I first visited Riga as a tourist, 27 years ago this month, in January 1988. In those days Latvia was still part of the USSR. All flights to Riga went via Leningrad or Moscow, and to get there at all required a Soviet visa.

While still waiting for my visa to be granted, I happened to be having a pleasant drink with a Latvian friend in London when the conversation took an unusual turn. Apropos of nothing, he suddenly said: "Me and a few of the lads are thinking about starting a new Mežabrāļi (Latvian national partisans 1944-58) campaign inside Latvia – what do you think about the idea?"

I understood straight away that anyone who could ask me such a question had to be working for the KGB.

"I think it sounds like a good way of committing suicide," I said, and moved the conversation back to other things. My friend never mentioned the matter again. Soon afterwards my visa was granted.

Born in England, the son of Latvian émigrés who had fled the Soviet occupation of Latvia in 1945, my drinking buddy was a well known and extremely active figure in the Latvian community in London. I first contacted him looking for help translating material on the 1905 revolution and Latvian anarchism. He professed to be an anarchist himself. I knew he had a BA in Russian and Soviet Studies from an English university.

What I didn’t know, until he told me many years later, was that prior to embracing Latvian nationalism he had been a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain.

He has publicly acknowledged his past association with the KGB, and I personally bear him no ill-will. I mention the story only to illustrate how prevalent the KGB was among émigré Latvians. And it is interesting that even in 1988 the KGB were still manipulating the spectre of armed resistance in Latvia to gauge the intentions of foreign tourists like me.

Latvian film director Pēteris Krilovs was a little boy when his father, Osvalds Bileskalns, was arrested and shot by the KGB as a spy in 1951, after being sent back to the Baltic by the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) to operate with the Latvian resistance. In a bizarre twist of fate the first film Krilovs worked on, the 1960s TV series Kad lietus un vēji sitas logā (When rain and wind knock at the window), was a fictionalised depiction of the events linked to his father’s death.

After years of research (including in the archives of KGB interrogations) Krilovs has finally released his own film documentary, Uz spēles Latvija (Latvia at stake).

Set in 1949, the year Krilovs was born, the film focuses on the post war Baltic resistance to Soviet occupation and the games played between the KGB and the intelligence services of Britain, Sweden and America. The film juxtaposes Krilov’s research with animation and scenes from the earlier Soviet melodrama.

The result is not just a powerful human story, but an important historical work – a landmark in Latvian documentary film.

Though a revelation for a Latvian audience, Krilovs’ film owes much to the pioneering research of British author Tom Bower, whose 1989 book The Red Web was based on visits to Latvia and Lithuania in November 1988, where the KGB gave him access to surviving agents of SIS/CIA, and to senior officers of the KGB’s 2nd Chief Directorate (Counter-Intelligence), who were happy to put a fresh spin on old operations as proof of their new policy of “Glasnost”.

In the same spirit of openness I visited Riga again in June 1989, to pursue my research under the sponsorship of the so called “Culture Committee” (Committee for Cultural Relations with Countrymen Abroad - a KGB front organisation).

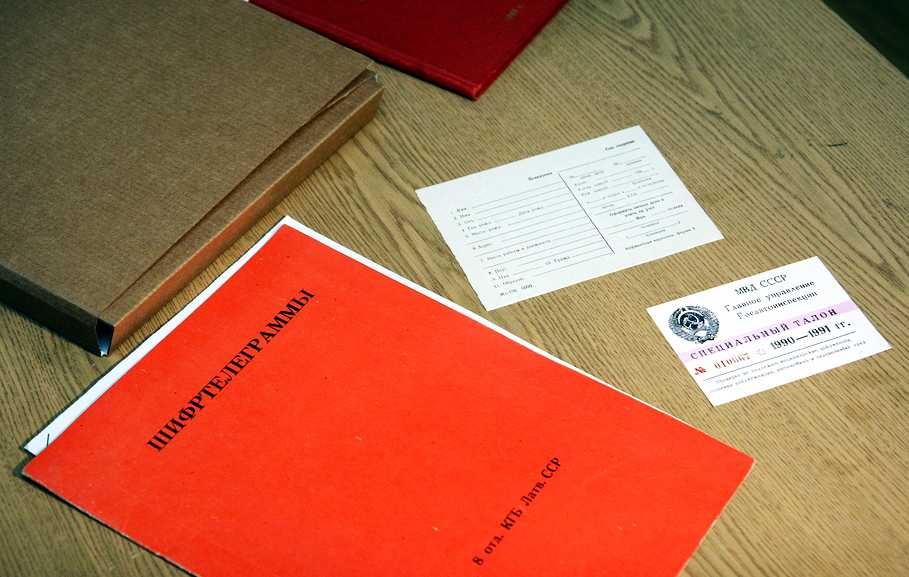

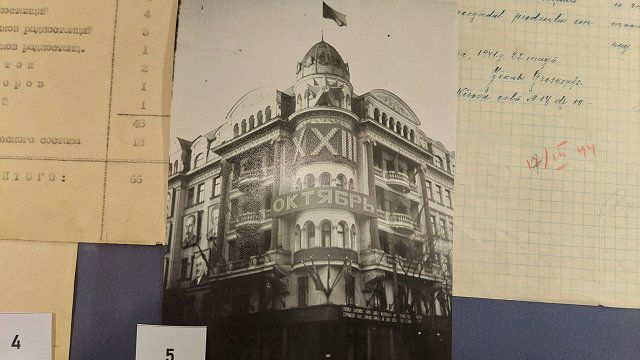

I flabbergasted my hosts by asking for an interview with the KGB. The meeting took place in the notorious Corner House (the building in which Krilovs’ father was interrogated), where I quizzed a young KGB officer about the life of Latvian Chekist Jēkabs Peterss.

The officer I spoke to was eager to impress me with his willingness to engage in serious debate about KGB history by making much of the ways in which they had recently assisted Bower. The officer spoke candidly about how the KGB dealt with those “foreign spies” (like Krilovs’s dad) whom they captured:

‘We made them all the same offer – cooperate with us or you will be shot’.

From the beginning of 1946, all foreign intelligence-backed incursions into the Baltic fell foul of a series of deception operations directed from Riga by KGB General Jānis Lukašēvics, but much of the blame for their failure can be put on Kim Philby, the KGB “mole” inside SIS who defected to Moscow in 1963.

Philby visited Riga only once, in November 1987 (aged 75), and appeared with Lukašēvics on Latvian television, where the pair gleefully denounced Latvian nationalist protests as SIS/CIA inspired. But Philby denied having any involvement with SIS operations in the Baltic after 1947, demurely telling Lukašēvics that he could claim no credit for their failure.

In February 1945 Philby was put in charge of SIS’s anti-Soviet division, which also encompassed (at Philby’s suggestion) all British espionage in USSR.

Among those who worked with Philby was Harry Carr in Stockholm, who ran all SIS operations in the Baltic. In January 1947 Philby was posted to Turkey and officially excluded from further knowledge of Carr’s operations in the Baltic. But in the “clubby” world of SIS Philby would have had plenty of opportunity to fill in any gaps in his operational knowledge – everything he did know went straight to the KGB.

After Philby’s defection to Moscow, Harry Carr was never in any doubt about who was responsible for the failure of his missions. Even senior KGB officers like Yuri Modin and Oleg Kalugin, credit Philby with betraying SIS operations in the Baltic, Ukraine, Belarus, Turkey and Albania.

But the extent of Philby’s role in sabotaging western intelligence operations in the Baltic is academic; by 1947 the KGB really had no need of him.

KGB infiltration and deception operations aimed at the anti-Soviet resistance in the Baltic were total at every level; anyone having contact with or accepting assistance from foreign intelligence services was doomed from the start.

Ironically, the only sections of the Latvian resistance movement who were immune from KGB games were those who found themselves so isolated that they had no foreign connections of any sort and had to rely solely upon their own efforts and resources. There may be a moral there somewhere should Latvians ever be forced to resist Russian imperial ambition again.