Trends in raising and educating children are changing rapidly these days, and there is so much more choice: when I had my eldest son, the Japanese Yamaha music schools for toddlers were popular. Now that I’m raising my youngest son, preschools are more likely to offer a self-development system based on the methods of the Italian educator Maria Montessori (1870–1952) or invite parents to raise their children according to the care guidelines by Hungary’s Emmi Pikler (1902–1984), which urge parents to avoid over-stimulating the child. Young parents have countless informative articles, books and supporting materials at their disposal, covering various ways of parenting.

You can try this and that to find the most suitable model for your own family. Everyone’s heard of “French parenting”, which teaches patience and respectful relationships between the parents and their children, where children always finish everything on their plate, sleep throughout the whole night and don’t disturb their parents on their “child-free” time and territory. At one time, the ideal of the “Swedish mother” seemed most attractive to me: one should hide nothing from their children, nor should there be a compromise regarding the weather, meaning you don the thermal galonbyxor pants and spend hours at the park, below zero temperatures notwithstanding. The Swedish mother works, exercises and takes her children to after-school activities on her bicycle. She wears practical black clothing and always bakes the birthday cake on her own.

Truth be told, I was not able to stick to this mode of conduct for long. I was much too lenient and lazy. The Riga municipal dagis, or preschool, was unavailable for a very long time, and my children spend a lot of time indoors. With my second child, I am more similar to the traditional Japanese or nomad mother who stays with her child almost until they’re almost school age.

This isn’t possible for American parents, who don’t have paid childcare leave, and no chance to resume their career or to have the time to breastfeed their children indefinitely; nevertheless, they are quite interested in the effective parenting methods of other nations. A little while ago I read about an American family who are using Russian-style parenting, meaning children have to do their homework each day, eat their soup, study music, dance ballet, but they get to stay up as late as they want to. Internationally, the German parenting attitude is also esteemed highly. It allows children to play with fire (literally) and hurt themselves.

I know quite a lot about the more popular parenting tendencies, but in this muddle of cultures I have never thought – evidently, I lacked the confidence – to define what constitutes a Latvian upbringing. I realise I am talking about a very superficial and possibly foolish habit to divide upbringing by lines of cultural stereotypes and geographical location, but, despite being a native, I really do have trouble characterising Latvian parenting in the way it is expressed in French gallantry or Russian soup training. Folk songs and the ancient Latvian views on life have always seemed distant romantic echoes. Nevertheless, I have always known what to avoid: you must avoid the Soviet ways when newborns were not given to their mothers, when you had to feed them according to a schedule, then put them in a cradle and, in general, hand your children over to the system, which, as is well-established, did not really work and, in the end, did not make people anew as it promised it would.

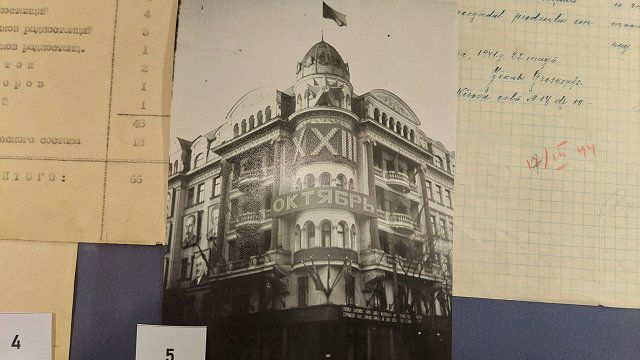

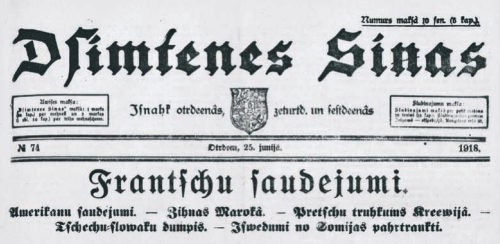

By way of personal observation, I know that, for the most part, modern Latvian mothers put the children’s priorities above their own. They try to ensure all-round development with after-school activities. They keep close tabs on their development, and gladly listen to modern psychologists’ advice advocating the principle of “naturality” and go back to work only grudgingly, following a lengthy childcare leave. To my oft-perplexed foreign friends, I explain the reasons for this trend by telling them of our social benefits, wages, and real estate values dictating priorities different from those of other Western countries. I explain it by telling them of the peculiarity of our young nation state, our lack of tradition… However, upon reading parenting and childcare advice in a hundred-years-old edition of the Homeland Newspaper, I was prompted to consider that this is not related to a lack of tradition, but rather the existence of one, and to the Latvian mentality, as well. At any rate, I was also very surprised too by the degree to which this advice for young parents - published the year the Latvian state was established - seemed… normal.

In 1918, during the war, when many Latvians had already been dispersed as refugees, among different bleak, trivial and grey columns there’s a naive and heartfelt section, “On Parenting. Written by the Old Uncle”, which describes in great detail the different stages of child development and the “sensitive workings of the soul”, i.e. psychology. At a time when the lack of schools, the hardships of life and the circumstances faced by refugees in foreign lands had made parenting all but impossible, this newspaper “uncle” (in reality, the advice was proffered by an unnamed pre-war educator) urges the public to think not about building new houses, but rather to promote the physical and mental well-being of the younger generation.

The uncle thinks that the soul of every child has “the makings of the human ideal” inside them and that the art of parenting can use this to form the basis of the child’s future.

He explicitly refers to parenting as an “art”, not a craft, stressing that “no mortal never has, nor will make it fully their own”. His first simile that caught my attention was an allegory about a tree and the work of the gardener: the child needs a lot of air and light, some rain and rarely some lighting. Just as you’d prune the dried-up branches of a tree, you should prune the children’s vices as early as one can, curtly and firmly, without long-winding sermons that make a child bitter and spiteful.

As is the case in horticulture, in children’s upbringing you must be able to marry the requirements of nature with those of culture. “Nature is immutable.” It can only be perfected and improved. The uncle believes that, in order to tap into the all-round potential of the child, he or she should study both indoors and outdoors, and in the city as well as in the countryside.

He invites readers not to limit the natural mobility of the baby and stresses freedom as an important prerequisite to a balanced development of physical and mental powers. The child should be allowed to run around and explore his surroundings, as well as fall down and hurt himself, in which case he should be pitied but he should also assume his own responsibility (he calls blaming an object a “reprehensible folly”). “The limbs of a child want to move ceaselessly...When one moves, muscles develop, and the sandwich mother made tastes good and there’s good sleep. The inability to sit still is in the nature of all young people. Merriment and liveliness are nested deep inside them.” This statement greatly shook my speculative conceptions about the strict discipline of the time long past. The uncle also urges for a quick reconciliation after scolding the child, because “the child’s happiness lies in whether parents can live with them” and that strictness should go hand in hand with affirmations of love.

Just like all of today’s leading psychologists, the uncle warns that children learn most of all from our example. We can teach them patience and other good qualities only if we have developed them within ourselves. He also urges the parents – mostly the mother, but the father too – to be responsive and answer the children’s questions, but to eschew their childish language and avoid singing praises for every tiny achievement. If the parents reply with interest and give explanatory responses for the child’s first six years, it is a guaranteed basis for further self-propelled learning at school, and that this will amount to a “hundredfold” repayment for the parent’s efforts.

What is the goal of this advice? “To bring up a human being with strong and healthy organs of the flesh, gifted with pure morals and decorated with the richest mental abilities best suited to the needs of our culture...The times alter, and things change, but the lofty goal stays the same.”

I’m currently re-reading John Medina’s Brain Rules for Baby: How to Raise a Smart and Happy Child from Zero to Five (2010). Medina is a modern American brain researcher and molecular biologist. The title of this book contains the age-old central question that at some point preoccupied the old uncle too: how can one raise a smart and happy child?

In conjunction to explaining nerve activity and the regulating functions of human genes, Medina uses the book to try to provide simple answers to the questions posed by American parents: Can I develop a baby’s mind from its very first days? How can I ensure that my child is accepted to Harvard when they grow up? Can upbringing ensure that my child will grow up to be happy?.. and so on. The author explains the prerequisites of human evolution, which have made human brains so big they can rule the world, but which have made newborns so unprepared for life that parents have to teach them most everything, including food ingestion and egestion, not to mention movement and socializing.

He uses the same simile of the tree and the gardener, or that of the seedling and the soil, to explain that 50% of the potential of a child’s happiness and intelligence depends on the genes and 50% on the upbringing. Medina always stresses that we are social animals and that our babies are born with an intention to communicate and create relationships with other people from whom they might receive help and learn life skills. We are a rare sort of animal that can survive only by cooperation, both in procuring food and looking after children.

Because a baby’s brain is so big, giving birth is a difficult and potentially life-threatening ordeal for human females, and a period of recuperation must follow. Therefore, others in the group are involved in parenting from the child’s very first days.

If you, as a parent, think you cannot make it on your own, that’s because it is not natural to do this alone, says Medina.

In order to reach through to the average reader, not only does Medina describe the growth process of the nerves and the brain, which develop with the speed of 8,000 cells per minute in the mother’s womb; he also differentiates the basic principles – or “brain rules” - that should be followed to ensure the best environment for the development of the budding new human being.

These are: the happiness of the mother and the quality of her physical and mental well-being; forging empathetic relationships; a sense of security for the child, which is the basis for truly free action; establishing friendly ties with the child; naming one’s emotions; a strong discipline that comes from a friendly heart; and the time we spend watching faces, not screens. To sum up, his writings provide a scientific basis for the basic parenting values that are listed in 1918’s Homeland News, but the researcher refers to the brain as the most complex thinking machine in the world, while the old uncle explains the workings of the brain by way of analogy to a telephone exchange, where environmental sensory input flows as it might through a telephone wire.

Furthermore the uncle, in addition to the “natural” operations, sets forth the “spiritual” operations that bring about “intuition”. “Intuition is the confidence that in my spirit, inside me there’s an ability to think, ponder, consider, notice, etc. For this we use simply the word ‘soul’.” The uncle considers educators who work with the child to be the teachers of the soul. “Each outside event brings about an inner intuition. Through outside events, the child, like the adult, creates inside his soul the images of the word at large...The child sees a person, her face, her pretty eyes; he hears the kind word, sees the soft hand that gives him food; he sees the cover of clothing, and an aggregate comprised of acts of noticing springs up in their soul: the image of mummy.” The soul is the “space” of such images or paintings, and the task of the educator is to help the child look after its contents and gain insight into each of its objects.

Despite the sometimes comical ring of the aged language, and despite the different misinterpreted and unexplored mechanisms of mental activity, the old uncle’s wonderfully poetic invitation promotes the development of a comprehensively educated, independent, harmonious and compassionate person. Meanwhile, the definition of soul as “an intuition that I have an ability to think” is one of the best-placed characterisations of consciousness I’ve heard.

For me, the Homeland News column brought about a surprisingly realistic realisation about the high ethical ideals and humanistic values that were important for the early 20th-century Latvian society in their everyday life, not only culture.

And why is it that I had thought differently, or, rather, that I had, without thinking about it too much, supposed that parenting standards were much lower in the days when the writers Jānis Rainis, Anna Brigadere and Kārlis Skalbe were alive? After all, my grand-grandmother, who was in all likelihood the target audience of this newspaper, did read Skalbe’s “Cat’s Windmill” to her children, with all the tale’s “sensitive” meanderings of the inner world.

Of course, I do not know who the “old uncle” is, but I assume his teachings must have been informed by the popular psychology of the day. At any rate, they have a lot in common with the conclusions on parenting by Maria Montessori and Emmi Pikler, both of whom lived at about that same time.

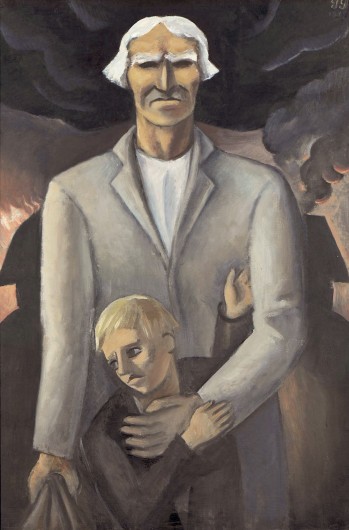

The uncle’s theories, however, have a local feature that brings his suggestions closer to animism, particularly stressing the role of the mother as an educator and protector.

He starts almost every single piece - and often supplements its middle parts - with an illustrative folk song (“As a little boy/I started off in the dark night”, “The sun is warm, my mommy nice/Both partake of the same good”, “Gently grows the little birch/Gently sprouts its tender leaves”, etc.), which supplements the idealistic message with, as it were, a pragmatic form that is found in nature, life, and history. For him, folk songs serve as references to what the readers know well and regard as self-evident, and the remaining theoretical developments don’t play an informative role but rather analyse that which is already known and remind readers about it.

From what I’ve seen of modern childcare and parenting books, or self-help books for parents, these, for the most part, do not introduce radical innovations, but rather urge people to see answers in what they recognise and what they want to see be brought to fruition. This does not, however, exclude the co-existence of disparate and contradictory methods as well as references to dubious sources (especially in matters related to feeding and “sleep training” the child). We choose to listen to what corroborates our existing beliefs. After all, someone as early as Aristotle believed that the reading process has healing properties on its own, despite the content and the answers provided.

Soviet literature does not teach or change society. The instilment of values, and the way they change or not, is rooted much more deeply in the culture of a given society. However, as concerns the genre of self-help for parents, I consider the advice of Homeland News’ old uncle to be, in many ways, a good example: mostly because he talks of ideals and of perfecting the art of parenting, without making parents bear the brunt of guilt for their shortcomings. And after reading this advice, I have formulated an answer with which I may one day shine on international mothers’ forums when there’s discussion about the principles of the clever French or the compassionate Thai way of parenting. I will proffer this nugget of folk wisdom substantiated within Latvian advice literature, for which I am very grateful to my mother:

“My dear mother,

Brought me up so kindly:

She waded through the mud,

Carrying me in her arms.”