There’s a tired myth about the most colourful neighbourhood in Rīga’s Latgale Suburb – the Maskavas Forštate, colloquially referred to as Maskačka: that it’s the city’s twilight zone, in which everyone is doomed to tantalizing punishment. Nevertheless, using the word “myth” to characterise this part of Rīga is not fully justified, as circumstances do not have to be out of the ordinary in order for people to experience something unusual in Maskačka. Each day, the eyes of sensitive citizens might seize upon embarrassing situations.

It is not a secret that the usual epithets that the public apply to Maskačka are emotionally loaded: it’s horrific; the most dangerous neighbourhood; it’s scary and disagreeable. There’s too much disorder, and Bohemian lifestyles are practiced out in the open. There are fewer well-off people here, and the shabby facades of the houses on the arterial Maskavas street serve as obvious proof that Rīga is still not finished, and that the area’s historical idiosyncrasy is still waiting for its rebirth or for 21st-century revitalisation.

The area’s urban environment is composed of architecture from several different ages – imperial, interwar, Soviet, and post-socialist. But the traditional 19th-century wooden buildings are in the most critical state. This is supported by the Latvian Television show, Adreses. In the show, architecture enthusiast Mārtiņš Ķibilds, together with Māra Upmane-Holšteine, a singer who wrote a song praising Maskačka, strolled around the neighbourhood streets.

They saw a contrast between the two former outskirt parts of the town – Maskavas Forštate and Ķīpsala – where workers and fishermen lived at some point in time. In these places, 19th- and 20th-century wooden architecture still stands relatively intact. Viewers are invited to think about their own relationship with the environment, architecture, design, and the stories about specific buildings and places that hold meaning to them. Meanwhile, the host asks the viewers, “The former charm of the wooden buildings in the outskirts of Rīga is disappearing everywhere, in Ķīpsala and Maskavas Forštate alike. The question is: what will replace it?”

Addresses mean people

What is an address? It’s a place where people live in, brought to life by the people themselves. Several excellent initiatives in Maskačka testify to this. For example, the energetic Baiba Giptere, an activist from the Association for the Development of the Latgale Suburb, landscapes the yards and takes care about cleaning them together with her neighbours. She serves as a rousing example to the others: “People like living here. Where the environment becomes more beautiful, tidier and more orderly surroundings soon follow. After we clean up a single yard, there’s another, and yet another still. This is the way the notoriousness of Maskavas Forštate will slowly fade into the past.”[1]

During the year when Rīga was a European Capital of Culture, the projects of her active neighbours – in this particular place, the Yard Movement of the Big Cleanup – brought attention to the neighbourhood for its favourable yard environment and the colourful and friendly neighbourhood festivals.[2] The flourishing corners and the blooming flower beds in the backyards, overtaken by nimble working hands, invite comparing the green spaces cultivated by activists to a local Rundāle.

In addition to this neighbourhood movement, there are other people brimming with initiative and creativity who undertake work for the public good in the part of Maskačka closer to the centre (Lastādija). The intellectual movement, the Free Riga association, revives empty buildings with owners’ permission, turning them into socially meaningful, public creative spaces. They encourage active local participation by regularly offering chances to apply for residency.

The activists of the T17 association, or the residence on 17 Turgeņeva Street, aim “to research, together with the other active residents, the life and stories of Lastādija – the old port neighbourhood – and to promote its cultural life and a sense of belonging”. The local map created in August 2017, Meeting Lastādija, is also quite attractive. In its latest version there are 38 points of interest that are topographically, culturally, historically and subjectively meaningful to the residents of Lastādija and Maskavas Forštate. But most importantly they reveal the human face behind places in the neighbourhood. The descriptions of the map are poetically witty and at the same time practically oriented urban miniatures.

An important aspect of the T17 initiative is its promotion of responsibility, individual involvement, optimism and non-forced enthusiasm for locally patriotic activity. It is somewhat unbelievable and difficult to comprehend, considering the misty outlook of the average Latvian, isn’t it? Nevertheless, it is quite real and quite wholesome. The objects and places found in the map show things many interested and active people have carried out. This is evident from the Krasta workshops where the Krasta Gallery is located; the musician Igo’s design workshop; the Bānūzis cafe which until recently hosted a charming antique shop; the Goodwill Studio that has a free, multicultural atmosphere and hosts board game nights and conversation courses of Lavian and English; the romantic Deficīts shop that sells cat souvenirs; the Humusa komanda, an example of social entrepreneurship with tasty Near East food; the Dagdas Street, which is undergoing a revival; and many other things.

The everyday life of the people of Maskavas Forštate testifies, indirectly, to the fact that local attitudes towards the neighbourhood do not assume a stance of forced positivity and that these attitudes are not a burden to be borne. Everyone who feels that they belong to Maskačka can belong to Maskačka. And everyone who wants to do something – everyone with an idea or a positive message, will find potential and hope here.

Difference and isolation

The urban difference (or isolation) of Maskačka is a historical phenomenon that starts with the construction of the old outskirts or Ārrīga (Outer Rīga) outside the old city walls, which stood until 1857 when they were gradually dismantled, causing the city to assume its modern shape. Testimonies to the fact that, outside the Riga City Walls, “the outskirts – Lastādija – were not as moral and obedient” and that it had “more wildness and audacity” were given by the author Rutku tēvs (Arveds Mihelsons) in his story, “The Kaiser of Riga”. Nevertheless such testimonies are to be found in other historical, literary, and newspaper and magazine sources.

The press chronicles have a lot to say about cases of disorder in the outskirts of the town – about traffic interference; smoking while driving; poisoning; a high mortality rate among new-borns and children; about theft and other unpleasant events. The 1889 Rīga City Police Newspaper says that “On October 7, articles of clothing worth 145 Rubles were stolen through the window of the 132 Lielā Maskavas street apartment, which belonged to the Jews Movši Šlahtmans and Miheļs Ovsejs”[3]. Another newspaper says that the “petite bourgeoise Domna Markova, entering the bar on 16 Jaroslavas street, fell off the stairs and broke her leg…”[4] Or, for example, “On the eve of August 28, near the house on 75 Maskavas street, a disagreeable person attacked the peasant Aleksandrs Mihelsons, who was walking down the street intoxicated, and wounded him in the back with a knife…”[5] Meanwhile “On December 17 at 193 Lielā Maskavas Street, during an argument the shoemaker Roberts Guts wounded the worker Karls Štolcs in the chest with a knife…”[6] Nevertheless, one cannot say there were significantly fewer events of this nature inside the city proper.

When becoming acquainted with Maskavas Forštate, one should take into account the fact that its impressive cultural history, which from as early as the 17th century is tied mostly to the ethnic minorities – Russians and Jews – is a wide, sensitive, and factologically, chronologically, scientifically and most of all emotionally capacious topic. It touches matters that a large part of society still distances itself from.

Valentīna Freimane, the excellent theatre and cinema historian, invites people not to confuse Putin for Pushkin when talking about politically charged matters touching upon the Russian community, which is one of Latvia’s ethnic minorities.[7] While historian Andris Caune, in the foreword to the book, The Latgale Suburb of Rīga, expresses a hope that the next generations of Rigans will respectfully remember “the previous generations of Rigans, of different ethnic groups, who have built and shaped this city”.[8] Here we should note in particular the Russian intelligentsia of Maskavas Forštate, the rich homeowners, the teachers, doctors, and traders. Similarly, the suburb is inextricably tied to the fate of the Jewish community in Latvia, testified by the ruins of the Great Choral Synagogue on Gogoļa Street, as well as the monument to Žanis Lipke and other saviours of the Jews. The Riga Ghetto and Latvian Holocaust Museum in Spīķeri, the Ebreju [Hebrew] Street and the former Jewish cemetery next to it must also be mentioned.

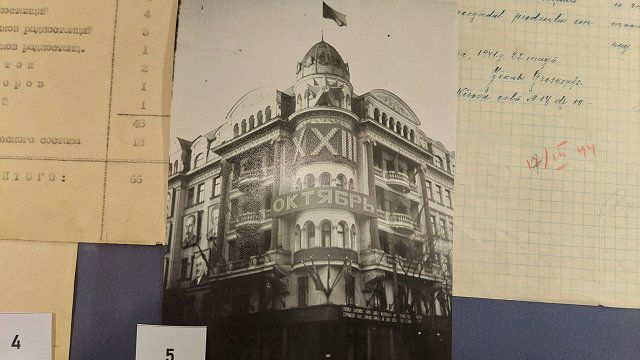

The 30 November and 8 December, 1941 mass murders in Rumbula, where the people confined in the Rīga Ghetto – established in the same year – were killed, are also part of the neighbourhood’s history. That is because the borders of the Riga Ghetto, which encompassed an area including Maskavas, Jersikas, Ebreju, Līksnas, Lielā Kalna, Katoļu, Jēkabpils and Lāčplēša Street, are a significant part of our Maskačka.

If You Like Maskačka, Maskačka Likes You

The legendary statement by film critic Viktors Freibergs, “Driving the No. 15 trolley is an existential ordeal”[9] expresses an essential message, characterising the local environment in a very straightforward manner. To the rest of the public, the reality of the trolley route running from the University of Latvia to Ķengarags is illustrated by the Facebook and Twitter account, The News of Trolley No. 15, (@trolejbuss15) which claims that you can only know Rīga and Latvia only when you know the No. 15 Trolley.[10] The administrators of the account ironically name the “pleasant aroma” of the trolley as one of its signature marks. Quite a few people routinely use social networks to share their experience in riding the trolley.

It’s not just the common people who are quick to demonise the neighbourhood. This is often aided by people known to the public. It begs a question of what’s one of the biggest problems of Maskačka? Often it’s the outsiders, or ārišķīgie[11]. This appealing designation is found in Luīze Pastore’s children’s book, The Story of Maskačka (2013). Its heroes, the dogs of Maskačka, have this to say about themselves: “We’re not bad. We are simply protecting our homes.” The work holds the humane idea – which largely applies to all of us, no matter where we live – that the neighbourhood is a sort of a centre of the world for its inhabitants. It is no accident that the dogs refer to the territory outside the gates of Maskačka as Āreja[12], which for the author serves as a witty reversal between the centre and the periphery.

Latvia’s centenary reminds us how useful it is to be aware of the potential of our immediate surroundings, and, in the context of Maskavas Forštate, to be aware of the attractiveness of the diversity of culturo-historical heritage. It would be useful to remember that not just Latvians are welcome guests in this celebration.

The Facebook page, If You Like Maskačka, Maskačka Likes You, reflects the neighborhood’s current events. It features articles and videos about colourful news of the neighbourhood. The title is a paraphrase of the tourist page If you like Latvia, Latvia likes you, made by the Latvian Institute. By way of analogy, there’s a rather simple and mostly painless chance to get to know, at least a little, the off-putting and mythical side of Rīga, which in reality is not a faraway, secluded location but instead a somewhat different Rīga that, sans snobbish gloss and polish, offers many nice locations just a few minutes away from the capital’s centre.

Only here you can meet the man who sings – loudly, cordially and completely off-key – the poems by Andrei Voznesensky from Russian version of the ballade “Million Roses” - Миллион алых роз. Only here can you find the tram conductor who on select stops steps off to feed stray kittens from a mystical-seeming red dish he picked up earlier; the spice store seller who offers hearty thanks to each customer; the girl who uses the tram to transport a gigantic silver five-point star; or the legendary triumvirate of Russian salesmen with a professionally polished offer: “Fellow passengers! Batteries, velour handkerchiefs, and super glue. Buy it – you won’t regret it!” And there are ordinary-looking, sometimes a bit intoxicated but otherwise cordial people who share poetic aphorisms in everyday speech: “Someone made it, someone else was late…”, “Don’t regret anything in life!” and so on.

And here, addressing the sceptics, we will put to use a dialogic dedication from the aforementioned guide, Meeting Lastādija: “How do you feel good in Rīga? Fall in love!” Our address is Maskačka.

[1] Baiba Giptere: "There was nothing here except grass stretching to one’s waist, it was all awfully overgrown." Saknes debesīs (TV show). 21 May, 2017.

[2] The Neighbourhood Festival in Maskavas Forštate. And what’s happening in your backyard? Rīga 2014. 16 September, 2013. Online source.

[3] Author unknown. “The daily chronicles of the city. Theft.” Rīga City Police Newspaper, No. 225. 10 October, 1889.

[4] Author unknown. “The daily chronicles of the city. An accident.” Rīga City Police Newspaper, No. 244. 8 November, 1895.

[5] Author unknown. “The daily chronicles of the city. Wounded.” Rīga City Police Newspaper, No 191. 1 September, 1985.

[6] Author unknown. “The daily chronicles of the city. Wounded.” Rīga City Police Newspaper, No 277. 20 December, 1895.

[7] Latvju Teksti. Literary journal. Latvian Literature Centre. No. 7, 2012, p 8.

[8] Caune, A. The Latgale Suburb of Rīga a Hundred Years Ago. The streets, buildings and people in the postcards of the first half of the 20th century. Rīga: Latvijas vēstures institūta apgāds (2013), p 8.

[9] University of Latvia Faculty Of Social Sciences. The faculty speaks. Source: https://www.szf.lu.lv/lu-szf-runa/

[10] Trolley No. 15 news. Source: https://twitter.com/trolejbuss15

[11] Translator’s note: Here, ārišķīgs (ostentatious) is a pun on ārējs (outer, outside).

[12] Translator’s note: Āreja can be taken to mean “the outside place.”