A feast in time of plague

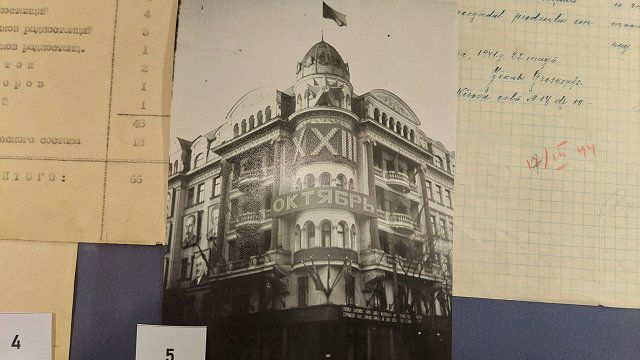

But three weeks earlier, Rīga was celebrating Labor Day, a veritable feast organized by poet Andrejs Upīts. While the Soviet government had almost exhausted its financial resources, it nevertheless was able to find 5 million Rubles to spend on the celebrations. Numerous artworks were set up, the statue of St. Roland in the Town Hall Square was repainted red, and Rīgans were fed with a celebratory soup. There was a fireworks display at the embankment and people were led around on ships decorated according to Soviet taste.

Rīgans – who were famished and ill – had not seen the likes of it for a long time. It was definitely a feast in time of plague.

But Pēteris Stučka, the head of the Soviet government, had to go to Moscow to ask for yet another loan to keep the regime alive. The visit was not entirely successful, as he was asking for 200 million Rubles and granted only 50 million. It was in Moscow that Stučka learned of the fall of Rīga on May 22, 1919.

Stučka's deputy Jūlijs Daniševskis was the man who organized the Red Terror and was de facto leader of the Soviet Latvian Army. He mustered up the courage to call his superior in Moscow only late in the evening. Initially Stučka refused to believe the news, thinking that it's a bad joke and hanging up. Daniševskis had to make a repeat call to really bring home the news to the graying Soviet leader: Red Rīga had fallen.

It was indeed hard to believe, and not only for Stučka. As late as the 30s, the former leader of the Soviet Government and his followers penned many articles and wasted away hours upon hours trying to understand how it could have happened. The mighty Soviet Latvia and its army had collapsed in the blink of an eye, a giant standing on feet of clay.

Political spats delay attack

The anti-Bolshevik forces had spent two months preparing for the attack. In mid-March they had decided to attack Jelgava (Mitau to the Germans) instead of Rīga – one in the hand rather than two in the bush, as the saying goes. And Jelgava was freed March 18. This sparked abject panic at Rīga. Communists, Soviet functionaries, police and soldiers fled the capital. Warehouses and companies were hastily evacuated, and the Soviet government thought about leaving Rīga and moving to Latgale.

But another anti-Bolshevik attack did not follow. German general Rudiger von der Goltz did not want to banish Stučka from Rīga only for Kārlis Ulmanis to take his place. The attack on Rīga was postponed, and the "Liepāja putsch" took place. Kārlis Ulmanis' government was toppled and after prolonged political squabbles pastor Andrievs Niedra – who learned about this post factum – was named the new Prime Minister.

At the time, Niedra was trying to cross the front line, wading and meandering through Tīreļpurvs swamp near Rīga. He did find his way out, but started bogging down the entire of Latvia after becoming the head of state. His main promise was freeing Rīga from the Bolsheviks, and he said it was his only motive for accepting the post of PM.

But after Rīga was freed it turned out the pastor was not entirely true to his word. From a self-sacrificing hero figure on a historic quest, he quickly became a hated traitor, or what would later be known as a Quisling.

Freeing Rīga was indeed a historic task on a Latvian, Baltic and European scale. Representatives of the UK, France and the US knew it well. Ulmanis, whose government was exiled to a steamboat in Liepāja, knew it too. The Americans promised to nourish the starving Rīgans, sending a train with food even before the order to attack had been given. Ulmanis led formal talks with Niedra over setting up a compromise government. Niedra freed several officers and politicians who had been arrested. Colonel Jānis Balodis and Russian prince Anatol von Lieven refused to get involved in politics, subordinating their interests to the shared goal of freeing Rīga.

Attack comes as a surprise

In May 1919, the front line stretched south from the Gulf of Rīga on the bank of the River Lielupe to Jelgava and then to Bauska. Rīga was about 40 km away. Back then, armies needed two days to cover such a distance. But in this case there was a swamp ahead, and the broad River Daugava, and an enemy that had an equal strength in numbers. The anti-Bolshevik forces did not have the machinery to force a crossing over a river the width of the Daugava. Therefore, in order to take Rīga, they had to occupy the bridges. And if they didn't want the communists killing hundreds of hostages held in the capital's prisons, the bridges had to be occupied within the span of a few hours. A task like this, given the way war was waged back then, seemed almost impossible to accomplish, and it seemed to be a miracle when it finally was.

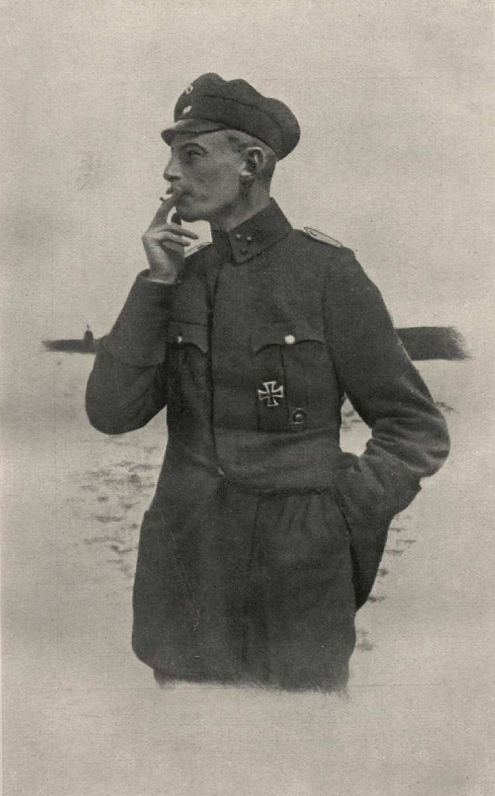

The attackers' forces were concentrated into three columns. The brigade under Jānis Balodis had to attack from the north, through the Jūrmala town. A mixed column of Baltic Germans, Latvians and Russians attacked from the foothold of Kalnciems – the most direct way to Rīga. The third column, led by commander of the pro-German Baltische Landeswehr Alfred Fletcher, attacked through the most complex and risky route, through the aforementioned Tīreļpurvs. This column too had several Latvian units.

On the night of May 22, anti-Bolshevik forces were able to surprise the Reds utterly. The Soviet headquarters quickly lost their hold on the events, while the soldiers – under-dressed, under-trained, and under-armed – were not particularly eager to fight, instead preferring to retreat or become POWs.

Particularly successful was the attack through Tīreļpurvs. At 1 p.m. the avant-garde of the Baltic German forces reached the Zasulauks–Šampēteris neighborhoods. Two kilometers away from Torņakalns the German Baron Hans von Manteuffel caught up with the avant-garde and assumed its lead, storming across the Lubeck wooden bridge on the River Daugava (it was situated about where the current Stone Bridge stands now). After 30 minutes, the tiny forces of the Landeswehr reached the bridge where they faced off with the cadets of the Soviet Institute of War. They had just stepped on the bridge to go help the defenders of the left bank, called Pārdaugava. They were dispersed with machine gun fire and many of them fell. A small group of Baltic German Home Guards crossed the bridge to go to the Citadel Prison to free the hostages held there. While the operation was successful, Von Manteuffel fell in the ensuing skirmishes near the prison. But the prisoners at Centrālcietums (Central Prison) met a grave fate.

As the communists learned of the attack, they drove 32 prisoners – including highly esteemed Baltic German pastors – into the courtyard where they were bayoneted and blasted with grenades.

Skirmishes in the streets of Rīga

From the memories of communist fighter Alma Pesa

Hiding behind the bridge railings, we fought back while retreating slowly. As we had retreated to Dzirnavu Street, there was real shooting. Hiding behind a monument, the enemy shot at us while us, as we were ducking behind corners of Dzirnavu and Aleksandra Street, were shooting against anyone who popped their head.

I can't say for sure whether we hit someone, but as I released my final shot my head started veering towards one side. I wanted to look at something but I felt pressure on my shoulder. A stream of blood was trickling near my blouse. I was promptly undressed and they started bandaging me. A puddle of blood remained on the pavement. [...] [At another bandaging point] the young field doctor kissed my hand, put me in a carriage and told the driver to take me to the Ropaži station where there's a train of the Red Cross. Near the Ropaži station I saw a couple of our female comrades, who had guns. There was Andrejs Upītis there, while Emīlija Krustiņsone had sat down with Elga on her lap and a gun on her side. As I looked upon this, I thought that all the sorrows of the world had settled in her face.

I became feverish, my teeth were rattling. I was placed in a bed in the Red Cross train car. They wanted to take my gun away but I put it beside me. I was suffering greatly but not physically. It was rather moral pain. I felt sorrow for Rīga. It pained me not knowing where all my comrades, and others, are. I wanted to cry but revolutionaries aren't supposed to cry.

Fierce fighting continued in central Rīga late into the afternoon. There were thousands of police and armed workers in the city, and a part of them partook in defending the city. They were poorly trained and badly managed, incurring great losses in the fight. There were many women among them, the so-called plintnieces (from plinte, a gun) who had earned an unenviable reputation during the Soviet occupation.

But not all workers were dedicated to what was supposedly their cause. During the fights, locals were shooting at the soldiers of the Red Army from their windows and even threw flowerpots on their heads. After the Second World War, the Soviet propaganda would honor the heroes who died fighting. Among them was Nikolajs Allens, Deputy Employment Commisar. But eyewitnesses said that this honorable Soviet functionary died trying to leave the Employment Commisariat holding an expensive Persian rug. Someone shot him from around the corner of a building. Allens' rug was not the only thing that the liberators of Rīga got their hands on. They also seized the funds of the State Treasury, State Bank, along with stores of food, a train as well as several thousand POWs.

Fighting continued in Rīga's outskirts until early May 23 when the final units of the Reds retreated to Jugla. At the same time, Jānis Balodis' Latvian brigades arrived in Rīga from the other side. These had spent the night in the outskirts.

Later on Balodis would find fault with Alfred Fletcher saying he hadn't allowed the Latvians to enter Rīga on May 22. But this wasn't strictly true as Balodis' brigade was slow to attack. At the time when the Baltic German avant-garde was crossing the Lubeck bridge, Balodis' forces had only reached Piņķi.

Be that as it may, the successful attack on Rīga was in many ways a lucky break for the Baltic Germans in particular - and perhaps a reason why they soon after pushed their luck a bit too far. But their fighting ability was beyond question and they nevertheless lost some of their best officers on the bridges and in Old Rīga. Prince Lieven was likewise heavily wounded on May 24 near Ropaži while pursuing the enemy.

Conflicting memories

After the end of the Latvian Independence War, May 22 became the biggest celebration for the Baltic German population, it was basically a Victory Day for them. But the Latvians and especially Latvian social democrats were more ambivalent about the date, saying that the victors were brutal against the defeated. They said the Red Terror was lifted only to give way to White Terror, claiming some four to seven thousand people were killed after Rīga was freed. But Allied representatives said the number was 500.

The disputes intensified in the following years, and in 1929 unknown perpetrators blew up the central obelisk of the Landeswehr cemetery.

But before the outbreak of the Second World War, it seemed that a compromise had finally been reached. The 20th anniversary of liberating Rīga was observed with splendor, and high-ranking officials including now-dictator Kārlis Ulmanis participated alongside Alfred Fletcher and other veterans of the war.

Even as the Baltic Germans left for their Heimat, willingly or otherwise, they continued observing May 22 as a day of victory against communism.

Indeed, May 22 was a clear-cut historical victory in which the Latvian population, divided ethnically and politically, united its forces for the greater goal of ending the Red Terror.