Extraordinary developments lead to extraordinary measures

In spring 1940, Kārlis Ulmanis observed European events with great concern. First, Nazi Germany occupied neutral Denmark and Norway. In May, fighting resumed at the hitherto quiet Western front. Germany advanced rapidly, surprising the Allies with manoeuvres through Belgium and the Netherlands. The neutrality of these two countries was ignored as well.

While Latvia was still formally independent and neutral, by now Soviet troops and military bases had been stationed here for more than six months. For all this time, Ulmanis had counted on that the UK and France will succeed in regulating the conflict with Germany. Should the allies win or reach an agreement, Latvia would have diplomatic leeway with the goal of curbing Soviet ambition. But if the Nazis emerged victorious in continental Europe, it would be unlikely that the Allies would have moved a finger to prevent Soviet aggression. Instead, Germany could have turned against the Soviets and in that case too Latvian independence would come to a halt.

Weighing these scenarios, Ulmanis decided that a foreign service diplomat should have the right to represent the country in case of an emergency.

From the candidacies of Kārlis Zariņš, envoy in Britain, and Alfrēds Bīlmanis, envoy in the US, preference was given to the former. A senior diplomat, Zariņš had a more prestigious office (the movers and shakers of Latvia's foreign policy saw the UK as the most important country in the world during the inter-war period). On the other end of the pond, Bīlmanis would prove to be a worthy deputy to Zariņš. On May 17, the Cabinet of Ministers formulated the decision and sent a secret message to the two diplomats. A month later, on June 17, Soviet tanks arrived in central Rīga.

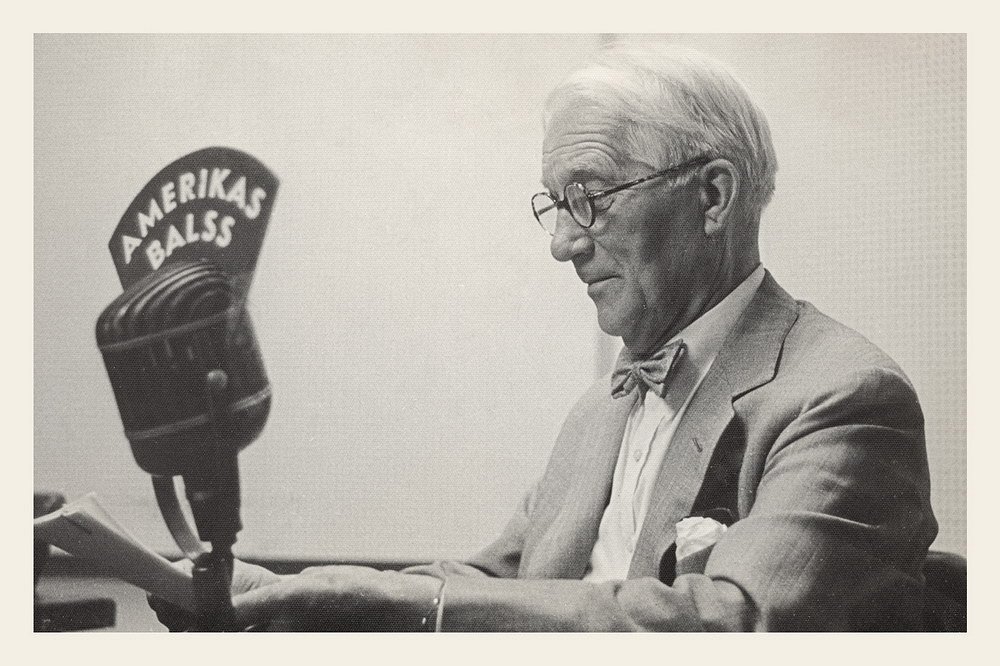

Experienced diplomat entrusted with supreme responsibility

Zariņš was one of the most experienced Latvian diplomats. As an official at the Foreign Affairs Department of the Latvian Provisional National Council, he helped advance Latvian interests even before the state was established. As early as the Independence War, he became an attaché at the Paris peace talks and then served as an envoy in Scandinavian countries and as Foreign Minister under PM Marģers Skujenieks (1931-1933). After stepping down, he became an envoy in the United Kingdom. Zariņš had no political affiliations and was found to be useful under Ulmanis as well, allowing him to preserve his office following the coup.

And on May 17, 1940 he received clear testimony that he was held in very high esteem.

The Cabinet of Ministers ordered that the extraordinary privileges would become official if promulgated by the Foreign Minister, or automatically if Zariņš is unable to contact the Minister. On June 17 Ulmanis addressed the people with the famous talk, "I shall remain in my place; you remain in yours."

This did not make it clear whether Latvia still was an independent country. Throughout July, the Soviet powers used Ulmanis' signatures to destroy what remained of the country's sovereignty until, on July 21, the so-called People's Saeima (Tautas Saeima) made a sham request to add Latvia to the Soviet Union. The country had practically ceased to exist, but for as long as Zariņš' diplomatic service existed there would remain a glimmer of hope.

Diplomatic battles

The US and the UK did not recognize Latvia becoming a part of the USSR and still considered Latvian envoys diplomats. But in summer 1940 both countries were not in a position to provide practical assistance to prevent the occupation. The UK was alone at war against Nazi Germany, while the majority of Americans opposed participating in European conflicts. Despite this, Latvian diplomats continued unceasingly to report Soviet repressions in Latvia to the British and American government as well as the international public.

The German attack on the USSR became an additional threat to the continued existence of the Latvian diplomatic service. First of all, the USSR and the UK – and, from late 1941, the US as well – were at the core of the anti-Nazi alliance. Secondly, some Latvians enthusiastically cooperated with the Nazis, threatening Latvia's image. It's no secret that Soviet diplomats asked the US and the UK to close off Latvian foreign services and return the corps to their "homeland". Soviet propaganda likewise tried linking Latvian independence fighters with the fascists.

Throughout the war, Zariņš and Bīlmanis had to hand in note after note to remind the world about the state of affairs in Latvia, dispelling every tiniest rumor.

When the Latvian Legion was formed, it was up to the diplomats to explain that conscripting Latvian citizens into German armed forces was illegal and that Latvians did not sympathize with the Nazi regime. They were also to repeat incessantly that the legion's official name, the Latvian SS Volunteer Legion, was misleading as the majority of Latvians faced forced conscription.

As the result of the laborious efforts of Latvian, Estonian and Lithuanian diplomats, the matter of Baltic occupation current topical throughout the war. But should the great powers come to an agreement, the Baltic diplomats wouldn't have a way of changing the situation. Therefore the meetings between US, British and Soviet leaders at Tehran, Yalta and Potsdam always caused great worry. There was never complete certainty that the final word over the future of the Baltics wouldn't be uttered amidst carelessly blown cigar smoke.

Despite the worries, neither Roosevelt, nor Churchill (Truman and Attlee in Potsdam) accepted a rash compromise. The Baltic matter remained ever unsolved and, with the advent of the Cold War, the US and the UK became far less willing to legally recognize the Soviet borders.

Helping refugees, fighting Soviet trickery

The end of the war brought new worries to Zariņš. Now there were 120,000 Latvian refugees westward of the Iron Curtain. It was, of course, important to aid his compatriots, and Zariņš' efforts did much to encourage the US and the UK to provide the best possible care for Latvian displaced persons (DPs, or dipīši).

Zariņš stood up for the interests of the former Latvian legionnaires, explaining that they are not Nazis and are in fact very loyal to the Allies. As relations soured between the Western Allies and the USSR, Zariņš took every opportunity to stress that the legionnaires fought communism and could prove to be of great value in future confrontations.

Throughout the first post-war years, Zariņš repeatedly visited Latvian refugee camps and took up monitoring the coordination among the DPs.

In addition, Zariņš and other Baltic diplomats had to look out for Soviet trickery. In summer 1946, before the Paris peace conference where Italy, Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, and Finland would sign peace treaties, the Soviets included the Foreign Ministers of Latvian, Lithuanian and Estonian SSR in their delegation. If they were to sign a document that had the signature of an Allied country, it would mean that these SSRs would have been recognized as legal.

That's why Baltic diplomats launched a massive campaign until British Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin – a Labour politician who nevertheless hated the communists and the USSR, therefore sympathizing with the Baltic cause – gave a promise that this wouldn't be allowed to happen. The International Refugee Organization, partially responsible for providing for the DPs, also caused worry. Several organization members thought that the Latvians suspected of collaboration with the Nazis should be sent back to the Soviet Union. To stop this, Zariņš and other Latvian diplomats took great care to cultivate a positive image of the Latvians.

Ulmanis' legitimacy questioned by the exiles

On the other hand, Latvian exiles were in a position to discuss questions that the Ulmanis regime had brushed aside. Social democrats such as Arvēds Bergs, as well as people tied to the Latvis nationalist newspaper and simple advocates of democracy questioned the legitimacy of the Ulmanis regime. Having been isolated from political life, the exiles were finally able to engage in free discussion and challenge those loyal to Ulmanis.

One of the most important questions was whether the Satversme (Constitution) was still in force. On May 15, 1934 Ulmanis had illegally put an end to the Latvian Constitution, and during his years in power no-one did anything about putting the state's constitutional basis into order. Therefore the Satversme had remained as it was on May 14, 1934. Legally speaking, therefore, it could be argued all of Ulmanis' decisions following the coup were illegal, including the May 17, 1940 decision over granting extraordinary privileges to Zariņš.

As late as August 13, 1944 the founders of the Latvian Central Council in Rīga agreed that the Satversme is still in force and that the 4th Saeima remains in power until the next parliamentary election. According to the Satversme, the Saeima Chairperson assumes the office of president if the president is dead or unable to carry out office duties. Pauls Kalniņš, the long-time Saeima Chairperson was still alive at the time and was likely to have insisted on his rights in exile to assume presidential powers and name the exiled government. But he did not survive through the first year of the exile and died on August 26, 1945 in Austria.

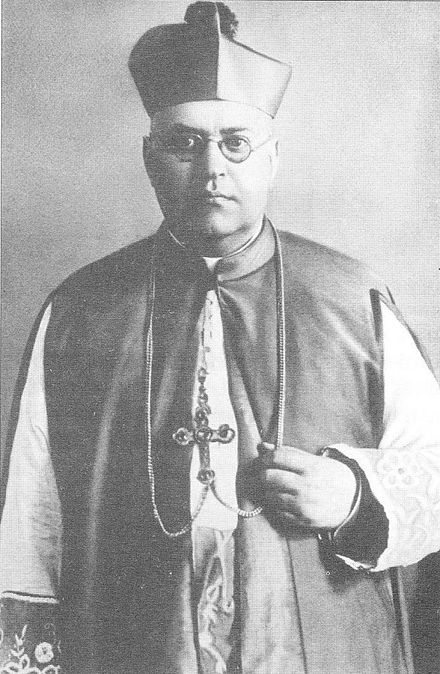

Jāzeps Rancāns, a bishop and official, succeeded him in the office as per the procedure set forth in the Satversme. In effect the president of Latvia in exile, he nevertheless abstained from naming a new government, as Zariņš strongly objected to this, and the US and the UK chose to support the continued supremacy of the foreign service due to its stability.

Following 1950 there was no more talk of setting up an exile government. Zariņš continued to lead the diplomatic service until his death in 1963 while Rancāns was, by some exiles, considered president until his death in 1969.