The century old metal wreaths and so-called wreath “baths” are now covered by a layer of dust. They were quite expensive and only wealthy people could afford them. Historians are shining a light on this forgotten tradition.

Largest collection in the Baltics

The Jaunrauna Chapel attic holds the largest collection of surviving metal wreaths in the Baltic countries.

“We haven't found this many metal wreaths from the previous century anwywhere else. There are about 50 here. They still haven't been properly examined and counted,” said Grīnbergs.

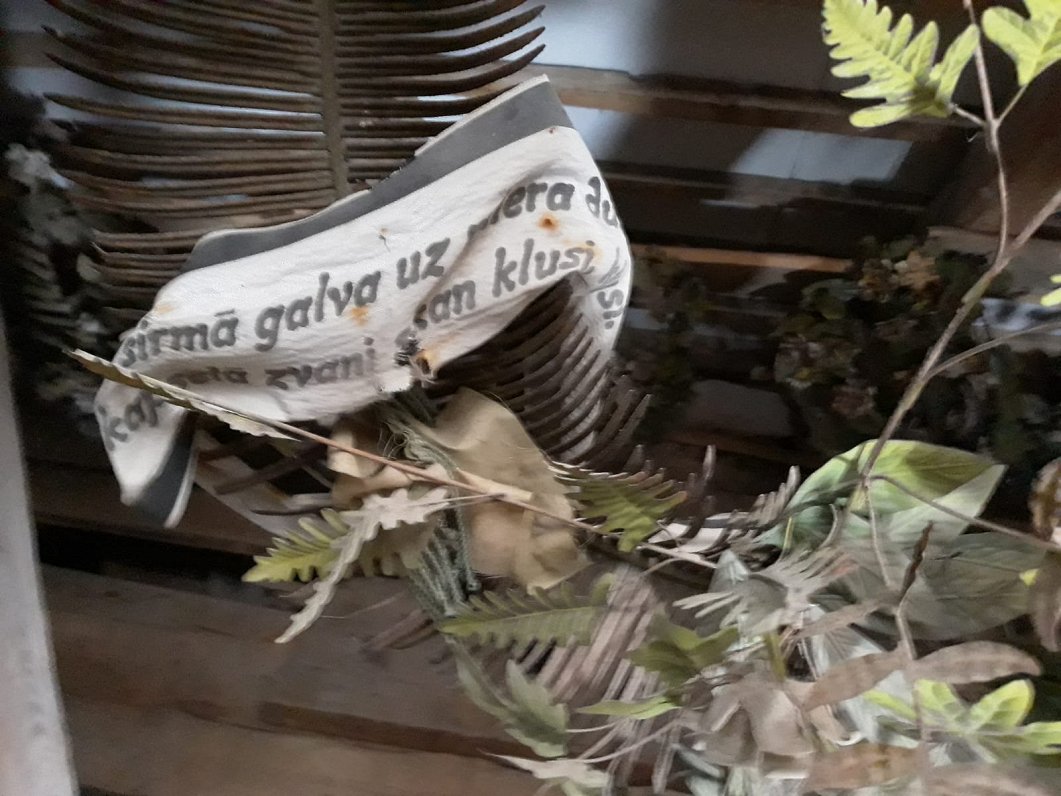

Some of the wreaths are even over a meter in height. The ones that still have intact ribbons are helpful for determining the age of the wreath. Grīnbergs pointed to one that reads October 1920. “It's great that the ribbon has at least partially survived. This way we can tell the age, we can already tell who it belonged to. In what language it's written, here everything is in Latvian, so it's a true Latvian tradition,” said Grīnbergs.

“From a cultural heritage perspective it's truly a unique collection. The material value is of course symbolic, although in actuality it's practically nothing. But the cultural heritage value is huge,” continues the historian.

Unique funeral tradition

This unique tradition is no longer practiced today. It's possible that the tradition was followed in winter when live flowers weren't available.

“We live in a part of Europe where cemetery culture is very developed. Cemeteries are green, but during winter periods there of course aren't flowers, so flowers and wreaths were expensive and less available,” says Grīnbergs.

Most likely that was one of the motivations why these types of wreaths appeared somewhere in the 19th century. People wanted something longer lasting and enduring,” he continues.

Metalworkers and workshops

Historically there were special workshops for making headstones and other cemetery inventory.

“But in reality it was metal artists who did this. They worked with various stencils. They also had catalogues. It's the careful work of a metal worker,” explained Grīnbergs.

The wreaths were made in Rīga, Liepāja, Sabile, Talsi and other cities. The workshops also repaired the wreaths. An advertisement in the Maliena News in 1932 says:

“.. the firearms workshop is accepting metal wreaths for repair and painting.”

(Maliena News, 24.11.1932, nr. 377)

The wreaths were also a Latvian export. The Latvian Soldier writes:

“.. in August Latvia exported to Denmark (..) 200 kilograms of metal wreaths...”

(Latvian Soldier, 06.10.1929, nr. 227)

Oak leaves, roses and lilacs

Traditionally the wreaths included oak leaves. Looking at the details, you can see that each vein is crafted to the last millimeter. “The wooden acorns are delicately attached and have been well preserved here. Roses are a very traditional flower, which is reproduced in various stages of bloom, as buds and roses,” says Grīnbergs. “Each [lilac] cluster is a true work of art. The roses – quality crafted petals. Also painted, all of the inside parts.”

The research expedition also included a biologist to help identify the plants. The wreaths had not only traditional flower, but also more rare ones. “We found not only rare plants, but also completely made-up ones. For example, roses with oak leaves. The types of forms that just don't exist in nature,” said Grīnbergs.

Expensive prices

The metal funeral wreaths were more expensive than regular evergreen wreaths, not just anyone could afford them.

“From a price point the metal wreaths were somewhere between a very intricate natural flower wreath and a memorial. In Jaunrauna we've found ribbons on individual wreaths where you can read that they were placed by a collective,” said Grīnbergs.

Thefts prove how expensive the wreaths were. The Free Word writes in 1928:

“Not long after the carter Gusts Dreimanis died his grave was regularly robbed. Two bands were taken from the graveyard and several valuable decorations were stolen from the metal crown. There are suspicions that the items stolen from the graveyard have directly or indirectly have made their way to a crown shop, because grave robbery is a common occurrence in Valmiera. The relatives swear to catch the thieves sooner or later.”

(“Free Word”, 10.02.1928, nr. 67)

Disappearing tradition

The historian became interested in the subject while on an expedition looking for ancient rocks, trees and cultural heritage sites. “In certain cemeteries in Kurzeme we found metal wreath baths, and the first place was in 2008 at the Dārta cemetery, where there are several of these wreath baths. Two years later in the nearby Klopene cemetery we found more. And more, and more, over the next years in more places. And then we got the impression that this is something that we really don't know anything about, that it's an old tradition, which has in fact passed,” said Grīnbergs.

“As a very valuable part of cultural heritage, it's disappearing, and each year there are even fewer left,” said the historian.

With the beginning of World War II it can be presumed that the craftsmen died. The workshops where these objects were created were demolished, as they were in big cities. In reality, after WWII the tradition is as if cut off with a knife and no longer practiced.

The State Culture Capital Foundation has supported expeditions to northern Vidzeme and Kurzeme, however Zemgale and Latgale have yet to be explored.

“The total of metal wreaths, including wreath baths, is currently over 300. Some are well preserved, and for others there are only details and a fixed location that there was something at that location. But today there's practically nothing to see,” said the historian.

Ironically it's in the more remote, desolate regions where the graves aren't as well-kept that many historical pearls can be found today. In cities where cemeteries are well cared for, there is practically nothing left of this tradition.

Before this year no museum has displayed these types of objects. “This year I found two wreath baths near Kuldīga. One was already thrown out. The Kuldīga Museum took it for preservation,” said Grīnbergs.