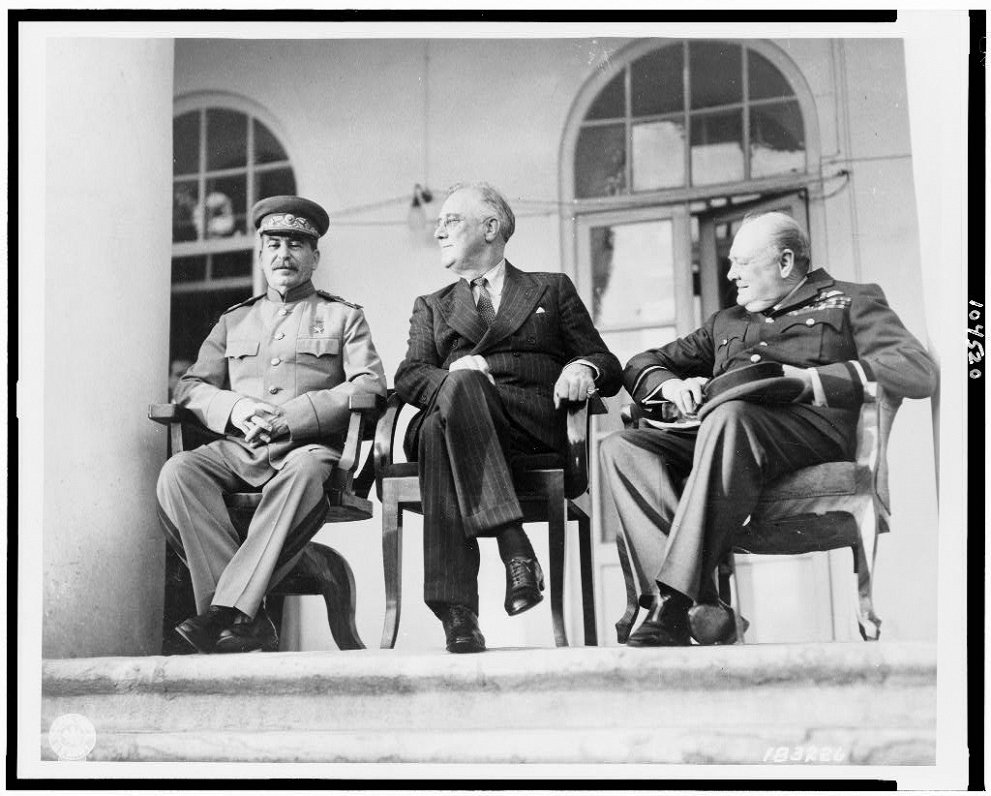

As an alliance was set up between the US, the UK, and the USSR, the Baltic matter was once again brought to the fore. The US maintained a strict position, whereas in the UK there was a group of diplomats who thought it'd be worthwhile to concur to Soviet demands. But as long as the American stance remained strong, such talk was limited to the corridors. During the three big conferences, Stalin asked US presidents repeatedly to legally recognize Soviet claims.

In the first meeting, Roosevelt told Stalin that while the US would not go to war for the Baltics, as long as the matter of their sovereignty is not decided in a free and democratic plebiscite, America would not change its position.

Neither Roosevelt, nor his successor Harry S. Truman would change their position later.

Initial Soviet successes

It was hoped a final fourth conference would lead to a definite agreement about the future of Europe. But it did not come to pass, and therefore the Baltic matter remained unresolved.

For the first years after the war, Soviets enjoyed a good reputation across the world, and there was a risk that part of the international public would acquiesce to Soviet demands. For example, the Provisional Government of Charles de Gaulle found that the stance of the Vichy government served them well, with French diplomats hoping that by acknowledging the new Soviet borders they would have better bilateral relations with the USSR than the US and the UK.

Latvia's de iure representative, diplomat Kārlis Zariņš, was unpleasantly surprised by the case of Argentine, which hitherto housed the only Latvian diplomatic representation in South America. Juan Perón, who was elected president after the war, chose to establish diplomatic relations with the Soviets and acknowledged the borders of the USSR. In 1947 the Argentine government closed off Latvia's mission in Buenos Aires, with the diplomats forced to move to Brazil.

International condemnation

If the Soviets and the Western Allies had come to a wider agreement, it's possible the story of Baltic statehood would have ended there and then. But as early as 1946 there arose tensions, and gradually the two sides came close to open confrontation. The advent of the Cold War became a strong force to preserve the policy of not recognizing the Baltic states as part of the Soviet Union.

In the late 40s, Western countries – including evasive France – declared, one after another, that it was illegal to incorporate the Baltics into the Soviet Union. Several South American countries followed, and the result was an international consensus that the Baltics are not, de iure, a part of the USSR.

As the Cold War became ever colder, support for the Baltics often came from unexpected corners. For example, in 1951 Josip Broz Tito, the PM of communist Yugoslavia, announced that Soviet policies in the Baltics amount to a war crime and genocide. Seeing a chance to become closer to NATO and the US, Spanish dictator Francisco Franco also became a staunch critic of the Soviets and enthusiastic defender of the Baltics.

Firm stance for half a century

The United States was a most fervent and unswerving defender of Baltic statehood. Apart from the US, only the Vatican and Ireland adopted a position of not recognizing Baltic occupation de facto as well. As early as 1946, president Truman and American diplomats did not shy away from pointing out to the Soviets their illegal actions.

At the same time, the American public also started becoming more sympathetic towards the Baltic cause. This was aided in part by the Balts living in the US. But the 1948 law over admitting displaced persons to the country also had a great impact. (Read more about the Latvian DPs here.) The press took a fancy to the Baltic DPs and the US public came to believe that a great injustice had been done to the Baltic states. That the Baltic cause was important to Americans was proven by the fact that both candidates in the 1952 presidential election repeatedly stressed their support for Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia.

It was clear that no matter which party was at power, the US would not forget the Baltics. Despite Soviet objections, the Department of State continued inviting Baltic diplomats to official gatherings.

Throughout the Cold War, Latvian, Lithuanian and Estonian flags flew beside others at the central hall of the Department of State.

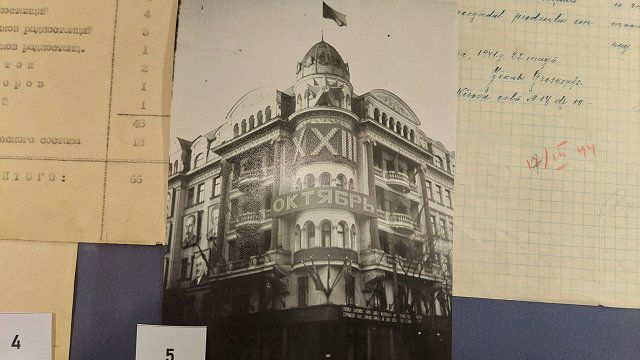

The Department of State also saw to that all official maps showing the European part of the USSR have the following inscribed upon them: "The United States Government has not recognized the incorporation of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania into the Soviet Union."

It is doubtful that, without the unwavering support of the United States, Baltic statehood would have been preserved through the years of occupation. The policies of the United States, a great power, to a large degree swayed the international opinion after the Second World War.

Thanks to the Welles Declaration, a diplomat's familial tragedy caused by the occupation of the Baltics grew into a moral question important to the entire country.