More about the cycle of events can be discovered at https://www.gramatai500.lv/ and for more about the Latvian National Library and its constantly changing exhibitions and collections, visit: https://www.lnb.lv/.

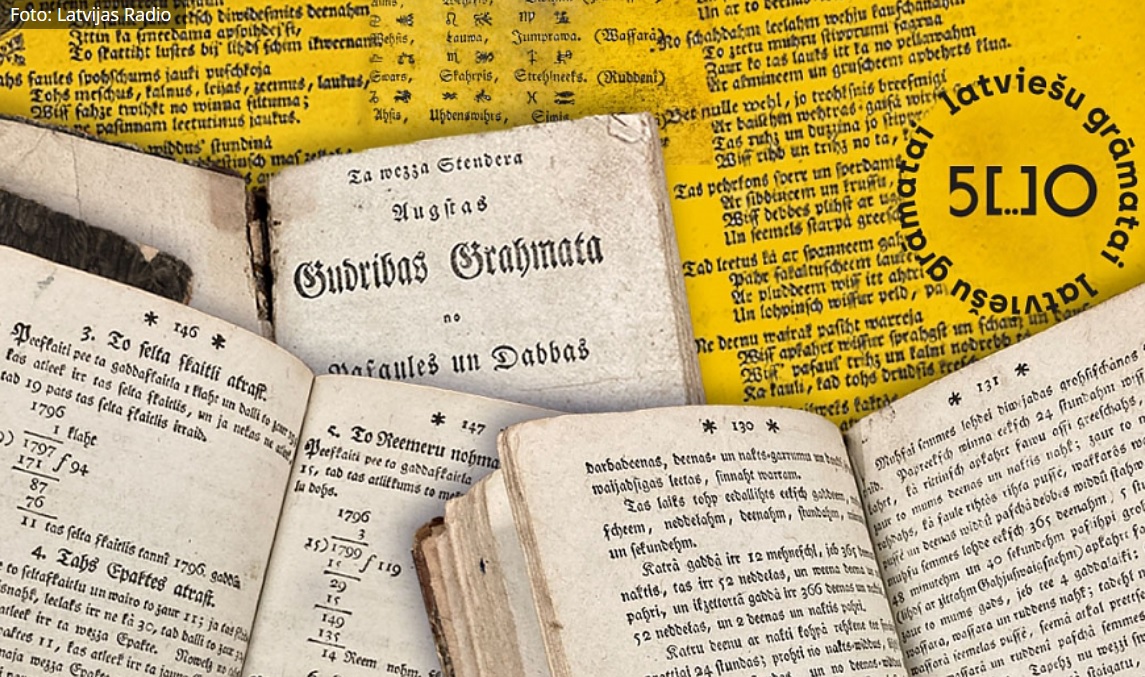

How Old Stender laid the foundation for description of the Latvian language for the next hundred years

Many events are symbolised in our minds in the form of specific personalities, for example, Ernst Glück for the Latvian translation of the Bible, Juris Alunāns and Atis Kronvalds for the National Awakening, Jānis Endzelīns for the modern Latvian language. Another symbol of this kind is Gotthard Friedrich Stender (1714–1796), also known as Old Stender. But he symbolises not just one event, but, in fact, an entire century, as he is both the most prolific and the most important Latvian author of the entire 18th century.

Moreover, his contribution to the development of the Latvian language and literature is extremely multifaceted. Old Stender is not only the author of the first collections of secular poetry and secular stories, the first book on a model of the universe, but he is also a scholar and developed a description of the Latvian language.

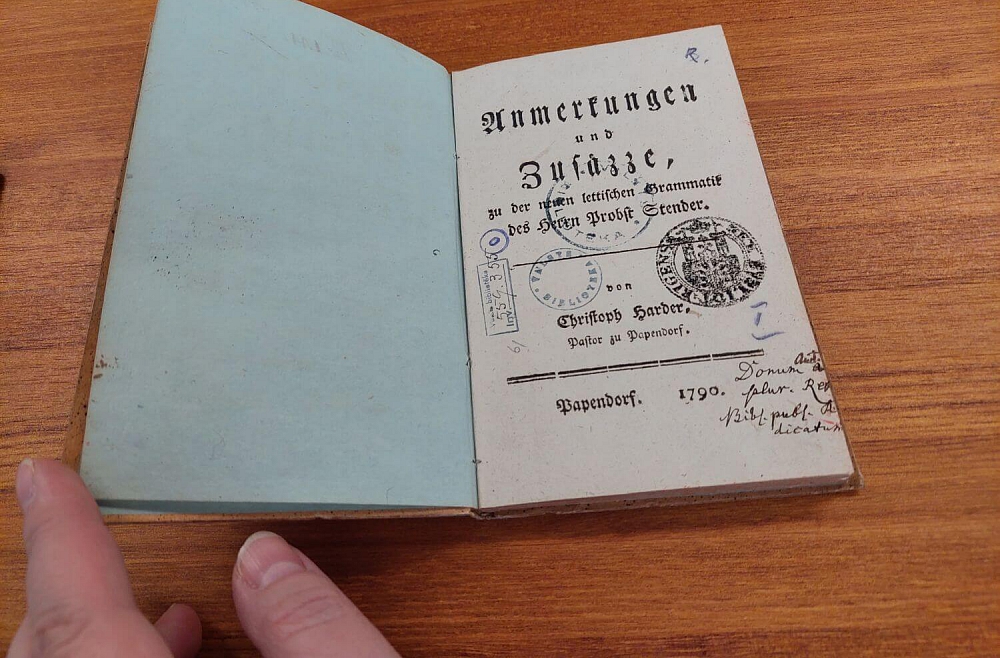

With his two grammars, Neue vollständigere lettische Grammatik [New, more complete Latvian grammar] (1761), Lettische Grammatik [Latvian Grammar] (1783), and two dictionaries – an appendix to the first grammar (1761), as well as the extensive Lettisches Lexicon (1789), Stender laid the foundation for a description of the Latvian language for the next hundred years. Not only did Old Stender himself become well known, but Stender's grammar and dictionary also became icons, familiar to those who love the Latvian language until the late 19th century.

Actually, the first dictionaries and grammars for the Latvian language had already been created by 17th-century authors – Georg Mancelius’ German-Latvian dictionary Lettus (1638), Johann Georg Rehehusen's grammar Manuductio (1644) and, of course, Heinrich Adolphi's grammar Erster Versuch [First Attempt] (1685). But time had passed, these publications were practically unavailable, and they were also outdated. The expectations as well as the achievements had moved on.

As an active and creative representative of the Enlightenment, Old Stender followed the latest developments in science closely and made use of them in his work.

This is evident in the introduction to the grammar (the second one, in particular), which explores questions of the linguistic affinities of the Latvian language, which had not been done previously. An interest in and an understanding of linguistic affinities in Europe increased in the 18th century, with comparative historical linguistics emerging in the early 19th century.

Naturally, Stender's notes are still a testimony to the thinking of that time, uncovering many interesting observations. Stender begins the introduction to his grammar by stating that "the Latvian language is a sister language of the Lithuanian language" and goes on to explain the origins of these languages. He considers Latvian to belong to the Slavic languages, which he justifies by comparing Latvian and Russian words. In his introduction, Stenders also draws attention to the links between Latvian and other languages.

He also points out that Latvian and Estonian are not interrelated, but that a language similar to Estonian is spoken by the so-called Kreevins (‘krieviņi’) in Kurzeme (the Province of Courland), near Bauska, and Livs. It is worth noting that Stenders considers Latvian to be one of the oldest European languages, as it contains many words that resemble the sounds of nature.

The chapter on grammar, devoted to dialects is the first extensive survey of the various territorial and social dialects of the Latvian language. In addition to examples of the languages of Augšzeme (Eastern Latvia) and Kurzeme, urban and written jargon is also mentioned, which is saturated with various unnecessary borrowings and semantic and syntactic calques. Stender urges that neither should these words nor local vernaculars should be used in proper language.

A separate chapter is devoted to the lexicon of the Latvian language. Stender describes both general aspects of the Latvian lexicon, such as the lack of words relating to culture, the emergence of new loanwords, the large vocabulary of words used in daily life, and some specific areas of the lexicon: philosophical terms, synonyms, homonyms, the mismatch between German and Latvian meanings of words, and swear words in Latvian. It also includes Latvian names of calendar months, a small collection of riddles, proverbs and some other material.

The chapter "on poetry" discusses Latvian folk songs and gives some examples. It also looks at Latvian poetry by German authors, mentions Christoph Fürecker and Johann Wischmann, and discusses issues of rhythm and rhyme.

Stender did not simply write a grammar of the language with word declension paradigms and simple models of syntax. Language reflects the history of a people, its soul, which is why Stender's grammar is much more than just a description of language.

Arturs Ozols, a researcher of the history of the written Latvian language, once described it as "[the] first single-authored collection of philological articles on Latvian orthography, grammar, lexis, phraseology, semantics, translation theory, ethnography, folklore, metrics and stylistics."

Stender's dictionary Lettisches Lexicon (1789) is another step forward in description of the Latvian language. The Latvian-German section contains about 7,000 words, and the German-Latvian section about 14,000 words. Following the main text in both sections, there are separate lists of person’s names, place names in Livland and Courland, names of animals, birds, fish, insects, trees, plants and mushrooms. Stender collected the dictionary material both from the living language and from dictionaries published by Kaspar Elvers (1748) and Jakob Lange (1772–1777).

Along with the work of Lange, Stenders' dictionary was the most valuable achievement of 18th-century Latvian lexicography, serving as a source of Latvian language for many people both in the late 18th century and in the first half of the 19th century. It was not until 1872 that two dictionaries (by Krišjānis Valdemārs and Kārlis Kristiāns Ulmanis) surpassed the work of Stenders.

Opening the first meeting of the Society of Latvian Friends in 1827, Christian Brockhusen, the pastor of Ikšķile, described him with the following words:

"...no one before his time has taken up [researching] the Latvian language so deeply, has studied it so much, and no one has been found to be wiser than him on the laws of the language and what can be learnt, so to speak, so that to this day his book of teaching the language which bears his name are still the writings from which we have all been learning and are still learning."