The Cesis bus stop caught my eye for the simple reason that instead of an advertisement for a cellphone company, an ice-cream company or a fuel company engaged in a catastrophic re-branding effort, the bus stop displayed art: and not even of the graffiti variety. It displayed a painting by the great Norwegian artist Edvard Munch and the slogan - so restrained as to be almost invisible - 'Munch meets Rothko in Daugavpils'.

This was immediately appealing. I had heard that thanks to a cooperation project between the Trondheim Kunstmuseum and the Mark Rothko Art Center in Daugavpils, a Munch painting was on loan for the summer, but I hadn't really taken much notice of the specific artwork in question. Now it was reproduced on this bus stop in Cesis and I was able to look at it. It was a man standing, holding a top hat and cane, looking fairly sad.

It was in the completely unsensational, downbeat, understated nature of the image and slogan combined that I took pleasure. In the era of the must-see, book-ahead, headline-grabbing, pop-art, giftshop-friendly, buy-the-T-shirt art exhibitions that fill the Tate, the Pompidou and the Guggenheim season after season, the whispered hint that a single painting by Munch was on show at the other end of the country seemed not only adult but - one might even say - 'noble'.

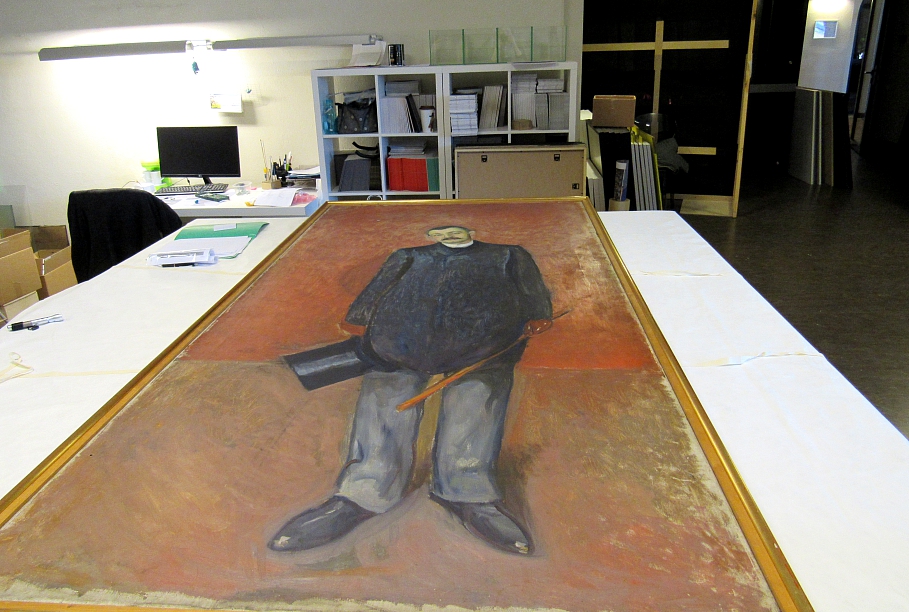

I resolved to go to Daugavpils with a single goal: to sit all day with Portrait of Advocate Ludvig Meyer (fragment/oil on canvas/200x100cm/1909).

At this point I should say I am not some sort of Munch nut who was immediately thrown into a frenzy at the prospect of seeing the brushwork of my hero. I believe I had one of his pictures tacked to my wall amongst many others when I was a student (not The Scream, I hasten to add. It was something much nastier). I have often encountered him on the covers of books by Strindberg and other Scandinavian writers with unimaginative publishers. And this is what made the experiment worthwhile: it would be very inconvenient and reasonably expensive to get to Daugavpils just to see one painting. In a way, it was a waste of time and money. But perhaps the quality of this single painting would be such that it would still be worth it?

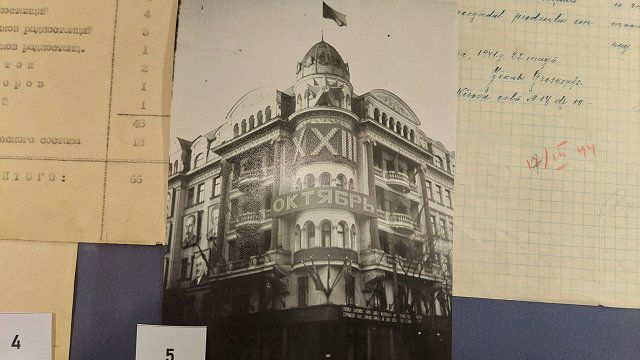

Two days and 250 kilometers of roads - some of them gravel - later, I arrived at the Mark Rothko Art Center, located in a vast Tsarist-era fortress on the banks of the River Daugava. It had taken four hours and half a tank of diesel to get there. I have been there a few times before: first when the fortress was still a complete wreck, ten years ago, then when the art center opened, and a couple of times since. The transformation continues to astound, yet still feels as if it has only just begun. But I was not here to admire the restoration work. I was here to meet Ludvig.

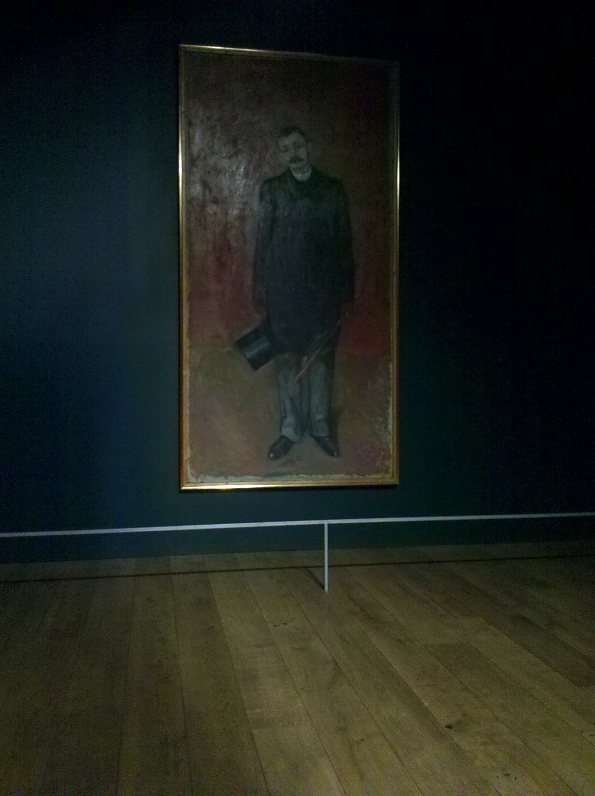

The image on the Cesis bus stop had been roughly half the actual size of the painting. There beside the entrance to the museum was a huge banner of Ludvig. It made him look imposing, even intimidating. I suddenly felt a bit apprehensive, the way one does before meeting some important political or religious leader. It's partly a sense of unpreparedness, partly a fear that one might just be immensely disappointed an unable to hide the fact.

I bought a ticket. It seemed a quiet time in the galleries. A guide was keen to show me around, and not surprisingly, keen to talk about the life and works of Mark Rothko, who was born in Daugavpils. I felt a bit of a heel telling him: "Thanks, but I just want to spend a few hours with the Munch painting."

I am not an art critic. I had some vague ideas about what sort of feature I might be able to write as a result of this visit. Presumably it would be something attesting to the power of art and the humanity of Munch's vision. Things about mortality always go down well because they don't mean much and it is perfectly obvious we are all going to die, so no-one can argue if you draw that as your conclusion. I envisaged a cheesy final line that would be something like: "...and as I left I was sure that I could just see a wry little grin from beneath that droopy moustache!" That's the sort of thing editors and advertisers love.

However, that was not what happened. So rather than work the notes I made over the course of a couple of hours secluded with Ludvig Meyer into any more overblown prose, I have decided simply to reproduce them below.

THE PICTURE - precisely life size and full length, but because it is hung on the wall instead of resting on the floor, he appears to be levitating.

COAT - made up of vertical broad strokes, like feathers. With his head cocked to one side he looks like nothing so much as a bedraggled raven. All the work is in the coat and the face. The face is the only soft piece of painting. The closer you get to him, the sadder he becomes. From a distance, and certainly in the reproductions, he looks a bit dopey. But ''in the flesh" he is much more sympathetic. Were it not for the top hat and cane, one might take him for a priest.

THE BACKGROUND - a ''wall'' of dark red and a ''floor'' of paler red could actually be taken for a Rothko if one removed Ludvig from the picture. His hands, in red leather gloves, are almost invisible. There is something infernal about it. Hell as a barren desert. A Martian landscape. A limp, black flame in an empty hell. A dried-up, boring treadmill of a hell.

THE CANE is enigmatic. It is held quite limply, yet is held a third of the way down rather than at the end. Suggests it might be raised to strike - though the tired and passive face of Ludvig makes this almost unimaginable. The top hat and cane seem incredibly heavy, as if he can barely hold them. Slumped shoulders. Props. Maintaining semblance of social and legal roles. Incredible tiredness. Exhaustion. A man who is completely used up. Dressed for his own funeral.

THE LITTLE ROOM in which he is exhibited only adds to the impression that this is a side-chapel in a large cathedral or perhaps a priest's or prisoner's cell.

AT FIRST GLANCE it seems an insipid picture. An unfinished thing, perhaps a portrait dashed off to make some quick money. After a while it becomes unbearably tragic. The face is the only thing rendered in detail and sharply, which forces the viewer to look at it and in particular those sad eyes. Munch has built up layers of paint on the forehead and cheeks to give the impression of living flesh and prevent the cadaverousness of some of his other works. It is just enough to establish that this man is still alive. His sadness is unending. Poor Ludvig.

During the course of this meeting between Ludvig and myself, only one other person came into the partitioned cubicle. She looked at him from the left, then the right, said something in Russian to an unseen companion who had not come into the cubicle and exited. I'm not even sure she saw me sitting on the bench in the corner. Her pale blue trousers seemed offensively bright.

I got a similar feeling a few minutes later when, having left the dark cell, I walked into the large room containing six Rothkos. A huge canvas titled Yellow/pink 1955 was like the first sunny day after a long winter. It hurt the eyes but felt optimistic. Round the corner was a simpler picture, a field of dark blue and a field of very dark blue. I liked it, but it felt as if something was missing. My mind's eye supplied the missing item and painted it into the foreground: Ludvig Meyer, Advocate.

It was a long drive back to that bus stop in Cesis, but I was glad to have met him - and Munch. It's worth the trip.

More information about the exhibitions at the Mark Rothko Art Center is available at the official website.