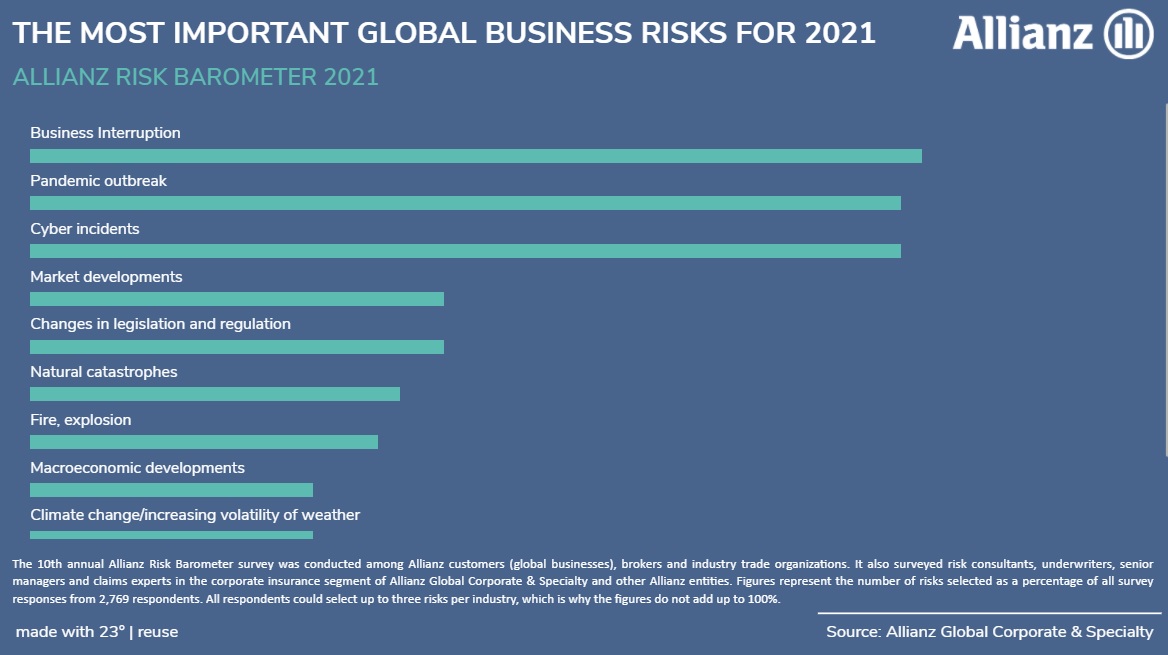

What are business leaders currently worried about the most? Given the unprecedented disruption caused by COVID-19, it is no big surprise that business interruption and pandemic outbreak take the top spots at the latest Allianz Risk Barometer 2021. The two main business risk are closely followed by cyber incidents that have been consistently high-ranked in the annual survey and remain a key peril for many companies around the world. Cyber attacks pose a threat to businesses of all sizes and seem to be threat that will not disappear anytime soon, not least because the pandemic has radically changed the working model in many sectors and businesses.

The COVID-19 outbreak has made remote working a sudden reality and matter of course for many employees. With more people from all sectors moving to work online, more organisations than ever are vulnerable to cyberattacks due an increased use of personal devices and apps for corporate purposes, which may fall short of required security standards. This has provided a fertile environment for cyberincidents and led to renewed concerns around cyber security and data breaches. Some security leaders are predicting even a COVID-like global “cyber pandemic” to be on the horizon.

In an era of stay-at-home orders, quarantines and lockdowns, online crime and attacks have become increasingly common. Cybercriminals are attempting to exploit the advanced networks and devices for their own ends by taking advantage of the ever-increasing use of online services by the public, governments and businesses.“Covid-19 has shown how quickly cybercriminals are able to adapt and the digitalization surge driven by the pandemic has created opportunities for intrusions with new cyber loss scenarios constantly emerging,” says Catharina Richter, Global Head of the Allianz Cyber Center of Competence.

Cyber attacks vary hugely by type, scale and severity and are continually evolving as criminals manage to exploit new technologies. Possible breaches span a vast spectrum range from minor attacks that are easily handled in house to major breaches that require a coordinated response involving leadership throughout the organization and the help of external actors. What they all have in common is that their nature makes it difficult to attribute responsibility for them to a particular actor or group.

Cost and damage

Global losses from cybercrime have increased by more then 50 percent since 2018 and are now estimated to total over 1 trillion US dollar – or just more than one percent of global GDP, according to a December 2020 report of the IT security company McAfee.

The most expensive forms of cybercrime are economic espionage, the theft of intellectual property, financial crime and, increasingly, ransomware. Another estimate by Cybersecurity Ventures expect cybercrime damages to even reach 6 trillion US dollar in 2021 – what would be the equivalent to the GDP of the world’s third-largest economy. Besides this direct financial damage there are wider knock-on effects and many hidden costs.

“Cybercrime is a colossal barrier to digital trust“, according to the World Economic Forum (WEF). “It drastically undermines the benefits of cyberspace and hinders international cyber stability efforts.“

The risk of cybercrime to business operations and profits continues to grow for many organizations around the world. Security researchers have seen a massive rise in ransom-related denial-of-service incidents over the past year that were not only larger in size and more frequent than ever, but also extended into more areas, targeting finance, government, energy and other sectors. The wave of extortion that began to spread in summer 2020 and in the course of which companies receive letters in which criminals threatened to launch a denial-of- service attack if the company did not pay the ransom also reached the Baltics.

In most cases, this was accompanied by a test attack and a threat of a more serious attack if the blackmailers are ignored and if the ransom is not paid on time, according to the state cyber security authorities in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.

The impacts of the attacks varied depending on the size of the attack and the existence and effectiveness of countermeasures. While in some cases they resulted in disruptions which affected the website of the company and lasted only a few minutes, the most influential attack seriously hampered the business operations of the targeted company. When the parent bank of one of the banks operating in Estonia located elsewhere was attacked, the bank's payment terminals could not be used for a few hours during peak time. This prevented or postponed transactions in the region worth millions of euros, according to a report of the Estonian Information System Authority (RIA) for the fourth quarter of 2020.

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, also the number of ransomware attacks targeting Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) services – a proprietary solution created by Microsoft that allows users to log into the corporate network from remote workstations – has steadily increased, according to analyses by IT security firm ESET and anti-virus specialists Kaspersky. In many cases, RDP is accessed through usernames and passwords, which can make them susceptible to brute-force attacks – a trial-and-error method used to guess login info and decode sensitive data. By waging such attacks against RDP connections, cybercriminals can access poorly secured network to run ransomware or exploit them to install cryptomining tools, keyloggers, backdoors and other malware on enterprise systems.

Being interested in the prevalence of RDP brute-force attacks across Europe, the digital marketing agency Reboot Online analysed the Kaspersky data and found out that the Baltics are high at risk. Lithuania, Estonia and Latvia are among the top 10 countries that are likely to experience RDP brute-force attacks.

More then 80 per cent of all network attacks in the three countries can be attributed to RDP brute-force attacks. Official data provided by state authorities seem to confirm this assessment: In Estonia, three-quarters of the ransomware incidents reported to RIA in 2020 were definitely or most likely committed using RDP. The situation in Latvia and Lithuania is expected to be similar. Small and medium sized enterprises in both countries have been frequently reported to be victims of these types of attack.

Targeting the information space

Beyond financial losses and the damage to the economy, cyber incidents can have deeper implications and far-reaching consequences. Government services and websites have become a tempting target in recent years for state-backed actors, cybercriminals and hacktivists, whose goals may not be financial but rather to cause maximum disruption and damage to a targeted state or major events around the globe. Politically motivated breaches can disclose sensitive data and information that undermine public safety and even amount to national security threats involving, compromised infrastructure, espionage or terrorism. Other emerging frontiers for cyber security are disinformation, fake news and big data that have increasingly being used to manipulate people’s mindset, heighten emotions and create distrust and chaos.

Major events like elections and Covid-19 present significant opportunities for state-orchestrated attack. During the first three quarter 2020 Google said it has had to block over 10,000 government-backed potential cyber-attacks per quarter – ranging from phishing attempts over spyware and malware campaigns to

denial of service attacks.

The COVID-19 pandemic saw cyber attacks directed at the World Health Organization and efforts to trick people into downloading malware by impersonating their staff. Other campaigns included targeting pharmaceutical companies and researchers involved in vaccine development. In parallel, social media platforms and governments have to battle the spread of coronavirus-related fake news and increased disinformation activites in the public domain.

Over the last decade, cyber security has indeed become a concerning problem for many countries. The primary target of states and nonstate actor have been the United States that have experienced the by far highest number of significant cyber-attacks between May 2006 and June 2020, according to an analysis of Specops Software. Significant attacks include assault on a country’s government agencies, defence and high-tech companies, or economic crimes with losses equating to more than a million dollars.

Baltic battling

While the Baltics are not listed among the top 20 countries in the ranking, it does not mean that they have been not target of mayor attacks. In 2007, during a bitter row with Russia over the relocation of a Soviet-era war memorial, Estonia was hit by a massive series of cyber attacks directed at government servers, banks and essential digital infrastructure – attacks the media dubbed the world's first cyber-war. A series of investigations into the attacks carried out from servers in Russia suggested there was an element of co-ordination behind them, though the Kremlin has always denied official involvement.

The attack on Estonia and its digital architecture propelled the issue of cyber defence to the forefront of the international community. Estonia's ability to stand up to the attacks led to the establishment of the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence in Tallinn in 2008. The multinational hub acts as a military think tank on cybersecurity and conducts research, training and exercises within four areas: technology, strategy, operations and law. Flagship projects include the Tallinn Manual, a guidebook for all things cyber security, and the annual technical live-fire cyber defence exercise Locked Shields.

At the same time, the Estonian government has amplified efforts to buttress its digital defences. Estonia became one of the first countries in the world to release a National Cyber Security Strategy, launched a new cyber command division within its military and is internationally advocating a strong regulatory framework. Estonia regularly raises the topics of cybersecurity – and has done also during its first year of its tenure as non-permanent member of the United Nations Security Council in 2020.

In a similar way also Lithuania has made cybersecurity a top priority and bolstered its cyber capabilities after repeatedly being victim to cyberattacks and online disinformation. Both countries rank high in the current ITU Global Cybersecurity Index as well as in the Global Index of Cybersecurity NCSI, while Latvia somehow seems to lag behind its Baltic neighbours when it comes to cybersecurity commitments and capacity building. Yet all three Baltic states have been amassing decades-long experience from combatting disinformation, fake news and hacking attacks.

Pandemic brings cyberattack surge

Countering moves online remains challenging. If the cyberattacks of 2007 were a wake-up call for the area of cybersecurity, then the COVID-19 pandemic is ringing another alarm bell for the need to reinforce and fortify cyber-defence.

The pandemic has accelerated technological adoption, yet exposed a number of shortcomings, vulnerabilities and weaknesses in IT systems and digital environments around the world including the Baltics. Public authorities in all three countries are currently probing serious cyberattacks against both government networks and critical information infrastructure. These malicious incidents include malware, system intrusion and compromised systems. Most notably Lithuania has reported a number of sophisticated cyberattacks, but also Estonia and Latvia have experienced severe and complex attacks on the networks of state agencies.

In Lithuania, the presence of NATO troops has long become a favourite informational attack vector. There have numerous examples of fake news about the allied forces allegedly representing a safety hazard or even security threat to the civilian populations. In many cases they involve complex cyber-information attacks.

Most recently, more than 20 public sector websites were hacked to post three types of fake news articles in December, according to the National Cyber Security Centre. One of them claimed a Polish diplomat was caught smuggling narcotics, firearms, explosives and extremist materials into Lithuania and had been detained on the Lithuanian border.

Other fabricated news that were previously circulated claimed that Vilnius wanted US nuclear weapons stationed on its soil, a German NATO tank desecrated the Jewish cemetery in Kaunas or Lithuania was calling for "a peace-keeping force" to be sent to Belarus. All these disinformation efforts were distributed by

fake press release.

This feature appears in the latest edition of the Baltic Business Quarterly magazine prduced by the German-Baltic Chamber of Commerce in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, and is reproduced here by kind permission. Find out more at the official website and read the rest of Baltic Business Quarterly magazine here: https://www.ahk-balt.org/lv/publikacijas/zurnals.