The merits of the Baltic German lawyer, political scientist and historian with Latvian citizenship are extensive.

When almost all participants of a half a day long conference dedicated to the life and work a single person have difficulty in finishing their speeches on time and even need to shorten them while speaking, it clearly indicates that the achievements of the person in question have been vast.

In the case of Dietrich André Loeber this might be even a massive understatement. The Baltic German lawyer, political scientist and historian played a crucial role in re-establishing Latvia as a law-governed state and reintroducing an independent and fully-functioning legal system after the country regained its independence in 1991.

Before that, he actively supported Latvia’s quest for freedom and tirelessly reminded the world about the Soviet occupation of the Baltic States in and legal periodicals published in the West.

“Latvia appreciates Professor Loeber's contribution to the good of our country and will always be grateful for his devotion to his homeland,“ President Egils Levits stated in his speech at the centenary conference for Loeber on January 4.

“During the long years of occupation, Loeber did not lose faith that justice would prevail and that Latvia would be free and independent again, and he did everything possible to achieve this“, the head of state said, adding that Loeber has made a "lasting contribution" to Latvian law and the restoration of Latvia's independence from the Soviet Union.

Similar evaluations were also given by other speakers that provided extensive assessments of Loeber’s work in the legal field and beyond. What also became clear is that many of them – including Levits – considered Loeber not only to have been an academic colleague but also a dear friend and unforgettable person who could be relied on in any situation.

Among the participants of the events were also representatives of the Loeber family that gave some personal insight into family life but also discovered for themselves some yet unknown aspects during the course of the half-day long conference.

"When you suddenly hear all sorts of things about your own father from third parties, and some of it I don't even know, then you think: ’Oh, that was really something special.’ Because he didn't brag about it at home at all“, Alexis Loeber, the eldest of Dietrich Loeber’s four children, told LSM. "You only hear these things now from people who knew and valued him. This is a good feeling.“

Born in Latvia, educated in Germany, at home around the world, Loeber was born a century ago in Riga on 4 January 1923 as son of a high-ranking judge in the then independent Republic of Latvia but in 1939 with his family – like the other Baltic Germans – was forced to leave his homeland. Following the pact between the dictators Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin, the Baltics came into the sphere of Soviet influence and the young Dietrich and his parents were called “back home to the Reich” and deprived of their Latvian citizenship.

Ending up in Germany after World War II, Loeber studied law in Marburg and continued his legal education at foreign universities in an academic career that was truly multidisciplinary and international – with many scholarly and research activities and an impressive list in scientific publications.

Specialising in Soviet law and the legal system of the communist world, the early 1960s saw Loeber’s first professional appointment in the USA that was followed by visiting professorships at prestigious academic institutions such as Harvard Law School, University of California, Stanford University or Columbia University.

Research and lecture activities have also taken him to long-term study visits at the Moscow Lomonosov University or the Russian Academy of Sciences. Other guest professorships took the much sought-after lecturer as far as Australia. In total, Loeber worked and lectured on three continents in four languages, all of which he spoke about equally well: German, English, Russian and Latvian.

Reflecting his birth and early years in Rīga, Loeber also took a special interest in legal questions involving the Baltic States and has published an large volume of writings on the subject. The highlight of his efforts was been a book about the resettlement of the Baltic Germans from Estonia and Latvia for which Loeber coined the still widely used term “dictated option”. Likewise, scholars have also for decades quoted other major writings of the inventive and resourceful researcher who had a special interest in the interaction between law and politics.

KGB supervision and the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

Loeber was one of the first Baltic Germans to visit the Soviet Republic of Latvia after the war in 1961 and was also one of the first foreign citizens that were issued an entry visa to the Republic of Latvia at Riga airport on 28 August 1991.

"I have been here as visitor several times, but today is a historic day," Loeber back then told the Latvian daily Diena. His close relationship to his home country was also confirmed by his Latvian citizen's passport, which was issued to him by the Latvian Embassy in London in mid-1954 after Loeber applied for it.

The historic episode and legally significant decision to reinstate the Latvian citizenship withdrawn from him in 1939 provided later also Loeber’s children the right to Latvian citizenship – in accordance with the doctrine of the continuity of the state. But this was only recognized in a 2018 landmark judgement of the Supreme Court that is considered to be one of the most important in the field of national law in contemporary Latvia, according to the law periodical Jurista Vārds.

Loeber's frequent visits to his homeland during the Soviet period naturally attracted the attention of the KGB, which constantly monitored and observed him, closely following all his movements. His files were one of the few that were completely preserved in Latvia. From there, it emerges that the KGB suspected him to be a German spy and of having connections with the special services of Western countries. Loeber later got acquainted with the 800 pages of documents collected by the KGB about him and published his findings in 1996 in the magazine Latvijas arhīvi.

Whether there are also such comprehensive KGB files about Loeber in Estonia is not known. But what is sure is that there was much to write about him there as well, especially about his daredevil actions in the autumn of 1988 and 1989 when Loeber at scientific conferences in Tallinn talked publicly about the notorious Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and its secret protocols, which at that time were still officially denied by the Soviet Union. The agreement between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union cleared the way for Moscow to annex the Baltic states in 1940. The printed documentation of a facsimile edition of the secrets protocols from German archives that Loeber had brought with him in numerous copies were snatched from his hands and eagerly studied by the participants.

“The lecture was interesting too. But for the first time we saw a coloured copy of this famous map, on which Stalin and Hitler with their signatures divided up Europe“, the Estonian legal scholar and historian Peeter Järvelaid remembered about the historic conference, praising Loeber’s courage, foresight and perfect timing to publicly discuss the secret protocols.

The bold move set in motion a series of events, due to which at the end of 1989 the Congress of People's Deputies of the Soviet Union recognized that the pact existed and that it was invalid.

Shaping Latvian law and lawyers

Starting out the anniversary day in the morning at the memorial plaque for Loeber at his birthplace in Hospitalu iela, President Levits also dived into his own past and personal relationship with the renowned scholar who has received the highest state awards in both Latvia and Estonia.

In very personal notes, the Latvian President remembered Loeber as a “special friend” and his academic teacher, for whom he worked as a scientific assistant at the University of Kiel in the mid-1980s.

"The professional and personal connection between us was very strong," Levits said, adding that in 1975 he was accepted into the Latvian student corporation Fraternitas Lataviensis in Loeber's house in Hamburg.

Yet not only the former judge Levits, who spent part of his early life in Germany, but also other high-level Latvian legal experts were able to benefit from the wide knowledge and expertise of Loeber who continued to hold lectures in both Rīga and in Tartu after the Baltic States regained their independence in 1991.

Under his auspices, a foundation and scholarships were established for supporting talented young lawyers, and the honorary doctorate degree of the University of Latvia personally financed a number of books and collections of legal articles.

“He was the first to introduce me to EU law – and today that is my job“, the current Latvian Judge of the Court of the European Union (EU), Ineta Ziemele, remembered her time as student at the beginning of the 1990s when she was visiting the first-ever courses in European Law in Latvia read by Loeber at the University of Latvia.

"We were a rather large group who had the unique opportunity to attend his lectures and enthusiastically went to them,“ she said.

Loeber contributed also to the translation of the founding treaties of the European Community into Latvian and previously also set many fundamentals in other law fields in Latvia, especially during the crucial transformation of the legal system from the Soviet idea of law to Western standards. To the first World Congress of Latvian Lawyers, which took place in Riga in October 1990, the law specialist brought along with him a self-published version of the Latvian Civil Code of 1937 that later was restored and renewed. Loeber also participated in elaborating legal provisions and in another being-the-first-to-do-so-event prepared the first-ever issued commentary on the Latvian Constitution after its adoption.

Roots and homecomings

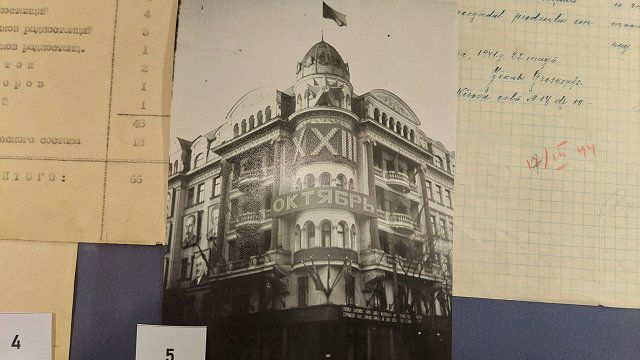

Loeber also helped also to republish the rulings of the Senate of the Republic of Latvia and was the first to encourage studying the jurisprudence of the interwar period to develop legal practice in Latvia and achieve legal certainty. His interest in the work of the Senate derived from his very own personal interest since his father August Loeber (1865-1948) was one of the first senators of the Senate of Latvia – the highest court instance of the 1918 Republic. Loeber senior served from 1918 until 1938 and is considered to be one of founding fathers of Latvian court system and the Latvian civil law. His legacy is also remembered in the rather unknown Supreme Court Museum that was established in 1998 by material donations and financial support of Loeber junior.

Another museum in Riga closely connected to his name is the Mentzendorff House which used to belong to his mother’s family and in which he had lifelong residency rights. Dietrich Loeber was the grandson of the last pre-war house owner, August Mentzendorff, and considered the well-preserved historic building just a couple dozen meters from the Town Hall Square to be his second place of residence. Restored in 1992, the Mentzendorff House now houses a museum and the Latvian Baltic-German culture association Domus Rigensis that was established upon the initiative of Loeber and others. On the top floor there is also memorial bureau where Loeber’s former desk and other personal belongings are on display.

Celebrating the 100th anniversary at another memorial get-together in the Mentzendorff House after the academic conference, many companions and personal acquaintances of Loeber described him as a selfless, generous philanthropist.

“In the end, Professor Loeber was – and that is the most important thing for me – simply a human being”, Domus Rigensis board member Philipp Schwartz pointed out. “He was an open, accessible, interested person who showed how important and how easy it is to cross borders – geographical, spiritual, linguistic, cultural borders – if you only want to do so."