The war has remained part of Latvia's national consciousness, foreshadowing as it did the collapse of the Soviet Union and the air of resistance that was to be felt throughout the 1980s. Expressions such as the Black Tulip (referring to black planes carrying the dead home) are still current in Latvian letters.

Some Afghan War veterans – young adults who became Latvia's 'lost generation' – took part in Juris Podnieks' 1986 famous documentary Is It Easy to Be Young?, available with English subs on YouTube. For the occasion, LTV also interviewed one of the film's heroes, Guntis.

Director of National Botanic Garden soothes trauma with herbal therapy

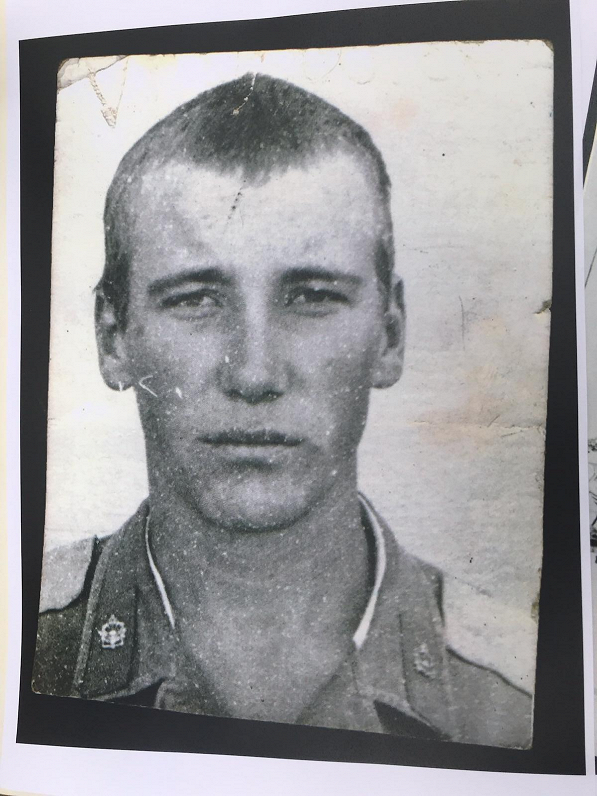

Andrejs Svilāns is the director at the National Botanic Garden. LTV met him at a rather silent time for the institution, with the orangeries at the garden fitted for winter and but a few student groups seen exploring the place.

Not many people know that Andrejs is a war veteran. At the beginning, neither did his parents.

"I lied. I wrote them that I was in Mongolia. It's just that I thought, well, if my corpse is to arrive in a zinc coffin – would it really matter if it comes from Mongolia or Afghanistan, if this way I can keep my family from unnecessary stress," he said.

Andrejs was sent to Afghanistan in 1987, at the age of 19. He had just finished his first year of studies at the Faculty of Biology.

"We arrived in Kabul. It was daytime, and it was scorching hot, the air was boiling over the desert plains. There was a mountain range in the distance, and the wind was scattering dust across the drylands. They took us to the front line in BMPs, and so it started," he said.

"I think that sending physically and psychologically unprepared people to Afghanistan is one of the gravest crimes of the Soviet regime. They weren't ready for these extreme situations, for the circumstances of war. When I got a very nasty infection on my leg, there were watery ulcers across, and I was sent to the sanitary department. There was a tiny soldier there [..] when you saw this brittle, broken, psychologically collapsed individual, you realized there's no place for him in the army, not to mention Afghanistan," Andrejs said.

A field engineer during the war, he recalls receiving orders to pick up potentially damaged mines around an ammo depot that had been destroyed. "There was an acquaintance who long stayed in my memory. We were on good terms, we went on smoking breaks together, talked about our lives and so on," he said.

"Then, as he was unloading [the collected ammo] from a truck for collecting it into a heap and eventually blowing it up, I am told one of the shells exploded in his hands. Half of his head was torn off, and so on," said Andrejs.

Upon his return, Andrejs went through a counter-cultural phase. "I wanted to everything opposed to logic when I returned," Andrejs said. He let his hair grow long, had several rings on his hands and routinely got drunk with the others at the biologists' dormitory. He said he'd done it to "wash his hands" after what he went through.

"The Afghans had nothing to thank for, as the entire mess was nothing but buttressing the Najibullah regime and carrying out Soviet-friendly policies. It was utterly pointless," he said.

His nature vocations, however, helped him leave the past be.

"When I was in Afghanistan, its nature helped me get through all the sheer stupidity. When we were at the warring region, winter receded and warm days began. The slopes at the foot of the mountains were a huge field of red-violet tulips, and there were rosier and paler and brighter ones too. And I thought, 'Geez, if only I could go there with a spade. There'd be so many new tulip species there,'" he said.

Alas, these were all growing between strips of barbed wire alongside with a notice that said, "Mines".

Keeping together with comrades-in-arms

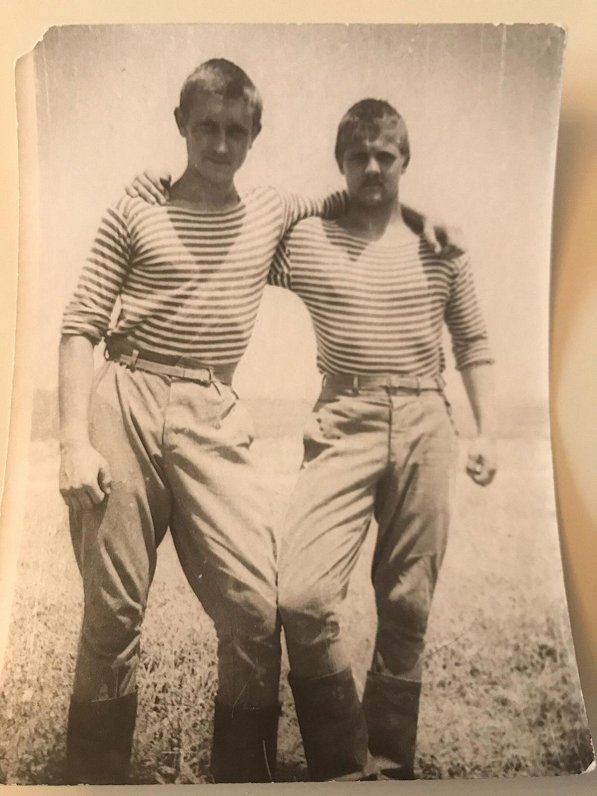

LTV met Gunārs Rusiņš at his home in Lielvārde, near the bank of Daugava River. He's now a retired major of the National Armed Forces. For the occasion, he also took along his mate, the veteran Guntis Vabole.

Gunārs was nineteen and Guntis was eighteen when the both of them were sent to Afghanistan. When Gunārs first saw combat, the war had just started. He was in Russia doing military service at the time.

"One night they woke us up and sent us to the warehouse for clothes. We were given warm jackets and started talking between us as to where we'd be sent. There was still something going on in Cuba at the time, but we thought, well, they wouldn't give us warm clothing if that was the destination," he said.

"You've the honor of going to Afghanistan to protect the conquests of the April revolution. Then we were given tents and shipped towards the train station inside confined vehicles," he said.

"We were dropped into Afghanistan. Our first trial by fire came quickly. We were just young lads who didn't think anyone could shoot at them. We were to pave the road for the other parts of the army that would enter with heavy machinery, as we entered without vehicles. Choppers dropped us off, we were given kirza boots so there's not as much recoil. But when pontoon bridges were drawn from interior Afghanistan, there were PAZ buses there, full of corpses," he said.

"When we entered the country, it was winter and locals said they haven't seen the likes of it for a long while. It was minus twenty at night and it rained throughout the day. We lived exposed to the elements. Back from battle, you fall limp and fall asleep at any place. And then you get up with your head frozen onto the terrain. It was a most common experience back then," he said.

He was wounded in July 1980 and allowed to return to Latvia for 45 days. But he was ordered to keep silent about what he had seen.

Gunārs and others could use the experience of Afghanistan to help the Latvian independence movement.

"I partook in the Baltic Way and elsewhere. Not only me, but many of these boys participated, as the experience of Afghanistan leaves its mark. These boys were able to help during the barricades. I was at the television building and had a brigade under my command. We were prepared for whatever was to come," he said.

Gunārs said, however, that the veterans should be provided with psychological help, "It was not a simple mission. It was war."

Many veterans can only scrape by with disability pensions of just €220 a month. "No one thinks of us and they don't tell about us in history lessons. The young generation does not know it. Who needs us? Nobody. We need one another to cheer ourselves up," he said.

He criticized Latvia's approach to the war veterans. "Only in Lithuania do they have social guarantees and so forth. Lithuania supports veterans of the Afghan war, as opposed to Latvia and Estonia," he said.

Gunārs was adamant that they had to go to war whether or not they wanted to, and that deserting might have put their immediate families at risk.

Guntis' life gets turned around in Afghanistan

One of the heroes of the aforementioned documentary where he is seen in high spirits, likely masking dread and apprehension, Guntis was heavily wounded in Afghanistan. During his compulsory military services, he was sent to a monthly training session in Uzbekistan and then on to Afghanistan.

"We had to protect convoys going to Russia. Empty upon return, these convoys imported planks, construction materials and food. If the freight was more dangerous, there were tanks in the avant-garde. They were always shooting at the first and last vehicles so that the convoy couldn't escape," he said.

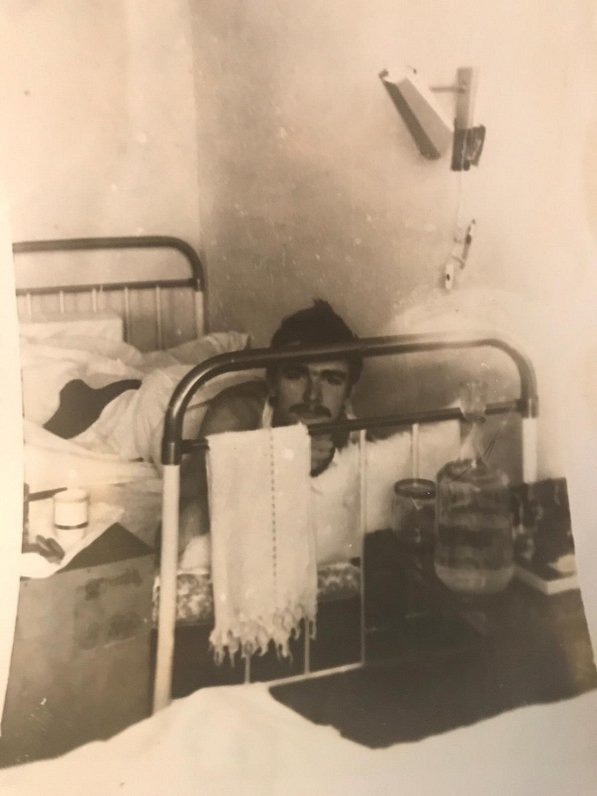

"We were wounded during cross-fire [..] I can't even recall how it happened. Molerov, a Lithuanian guy, told me afterward. When I was in Tashkent I came to after two weeks of unconsciousness. He came to me one-legged. Three of us were injured while inside an armored vehicle," he said.

"Molerov was sitting on a turret. He got three bullets in his knee. He slid back inside. I started bandaging him. The driver, Benashvili, started driving away and we hit a mine," Guntis remembered.

Guntis then underwent rehabilitation in Moscow, for about a year. "I was wounded in the legs as well. There was a concussion and a stress fracture in my spine. I was paralyzed but the operation was a success. For the outcome, a lot depended on my own actions, I had to practice and move around," he said.

Now an employee of a security agency, he earlier played sitting volleyball professionally. Competitions would take him as far as Japan.

"We do meet one another, but not as often now," said Guntis. Gunārs is one of his closest mates from the war.

As usual, veterans took to the memorial on Daugavpils Street, Rīga on the anniversary marking the end of the Soviet intervention. The Klusais dārzs park has a commemorative plaque honoring those who died in a war that was not their own.