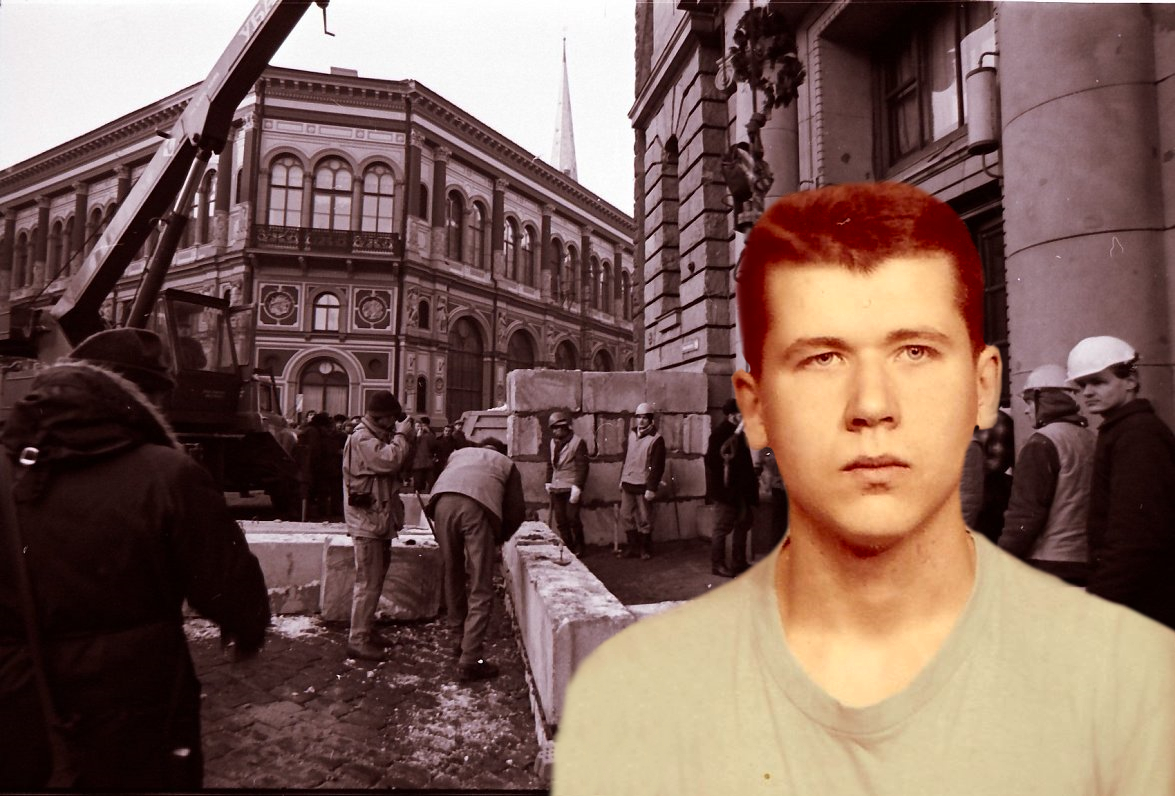

IT specialist Jānis Blūms was fifteen at the time of the barricades event. He was surprisingly well-read for his age, and happened to be near the Interior Ministry. He remembers the events well and spoke to LSM on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of the event.

Where did you live and what did you do at the time of the barricades?

I was fifteen and living right here in Mežaparks. I was lucky back then. I was interested in religion, as a teenager. We had an impromptu group which came together, initially at an Ausekļa street apartment. There were many interesting people there, intellectuals, and we talked. And later on we held meetings at the Anglican Church. At the evening of the notorious shootout at the Interior Ministry, I happened to be at St. Gertrude's Church.

Timeline of the barricades (1991)

January 1 - OMON special forces take over the Press House

January 10 - Pro-Soviet Interfront calls on Latvian government to resign

January 12 - Mikhail Gorbachev promises armed forces won't be used in Rīga

January 13 - Soviet tanks attack Lithuanian TV, radio, telegraph, killing 14

January 13 - National awakening figure Dainis Īvāns calls people to flock to Doma square to build barricades

January 13 - The Pan-Latvian Manifestation of some 500,000 takes place by the Daugava river

January 16 - Roberts Mūrnieks is shot by the Mangaļu bridge

January 20 - 100,000 gather in Moscow to express their support for the Baltics

January 20 - OMON attacks the Interior Ministry, killing five people, including two camera operators and a schoolboy

January 21 - Gorbunovs goes to Moscow to hold talks with Gorbachev

January 25 - Funeral of the victims. Most of the participants head home.

Upon exiting the church, I heard a noise that didn't sound like a shootout at first, but I was drawn to go and have a look at what's happening there. I walked down Brīvības Street to the [hotel] Latvija. There was a bus burning. Then it became clear there was shooting, you could see tracer ammunition flying. I called my parents and asked them, "Do you know what's happening?" The TV building hadn't been stormed at the time, and so there was information circulating.

I remember that I was at the Doma Square back then with a rather extravagant look, sporting a faux leather jacket. People dressed quite hip back then. I don't know how many times I was there and why my parents let me go, perhaps because my sister was doing rounds at the Rīga Cathedral medical point. I remember the time well, and what I felt back then.

Did your family talk to you, a teenager, about the occupation of Latvia?

Of course. Before that, mom and I partook in the Baltic Way. There were several demonstrations, including the big event at the Mežaparks open-air stage. I recall us going to the embankment to protest as well. The [national] Awakening had started beforehand, there had been talk of it for several years. I was old enough to understand what's going on.

What was your understanding and outlook on what happened during the barricades?

The way I looked at it, it was a poker game and we were going all-in. The whole independence thing was hanging by a thread. We could have soldiers arrive with BMPs and destroy the whole thing. But we had a feeling it wouldn't happen, as there were too many of us there.

As I was preparing for the interview, I recalled in retrospect that there were many Russians going to the barricades too. It was a moment when the opposition between "us, the Latvians" and "them, the Russians" disappeared. There were many Russians there and we understood that they are our own kind. What I also find interesting is that it was a time of leadership. We had pronounced leaders, such as [Marina] Kostaņecka, [Dainis] Īvāns, [Ojārs] Rubenis, [Valdis] Šteins, [Sarmīte] Ēlerte, [Mavriks] Vulfsons and others. Perhaps it was all propelled because we had a black-and-white game back then. We want independence, we are the white ones. The goal we shared was so evident that the battle was very clear. Before, and after, Latvians and Russians split off again. We are the Latvians, the core of the nation, and they are the Russians. The topic is not that current anymore, but it's still in the background, it hasn't been solved. I mean we still feel as if Russians posed a threat. There's a bitterness. But then I felt that we were together.

Uldis Pētersons, the director of the Talsi National Museum, noted in an interview that looking back at the events sparks a strange feeling. People of different nationalities went to the barricades, but part of the people who fought for Latvian independence were then "screwed over" by the newly-founded state.

Well, yes, the non-citizen status was instated, and so on, and it's still continuing. They feel as if they're non-citizens, while we feel them to be the descendants of occupants who haven't burdened themselves with learning Latvian throughout their lives. This criticism is not unfair, as the unwillingness on the part of the big nation to learn Latvian is vexingly palpable. Perhaps the younger generation doesn't look at it that way, but the older one does. We feel the Russian language to be a threat, but this is completely normal, and it is justifiable. But that's a whole other story.

What else do you remember about January 1991?

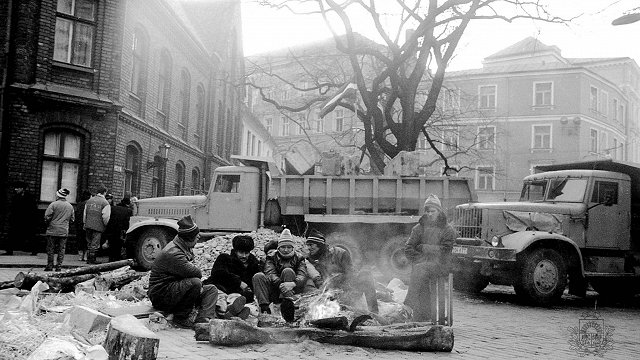

I remember barricades in Rīga. There was something on Dzirnavu Street, near Lattelecom. There were heavy trucks there. Of course, I recall the Cabinet of Ministers and Doma Square. I wasn't present at Zaķusala, I don't remember it. I recall the interview with video operator Juris Podnieks. He said he had used a bullet-pierced Lada car to carry videos from Lithuania. Things were more tragic in Lithuania. I was well-informed, but as for the shootings I was there only for the ones in Old Rīga.

Weren't you afraid?

Well... At the Hotel Latvija it was evident that the bullets weren't fired towards us. It was a block away in the direction of Raiņa boulevard. I didn't go any further, as it was clear that big things are happening there. Of course, I was afraid and I was there only for a little while. As for the barricades and the Doma Square, I wasn't afraid there as people were rather relaxed, assuming an attitude of waiting.

There was the media, the radio. The fact that there were international reports sent out gave us peace of mind. There were representatives, I think, from CNN.

Perhaps this did the trick. They just wouldn't dare.

Do you recall how the barricades came to a close and what happened in August?

I think the barricades lasted little short of a month. I don't know what the orders were, but at one point it became clear there'd be no further escalation, that the moment had been lost, they had not reacted at the time and now it was too late. Then they simply went back to their bases and we wouldn't get a whiff of them. Half a year later, it was August. There was a coup in Moscow, the military took over the [Baltic matter], thinking that they'd solve it as men would, using force. When [Boris] Pugo shot himself, it was clear the party's over. Well, of course, [Alfrēds] Rubiks would forever stay the same, but the dark time stopped after August. [..]

Did the events of January and August change your life? Did you feel any changes?

We had regained our independence. Theoretically, we had gotten what we wanted. The next thing we wanted was to bring our quality of life up to par with the West. Business games, business ethics, the dark times of the 1990s started, Rumbula, the shashliks.

It was an era when people tried earning as much money as quickly as possible. The Banka Baltija offered enormous interest rates, something unreal and hypertrophied. We wanted to catch up with the West forgetting about preparatory work we have to do.

We are still doing preparatory work, such as arranging the legal system, education and so forth. In truth, a lot has been done, but, on the other hand, we haven't grown as much as we wanted to as a nation and as a people. We spent a lot of time messing around with matters related to corruption, and it's still present. Perhaps every state has gone through this, as truth be told thirty years is not a long time. My life didn't change much. In 1994 I graduated high school and started working, it was three years after the barricades, and started my grown-up life. I am happy to have experienced it all first-hand. A feeling for the Soviet times. The Awakening and the current events. I was in a very good position to experience it all. It was lost for the generation that came after me.

But children will be taught this at school.

Of course, on the level of facts they will study all of it, but on the level of feeling, when you're in medias res... I am rather amazed at how the parents were able to deal with all of this at the time. Okay, we had the countryside, we planted potatoes and so forth. But in the early 1990s were extremely difficult in terms of everyday life. I didn't feel it as much, my needs were much smaller, everything was beautiful and nice, but I'm unsure if everyone felt that way. There was the change of currency. There was the Latvian Rouble, then the "repšiki" currency and then these were exchanged to lats at a rate of 1 for 200. Many people had it pretty hard.

It seems that many lives were broken with the move away from a command economy. Those of factory workers, for example, as well as engineers that had been educated and brought up to serve the Soviet system. Did your parents change their job as well?

My parents have always been innovative when it comes to survival. In the Soviet era, they would grow tulips for sale one year and sell gingerbread cookies the next. We were all busy doing that, we bought a Lada for the money. They made amber jewelry, we grew pumpkins... The opportunities were there. I assume that it was a lot more difficult for those working at factories. I do not have an idea. I can simply surmise they had it rather difficult.

What's your current take on the meaning of the barricades and the way we've come?

It was definitely a turning point, with the clock chiming a round hour. It was our de facto, the moment we regain our freedom, with all of us present. The ones who were there will never forget it. Where are we now? I am somewhat saddened by many things, but I think we have to give it time. We have a good country. I like it. I would have wanted us to leave the old ways of thinking behind faster, to leave behind the old cadres, the old, Dūklavs-style politics.

I am still worried about the fact there are lame surprises every election. Populism is on the rise, we have Gobzems- and Kaimiņš-like people who can still lure the people despite all the experience they have. I think we should have more understanding about our true values. Right now, there's a large percentage of people that are.... stupid, pardon my French. And their number isn't decreasing. I'm afraid that it won't decrease in time. I see small groups partaking in elections, people who can't make their snowball bigger via unification.

As for the state as such, I think it's good. Perhaps I've been in luck regarding my career.

There are things that still haven't been solved. Retirement benefits are one example. Pensioners didn't live well before and they're still living badly with very small benefits. Or education – if we had invested into it earlier, our returns would have come earlier and would have been bigger. I didn't mention the EU. I think that it's a very big boon to have access to funds and invest the money before all the crises. Crises are a setback, but despite that we still have the infrastructure, we have roads and bridges. It's a big thing. If we didn't have that, it'd be bad. But the funds will run out sometime, and we will be on our own. We have to prepare for that.

Do I understand you correctly? Do you think we aren't looking forward as much as we should right now?

Yes. Again, concerning the election. We are still stepping on the same rake. There are no indications this will change. Earlier people were wooed by Ziedonis Čevers' parties. Now we have our own sort of populism. There's a lack of a clear vision. I would like us to be more pragmatic and more discerning.