Ksenija: studied only for the Latvian history exam

The 134 questions of the citizenship exam are the basic topics of the Latvian history class taught at school, interspersed with topics from social studies. As I was born in Latvia and went to school here, I had studied the topic at one time. And it seemed I did it well, as history was almost the only class where my grades were constantly high. That's why in this part of the naturalization process I was perplexed not by the difficulty of the task but something else.

By law, Latvian residents who've studied at least half of the school program in Latvian and at a Latvian school are exempt from any exams when they apply for citizenship. It seemed logical at the time when there was no bilingual education or unified exit examinations.

But in 2004 came Education Minister Kārlis Šadurskis, wanting to conclude the introduction of bilingual education in national minority schools. Twelve years later, in 2016, the State Language Center couldn't have been happier about the results of the reform, as now the majority of young people from national minorities know Latvian.

Currently the Latvian exam and education standards are unified for all schools, be they national minority or Latvian schools. The State Language Center said that the content of the history classes is the same at all schools, while learning efficiency depends not on the language of the classes but rather the skill of the teacher.

At that, a teacher at any school and in any language should teach children "awareness of a national identity and statehood, loyalty towards the Latvian state and Constitution, as well as patriotism". So say the upbringing guidelines for students. Any attempt on the part of the teacher to incite their pupils to establish a "people's republic" or any other showing of disloyalty towards Latvia could end in meeting with the secretive Security Police or being sacked. This was introduced not so long ago by the self-same Mr. Šadurskis.

Nevertheless, according to the Citizenship law, Latvian schools produce better, more righteous patriots than national minority schools do.

Question: why, then, does the Ministry of Education bother at all with the national minorities, why does it integrate them in many ways, if twelve years of school isn't enough to make an orderly Latvian citizen doesn't grow out of the little national minority child crying on September 1? Of course the family plays a significant role in forming the views of the child, but the thought that every Russian-language family instills hatred towards Latvia in their children from the very start smells like paranoia to me. Either our lawmakers don't recognize the efforts of teachers and the Education Ministry, or the Citizenship law is terribly outdated.

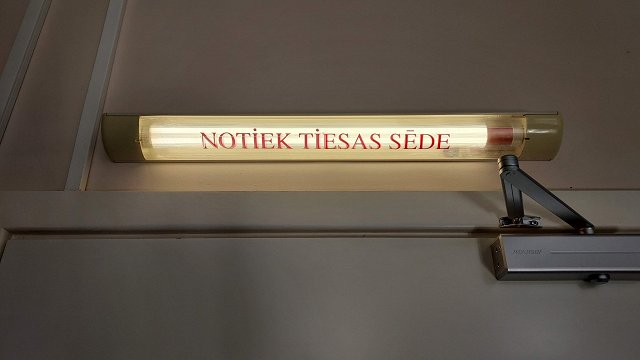

This difference can be considered indirect discrimination and could serve as a reason to go to Latvia's Constitutional Court, said Aleksejs Dimitrovs, a legal consultant at the European Parliament.

While Latvia's Ombudsman Juris Jansons admitted that he personally hasn't studied this aspect of the Citizenship law and that analyzing the educational content would be needed in order to draw a conclusion.

I would perhaps go to the Constitutional Court my self but I have already chosen a different way of obtaining citizenship. That's why I've put aside the disturbance growing in me and instead have opened a history textbook. It was easy to find as there's a small library at Latvian Radio where I found the first edition of Basics of Latvian History. As the book is small and uses easy language, it suited perfectly well for freshening my memory. It can probably be found at any city library but you can also do without it.

There are answers to the questions on the Internet - on the Latvian-language Wikipedia and on different websites.

For example, the Constitutional Court Website has the full Latvian constitution (including a Russian translation). The words to the Latvian anthem can also be found on the web, while on YouTube there's a marvelous record of the anthem from the Song and Dance Festival, to which you can sing along without feeling lonely.

It took me a week to prepare for the exam, and I perused my textbooks for an hour or two after work. If I had studied it without any prior knowledge, it would have taken me about two weeks - the questions encompass the events in Latvia starting from the times when Latvia was inhabited just by a handful of warring tribes.

You can ask for the list of questions at the Citizenship and Migration Affairs office as they sometimes forget to give it to you when you apply.

Anna: Studied for the language and the history exam

Unlike Ksenija, I have to pass the language exam as well. I was rejoiced at first--finally I'll catch up on my grammar! However what followed wasn't as smooth as that and as a result I didn't study for the exam at all. Upon seeing verb conjugation and noun declension tables I began to get sick and I was transfixed by the very thought of sitting down to study. And all that was despite that I like the Latvian language, its poetic manner and sound very much.

At that moment, on the one hand, I wanted to prove to myself that my gradual integration had been fruitful enough to make me able to pass the exam without any preparation.

On the other hand, my unwillingness to study was the result of self-pity and deeply hidden resentment.

A bachelor's paper by Māra Laizāne, Aivita Puriņa and Ilze Mileiko, titled "[The sense of] belonging to Latvia and the identity of students at national minority schools" was published in Rīga in 2015.

It turned out, says the paper, that pupils in minorities' educational institutions feel themselves as belonging to Latvia, its land, nature, and their native city. They don't consider themselves to be Russian but rather Russian-speaking residents of Latvia. Another thing - they don't care about politics at all.

The ties are closer between Latvians and national minorities in the regions but not the capital, and these ties demonstrate a more 'nuanced view towards Latvians' on the part of Russian speakers, who accordingly have fewer stereotypes, as well as more personal experience and positive views.

I can fully attest to this conclusion. At one moment I decided that I don't want to be a lifelong student and started actively looking for a job. And I found it - it was my first Latvian collective. I was thrown into another world and I must say I liked it. It was the first time I saw people who didn't feel lost or alienated from political and social events, which was characteristic of Russian milieus that I frequented prior to that.

However this alienation was not always apparent.

In 2004 Russian speakers faced the fact of reforming the Russian schools after an initative by Kārlis Šadurskis.

I remember that I, too, was skipping lessons and singing 'Black Karlis', not really understanding what it's about. However now, in 2016, I'll say a difficult thing to say--the decision to introduce bilingual education wasn't bad at all.

"This school policy has brought results. The knowledge of Latvian among young Russian speakers isn't a problem. The problem is whether they want to use it to communicate. But that's not a question of language but rather mutual cooperation between the state and the Russian-speaking part of the population [..]

As post-factum research showed, they didn't object as much against the content [of the reform] [..] but rather the way it was carried out. On came Mr. Šadurskis and said, 'It will be as we say! Whatever it takes.' That was the main problem," politics expert Juris Rozenvalds told me.

He thinks the problem lies not in the Latvian-language skills (or lack thereof) but rather in mutual distrust.

This distrust between two ethnic groups gained strength in 2012 as people voted for Russian language as the second official state language.

When the people's vote was taking place, the reason for this bacchanalia seemed to evade me. I saw it was manipulation from certain political forces. As I got older I realized that many Russian speakers didn't actually mean it that they wanted to win the vote.

It was rather a reaction, a vented irritation over feeling lost and lacking rights.

"This is a matter that, in all likelihood, unified all of the Russian speakers for many reasons [..] The policy of the state is absolutely wrong, [politicians] are ignoring the hopes, needs of the Russian speakers and don't communicate with them at all [..] It was, [among other things] a protest vote. Many were euphoric: 'We've mobilized ourselves around a single idea for the first time'," politics expert Andrei Berdnikov told me on the phone.

But a few are ready to admit that Russians lived through a certain trauma in the 90s, he said. Of course no one here is comparing it to the Stalinist repressions or the russification of Latvia in the Soviet Union.

However, according to Rozenvalds, in 1990s Latvia Russians were treated even harsher than the other Baltic countries. And that's a result of the massive russification during the Soviet era.

Thus the following picture emerges.

The Latvian society and the Latvian state, offended - for understandable reasons - during the Soviet era, starts clamping down on Russians following the restoration of Latvia's independence. In doing so, they offended - for other but also understandable reasons - the national minorities.

Mutual insults pave way to a lack of communication, as well as distrust, voiced intensely by both sides.

I think - and that is evident from my panic before starting to study for the Latvian exam - that pointing fingers and indulging in self-pity doesn't lead to anything constructive. Without noticing it ourselves, in our offences towards a past, which has passed (pun intended), we hurt others and become irritated ourselves.

And here my unwillingness to study Latvian was the last line, the result of all the perceived slights and fear of acting instead of discussing it endlessly in the kitchen.

Having understood all that, I studied for the exam as a normal and conscientious human being.

And I'm glad for that.

* * *

Our next step is taking the naturalization exam, which each of us had tried passing at least once. If we succeed, whole new levels of the naturalization process will open up to us. We'll be reporting about them soon.