In the shadow of a peace agreement

The ink had not yet dried on the Brest-Litovsk treaty, and governments had yet to ratify it. Nevertheless, the Germans already assumed the task of politically rebuilding their newly acquired territories. Russia had conceded the former Courland Governorate, and Germany had to decide what to do with it.

Nevertheless, that Russia did not want it was not enough. To become a truly legitimate body, it had to have local support (in this case, from the local Baltic Germans) voiced through their "will".

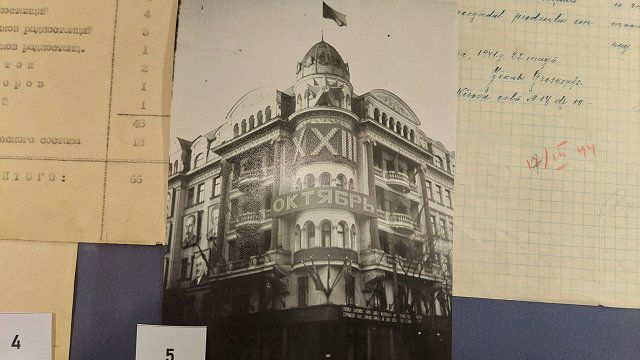

There was also a short-lived wartime state existing from 8 March to 22 September 1918 with the same name. Plans for it to become part of the United Baltic Duchy, subject to the German Empire, were thwarted by Germany's surrender of the Baltic region at the end of the First World War. The area became a part of Latvia at the end of World War I; see Duchy of Courland and Semigallia (1918).

Dilemma

On the one hand, local Baltic Germans wanted to establish close ties between Courland and Germany, and to prevent the establishment of democratic institutions in order to retain the privilege they had been enjoying.

On the other hand, the German parliament and democratic forces in that country were opposed to annexing territories in the East, insisting upon the principle of self-determination.

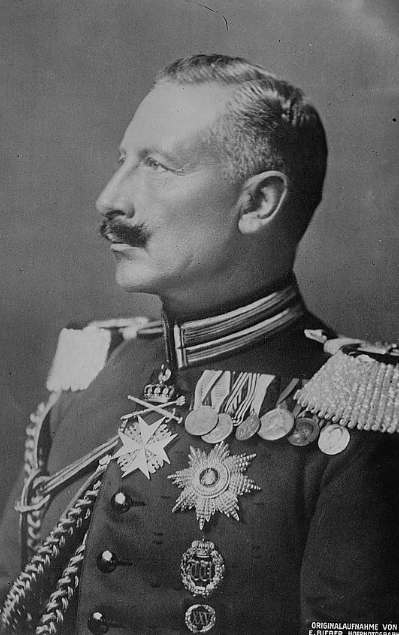

German Emperor Wilhelm II, the German military and the local governments of the occupied territories had different opinions about the future of the territories they had subdued, changing with the political ideas and the success they were enjoying at the Western front at any given time.

A free and independent state

The March 8 Kurländischer Landtag (state diet) - took place in an euphoric atmosphere. Russia had been brought to its knees. It seemed that France would be beaten within the next few months too. The meeting was opened by Alfred von Goßler, the head of Courland's Ober Ost.

The Landtag adopted a plea by nine Germans (including several barons and Baltic-German socialites) and a single Latvian (local parish master Augusts Vēžnieks) that asked the German "Kaiser and Emperor to majestically accept to assume the crown of the Duke of Courland for himself and his descendants".

On March 15 Wilhelm II proclaimed the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia a "free and sovereign state", but did not assume the title of the Duke of Courland.

Resonance

There was no question as to whether allow the co-existence of two states within German-controlled territories. This was discouraged by Russian experience and the shamelessness on the part of several Baltic-German barons who, after the Duchy was declared independent, asked the head of the Ober Ost to cover the expenses caused by the occupation of Kurzeme.

Latvian politicians were ambiguous about the Baltic Germans' initiatives. The Latvian Provisional National Council and other nationally- and democratically-minded organizations in Russia and abroad condemned the attempts to set up state-like bodies that would have been German puppets in Latvia.

Nevertheless others, who assumed Germany would win the war, thought they must do what they can to rescue the Latvian people from complete annihilation. They were ready to discuss Baltic-German initiatives and draw their signatures on different documents.

These included the aforementioned Vēžnieks, as well as Frīdrihs Veinbergs, Andrejs Krastkalns, Konstantīns Pēkšens, Jānis Brigaders, and other notable Latvians.

In return, they asked Latvia's territory to be united into a single body, and guarantees for protecting the Latvian language and culture; and to prevent the arrival of German colonists.