Baltic occupation by the Soviets: Incremental works best

After the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact was signed, Stalin and his henchmen were in no particular rush to destroy the independence of the Baltics. The Soviets achieved this goal slowly but steadily, with each ultimatum leaving room for hopes and illusions over preserving at least a smidgen of Baltic statehood. That is, until July 21, 1940 when the so-called "people's parliaments" asked to add the Baltics to the brotherhood of Soviet republics.

This approach gave the Soviet Union two important advantages:

- They had room to maneuver in face of international pressure, as the process could be paused or even backtracked a bit;

- A slower approach allowed reducing the chance that meaningful resistance would take place. With each of the ultimatums, the Baltic governments faced a choice of acceding or risking all-out war.

The Finnish government chose not to submit and thus went to war. Despite heroic resistance, Finland was defeated. In spring 1940, the losses seemed larger than any possible benefits. 70,000 Finns died in the war, the Soviets annexed 11% of Finnish land and gained the right to set up military bases on Finnish soil. There were many people in the Baltics and Finland who thought that the Winter War had been useless and the Baltics' submission a rational policy.

Sensible as it might have looked, this policy met its limits fairly quickly. Following Soviet ultimatums over bringing in the Red Army, on June 15 and 16 the Baltics lost what remained of their independence. The authoritarian presidents of Latvia and Estonia, as well as Lithuanian PM Antanas Merkys – Lithuanian president Antanas Smetona was the only to ask his army to resist Soviet attack, but as the government refused he chose exile – thus became unwilling, but obedient instruments to help instate Soviet power.

But in summer 1940 there was unanimity among the Baltic political elites over that a military conflict with the Soviets would have been an utterly hopeless undertaking.

Instead, they preferred to wait. Perhaps Soviet policies wouldn't be as radical as thought, or maybe the international situation would become more favorable. As late as July, Estonia's president Konstantin Päts told German diplomats he had reason to hope that Estonia would not become Sovietized.

Baltic leaders used their diplomatic representations in the US and the UK as collateral. Should the worst come to pass, members of the exile would have a chance to represent their countries internationally, and the Baltics would go on existing at least in legal terms.

(Read more about the life and times of Latvia's chief post-war diplomat Kārlis Zariņš.)

Schoolboys for Latvian freedom

Latvia's authoritarian president Kārlis Ulmanis was subdued by the Soviets, and his attitude reflected that of the other Latvians, at least initially. The occupation was not followed by protests or partisan warfare. The main potential source of resistance – the Latvian Army – was slowly integrated into the Red Army. The Soviets turned it into the Red Army's 24th Territorial Rifle Corps, while the soldiers' and officers' political opinions were closely monitored by the NKVD secret service. The Soviets took great care to isolate the army from the rest of the public, and pogroms on nationally-minded soldiers followed soon after, culminating in June 1941 in Litene, where 50 soldiers were killed and about 560 sent to gulags. The interior forces such as the police were also subdued quickly.

What posed the most serious problem for the Soviets was the Aizsargi (Defenders, Guards) paramilitary organization. There was no place for it under the new regime. While the organization was disbanded on June 23, 1940, its members, numbering at more than 60,000, still were a force to be reckoned with. There were 19 regiments of Aizsargi across the entire Latvian territory, and disbandment did not magically erase the organizational skills they had.

And Aizsargi were the first to embark on real resistance against the Soviets.

While Ulmanis' legacy is debatable, his patriotic education system had created the second main source of resistance – a fastidiously patriotic generation which had grown up in an independent state and did not want to lose the ideal of Latvia. As opposed to their leader Ulmanis, the younger generation was not averse to risk, and resistance-ready Aizsargi found companionship in enthusiastic teenagers.

Waiting in the wings, but never taking off

By late summer 1940, a number of anti-Soviet resistance groups had sprung up in Latvia, chiefly made up by teenagers as well as members of the Aizsargi. These were called A Free Latvia, the Latvian National Legion, the Battle Organization for Freeing Latvia, etc. They had ambitious plans.

They wanted to organize massive military resistance in Latvia, hoping to involve a foreign power in the fighting too.

Depending on the sympathies of any particular group, the hopes were staked on either Germany, or the UK. The leaders of some groups even tried sending letters to foreign governments. Particularly long-standing among these groups was the unusual expectation that Sweden would become involved in the war, mirroring the "good Swedish times" of the 17th to the early 18th century.

To reach their goals, the resistance groups set up rather complex organizations with different departments for propaganda, intelligence, finance, foreign policy, health, etc. These groups both collected donations and hoarded weapons. There were also attempts to set up inter-group coordination.

They did not reach the level of real armed resistance, however. Contrary to their hopes, no resistance group rose to the level of a mass movement, with the largest reaching some couple hundred members of which just dozens were active. Most military refused to join as well. Therefore the resistance was limited to disseminating propaganda leaflets and illegal press, as well as painting patriotic slogans on house walls.

The most pressing problem in the early stages of the resistance was the lack of experience among the underground resistance.

Members often based their views on conspiracies in what they had read in spy novels, and the Soviet secret service had created full dossiers on the most active members soon after the groups were set up.

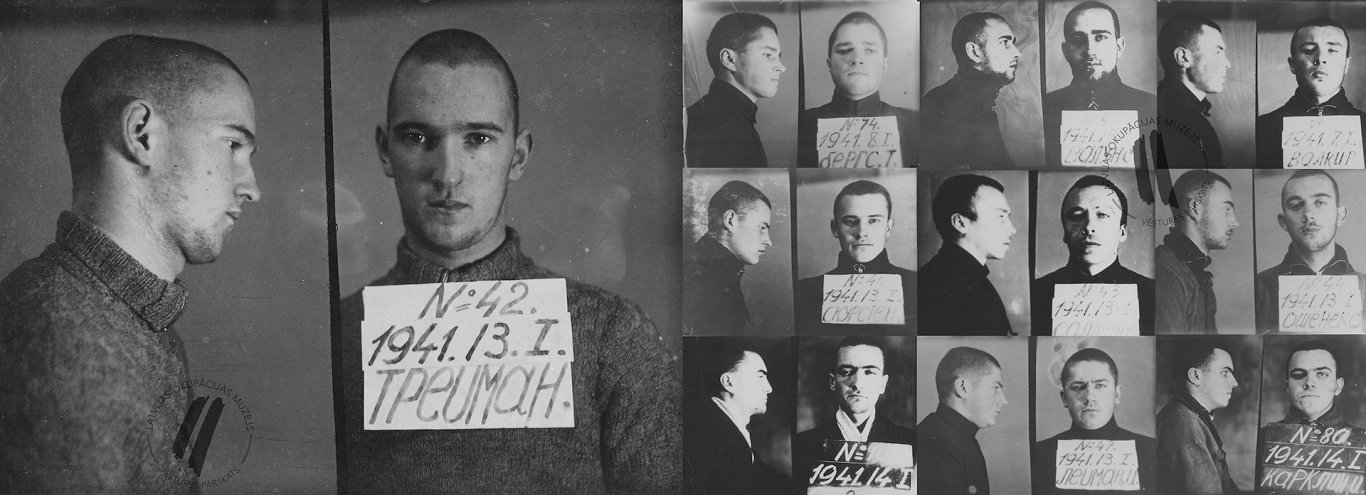

In late 1940 they started arresting members of the resistance. Tortured, many divulged information about members the Soviets didn't know about, and by spring 1941 most of the active resistance groups had been destroyed. Grownups were usually sentenced to death, while pupils were in for a long haul at the gulag.

Bitter pills to swallow

The NKVD's perceived threats to the Soviet regime weren't limited to the active resistance group, and Soviet repressions affected more and more people. But until June 1941 the repressions were usually limited to individual cases. June 14, 1941 was a turning point. The news of mass deportations shocked the Latvian public and, as news of the approaching German army arrived in late June, the former Aizsargi started setting up partisan groups and engaged in armed combat against the fleeing Red Army.

At last, the military resistance envisioned by the Aizsargi and patriotic teenagers had come to fruition, and as they had expected it happened with another great power becoming involved. But the reality they were now to face was far from what their ideals dictated.

In lieu of freedom, what they had was one criminal totalitarian regime being replaced by another criminal totalitarian regime.

But those ready to fight for Latvian independence now faced an awkward dilemma. Is it acceptable to join an invader regime to fight another one? No matter what the answer, the year under the Soviets had proved that the naive idealism of the resistance was not suitable to fight invading powers.