More about the cycle of events can be discovered at https://www.gramatai500.lv/ and for more about the Latvian National Library and its constantly changing exhibitions and collections, visit: https://www.lnb.lv/.

500 Years of Latvian Books: Would Duchess Dorothea of Courland have sung in Latvian?

David Hartmann's elegy and 12 songs with words by Eliza von der Recke, translated by Gotthard Friedrich Stender at the end of the 18th century could well be the first texts intended for solo singing in Latvian. Who was the addressee of these songs, and could a collection of songs in Latvian stimulate the Duchess of Courland's interest in social problems?

The Duchy of Courland, in full the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia (1561–1795), was located in the Baltic region, in the territory of present-day Latvia. Today, the former duchy forms one of the ethnographic regions of Latvia. In the 18th century, the Duchy of Courland was still a vassal state of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, but in actual fact it was Protestant German-dominated territory.

The Germans had settled in Courland during the Crusades and had gradually established themselves in this area since the 13th century, forming the uppper class of society and the educated middle class, while the Latvians remained mostly peasants, or worked as craftsmen and servants in the towns. During the Reformation, when churches were established on the basis of the spoken language, local or Baltic Germans – Protestant pastors – developed the Latvian written language and published the first religious books in Latvian. Church services in Latvian were conducted mainly by German pastors even up until the early 20th century. In the 18th century, serfdom was already established in the Baltics.

Karl Feierabend, a home tutor and later teacher in Danzig (now Gdańsk), writes about life in Courland in the 18th century:

"Courland is a wonderful land; the blessed prosperity is abundantly put to use. People and animals can live here and be happy! Everything that provides man's livelihood, that can contribute to his contentment, that can strengthen his domestic and civic well-being, all this was provided to this land by nature. Its fields burst with abundance; its seeds germinate, flourish and produce plenty of fruit; its forests yield timber and game. Oh, how many happy people could live here! But this abundance, this blessing, serves only a few, only a handful of people, for whom this has been their birthright by chance, and it is delightful to be in the presence of this handful of people for whom chance prevailed and their birthright ensured belonging to the nobility. (...) A peasant from Courland is a serf, subject to his lord with one’s body and one’s life [1]."

The Duchy of Courland and its capital Jelgava (Mitau) can be described as an insignificant province in the context of 18th century Europe, at the same time not denying its outstanding achievements in education, science and art, especially in the second half of the century. This was mainly due to the strong connections of the local Germans with Western Europe and their ability to attract young people, full of ideas, to the new, modern educational institution in the duchy, Academia Petrina (founded in 1775).

Describing the life of the Baltic Germans in Jelgava at this time, historian Erich Donnert wrote: "more often than not, their apartments were decorated with mirrors, paintings and tasteful furniture, the garments worn by the women and their adult daughters were fashionable, the food served was delicious, and their lifestyle was cultured. The music and dance evenings they held on festive occasions and weekends were well reputed [2].”

According to the 1797 census, Kurzeme had 416 960 inhabitants, 5.2% of whom lived in towns; 87.6% were Latvians, 86.2% of them serfs. Germans made up 8.27% of the total population of Kurzeme [3].

Gotthard Friedrich Stender, enlightenment of the people and songs in "folk style"

As a result of cultural transmission, the ideas of Popular Enlightenment [4] entered the Baltic region. German pastors laid the foundations for didactic secular literature, songs, fables and stories, books of advice, as well as the first periodicals and calendars, and ensured that the peasants gained an education.

Born into the family of a pastor from Courland, Gotthard Friedrich Stender (1714–1796) became very proficient in the Latvian language. According to Stender's contemporary Friedrich August Czarnewsky (c. 1766–1832), Stender "was very eager to converse with Latvians, and sought their love and trust. With a noteboard in his hand, he always noted down every unusual word or any word he had not heard previously" [5]. From 1759 to 1764, Stender lived abroad – in the Duchy of Braunschweig, also in Hamburg and Denmark.

During this time, he published a grammar and dictionary of the Latvian language in the Orphanage Press in Braunschweig [6]. The book concluded with a selection of modern German poetry in Latvian with several examples of odes and poems by Barthold Heinrich Brockes (1680–1747), and fables and pastoral lyrics by Christian Fürchtegott Gellert (1715–1769). The final poem of the selection depicts, with sentimental melancholy, the condition of the peasant under serfdom [7].

In his book Latvian Grammar, not only did Stender focus on the history of the language and its structure, but also on Latvian culture, including folk songs, for example by describing in detail the way songs are performed and the joy of singing them: "their singing is such that several girls sing together and some of them only sing o! in the same key, as if it were the bass, from which the whole neighbourhood often resounds. We Germans will never be as happy as the Latvians with their songs, especially where eating and drinking are in full swing." [8]

Stender also touched briefly on socio-economic contexts in the book on Grammar, pointing out that Latvians lack, for example, truly witty songs, but this is not the fault of the language, but of the current lack of culture due to serfdom. [9] The German scholar Wolfgang Schmid dubbed Stender's Grammar a political pamphlet [10]. However, Stender was not a social rights activist. After five years spent living abroad, he returned to Courland and continued his pastoral work in a rural parish. Like all pastors in Courland, being directly dependent on the local nobility and the Lutheran Church of the Duchy of Courland, Stender devoted his later life to the serene work of a good shepherd.

Hoping for financial support from the nobility, and in line with the ideas of the Enlightenment, Stender chose literary pursuits and the promotion of peasant schools among the nobility as a means of improving the conditions of the peasant population.

Although Stender's efforts were not entirely unsuccessful – a few peasant schools were indeed opened at his initiative – his urging did not achieve any greater success.

Nevertheless, Stender published the first collection of fables and stories in Latvian [11]; the first popular science book [12] and also secular songs [13]. In addition to folk songs, Latvians at this time were already singing songs taken from the manor repertoire, but with German melodies.

In 1774, Stender published his collection "Jaunas ziņģes pēc jaukām meldeijām par gudru izlustēšanu" [New songs with lovely melodies for wise enjoyment], which contained well-known German songs with pastoral, nature and love motifs and with reference to German melodies. The collection was soon reprinted (1783, 1789). In these later publications, the earlier references to melodies in German were now translated into Latvian, which could mean that the songs were already familiar among the singers. With these collections, Stender came close to the tradition of the so-called “Lieder im Volkston”, or "folk style songs", although Stender himself never used this term. Stender's songs remained popular well into the 19th century, some of them folklorised and were included in Latvian song collections.

Duchess Dorothea of Courland, her half-sister Elise von der Recke, music and Latvians

The Duchess of Courland and Semigallia, Anna Charlotte Dorothea von Medem (married name Biron, 1761–1821), came from a highly educated German aristocratic family. Her family friend, the German poet Christoph August Tiedge (1752–1841), later wrote: "The Count [Dorothea's father] loved music, and his wife enjoyed music equally as much. Moments of relaxation with music and dancing were interspersed with other festive occasions at home, which were further enhanced by the poetic talents of the Countess" [14].

Dorothea was also musically gifted: "During the next winter holidays in Jelgava, the young eight-year-old Dorothea, with her expertise already well-trained, wanted to perform a piano concert for the court" [15]. A few years later Dorothea began to take part in concerts and plays at the Duke's palace: "The Duke had a comfortable theatre built in his palace. Dorothea von Medem was not to be absent from them; here, too, she excelled with her thespian talents, with the splendid sound of her voice and the artistry of her singing in the best opera productions" [16].

Dorothea von Medem's half-sister Elisabeth Charlotte Constance von Medem, later known as Elisa von der Recke (1754–1833), is considered one of the greatest women of the Baltic Enlightenment period – a sentimental poet, author of travel notes, who also gained attention in Europe for her memoir exposé from the time she met the charlatan, adventurer and mystic, Count Alessandro di Cagliostro (1743–1795), a practitioner of the occult arts [17]. Her article was translated into Russian (1787) and later into Swedish (1793) and widely discussed. The Russian Tsarina Catherine the Great who was delighted with her talents even leased the Glūda Estate (German: Pfalzgrafen) in Courland to Recke. Her sacred poetry gained a growing number of admirers, especially among German composers of the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, and many compositions featured her poetry.

In total, around a hundred songs with words by von der Recke have survived to the present day in both published and manuscript format, among them are compositions by Johann Adam Hiller (1728–1804), Johann Gottlieb Naumann (1741–1801), Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (1745–1814), Johann Abraham Peter Schulz (1747–1800) and Friedrich Heinrich Himmel (1745–1814). [18] Von der Recke travelled frequently and also visited Dresden. In 1784, during a trip to Carlsbad, von der Recke met Johann Gottlieb Naumann in Dresden and they became good friends. After Naumann's death, Recke became his first biographer and an active promoter of his talent in German periodicals and culture.

Naumann's close friend, the German composer Adam Hiller not only composed, but also arranged a collection of songs by Elisa von der Recke during a visit to the Duke of Courland's home. [19] Von der Recke's half-sister, now the beautiful young wife of Duke Peter von Biron (1724–1800), also attracted attention in the educated German society in Europe. She not only attended concerts with great enthusiasm, but also played music herself. They both strengthened the link between German society in Western Europe and the Baltic region.

For example, Elisa von der Recke, enthusiastic about the poetry of the late Gottlob David Hartmann (1752–1775), a professor at Peter's Academy in Jelgava, recited it in Dresden to Johann Gottlieb Naumann. The poem "Sophron an seine Freunde” [Sophron to his friends] was composed on Elisa's suggestion. In 1785, Hartmann's elegy was published in a separate edition with the complete melody by Johann Gottlieb Naumann. [20] The poem – and the song – are a striking example of sentimentalist culture. It reveals an endless mourning for unfulfilled love and ends with suicidal ideation. The poem's mood echoes the motif of young Werther's suffering in the German poet Johann Wolfgang Goethe's youthful composition Die Leiden des Jungen Werthers [The Sorrows of Young Werther] (1774).

Reading the poem and discussing its meaning and content became a fashionable pastime in German society. Hartmann's biography reveals that the interest in sad, unrequited love was not simply one of many themes that aroused Hartmann's interest. Born near Ludwigsburg in Baden-Württemberg, he graduated from the local convent school, studied at the University of Tübingen, developed a passion for Horace, wrote poetry and received his Doctorate of Philosophy from the University of Erfurt in 1773. In 1774, at the invitation of the Duke of Courland, Hartmann came to Jelgava to work as a Professor of Philosophy at Peter's Academy.

During this period, he met the well-educated Elisa von der Recke, and reading and discussing the latest literary news the time passed without the two of them noticing. They also shared a passion for the works of young Goethe, especially The Sorrows of Young Werther, which brought the two even closer together.[21]

Unfortunately, suddenly struck down with fever and, according to other sources, due to an unrequited love for von der Recke, Hartmann died at the age of 23 in Jelgava and was buried in the Trinity Church. The melancholic mood of "Sofron to his friends", written by Hartmann and composed by Naumann is also enhanced by the choice of musical instruments – piano and con sordino violin, as well as by the reference on the title page to “Für Wenige”, or `for the few’.

In 1787 Naumann published a collection of 12 songs with words by Elisa von der Recke for solo piano accompaniment, XII. von Elisens geistlichen Liedern beym Clavier zu singen [Twelve of Elisa’s Spiritual Songs, to be sung with piano accompaniment]. Naumann dedicated the collection to von der Recke's half-sister, Duchess Dorothea of Courland. Unfortunately, I have not been able to find any record of Dorothea singing these songs by Naumann.

Elisa von der Recke was not only a gifted writer, but like Catherine II and other enlightened ladies of her time, she was also concerned with social issues and the fate of the Latvians of Courland. This is evidenced by her correspondence with the Baltic German enlightener Garlieb Helwig Merkel (1769–1850), in which von der Recke advocated the liberation of the peasants from serfdom. [22]

Merkel called on Elisa von der Recke to free the peasants on her property. She chose to live and work within the framework of her order and position, without taking any radical steps. The fact that this topic played such a prominent role in the correspondence between Merkel and von der Recke is in itself remarkable. Duchess Dorothea also thought about the Latvians, as revealed in the biography of her contemporary, the German poet Tiedge, for example, when she went to Rome and mentioned the bloody process of Christianisation of the Latvians in the Middle Ages [23]. Serfdom was abolished in Courland and Livland (now Vidzeme) in 1817 and 1819 respectively, giving peasants freedom of movement but not property rights. The land remained German property, and colonial relations persisted.

Translations of German solo songs into Latvian

In 1784, Gotthard Friedrich Stender translated the previously mentioned song "Sophron an seine Freunde" [Sophron to his friends] by David Hartmann into Latvian. It does not belong to the genre of “Lieder im Volkston”, or folk style songs. The complex form of the poem, in which each of the four lines of the verse has its own number of syllables, with the literary translator requiring an excellent knowledge of the language.

Stender generally pays great attention to the form, but there are lines which deviate from the original number of syllables and stresses. In the translation, the melancholy mood of the poem is complemented by diminutives and a sense of piety. As the letter f was not yet in the Latvian alphabet in the 18th century, Stender transformed the name of the title character Sophron (pronounced Sofron) into the well-known Latvian word ‘Sprancis'.

Stender's translation attracted the attention of the local German public. With no reference to the translator, Hartmann's poem was already published in 1784 in German and Latvian in a local Courland newspaper [24], soon followed by a similar publication in the Deutsches Museum [25] in Leipzig. Stender himself apparently found the form of Hartmann's poem sufficiently complex, yet also interesting, for him to imitate it in his tribute to his relatives.

The second part of the collection Ziņģu Lustes was the publication of his own song “Augsta Siņģe saweem Behrneem und Behrnu-behrneem” [High song for my children and children’s children] [26]. Stender was aware of his advanced age and contemplated his imminent death and the separation from his beloved children and grandchildren in a philosophical, elegiac mood. Stender added a note to his composition that it was to be sung to the melody of Hartmann's song, most likely composed by Naumann.

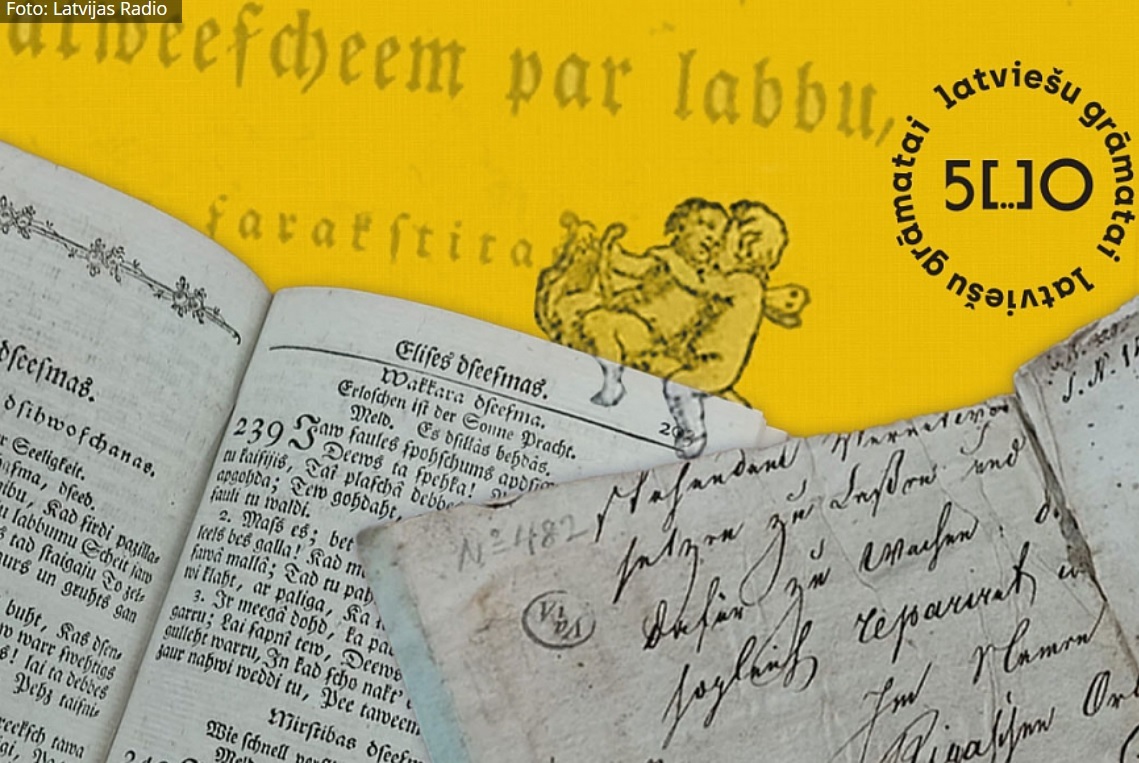

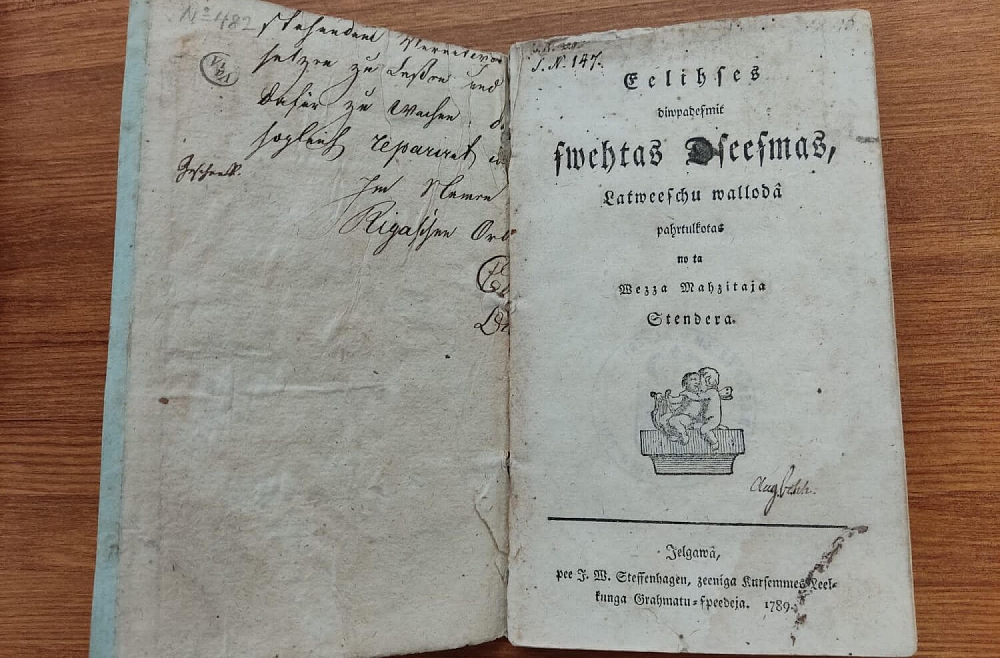

'Elisa's twelve sacred hymns translated into Latvian by that old pastor Stender'

In 1789, Stender translated into Latvian a collection of hymns titled XII. von Elisens geistlichen Liedern beym Clavier zu singen [XII. of Elisa’s sacred songs to be sung at the piano], compiled by Elisa von der Recke and composed by Naumann [27]. Unlike the original, he did not publish it with the sheet music, but a comparison of the translated and original texts reveals, in most cases, an exact correspondence between the number of syllables and the rhyme scheme of the original.

Stender also dedicated his translation to the Duchess of Courland, Dorothea, thus paving the way for the Latvian language to reach the Duke’s court: "Tas gaischums, kas eeksch Eelihses swehtahm Dseesmahm walda, un muhsu Tehwu-semmei gohdu darra, irr wissu mannu dwehseli ar swehtu ugguni pildījis, tahs paschas Latwiski isdarrinaht. Kam warru es schihs swehtas Dseesmas labbaki nodoht, kà tahm mihligahm un schehligahm Rohkahm muhsu Wissmihlakas Semmes/Mahtes, which it Latweeschu tautu ne smahde, bet ar tahs semniskâ wallodâ daschu reis schehligi sarunnatees ne atraujahs" [The light that dominates Elisa’s sacred songs and celebrates our Fatherland, has filled the whole of my soul with the sacred fire to translate these songs into Latvian. Whom I can bestow these holy songs on as not on those loving and gracious hands of our Dearest Mother Earth, who does not spurn the Latvian people, but holds a few gracious conversations with them in their native language] [28].

Not a single word in the book’s introduction suggested that the addressee of the collection might be the Latvians.

Short letters of thanks to Stender for the collection from both Duchess Dorothea and Elisa von der Recke have survived. They were peppered with courteous phrases befitting the style of the time. [29] Dorothea's promise to try to live up to Stender's expectations can also be seen as a courtesy [30]. That same year, the Baltic German newspaper Mitauische Zeitung also published a short review of Stender's translations of von der Recke's songs. The review, however, does not mention the dedication to Dorothea, nor is the fact that Stender actually translated the solo songs for singing at the piano, but Latvians are identified as the main addressees [31].

Hartmann's translation of the elegy, as well as Elisa von der Recke's collection of twelve songs may be the first texts intended for solo singing in Latvian. A few years later, another Courland pastor, Johann Christoph Baumbach (1742–1801) translated twenty-one of Elisa von der Recke's songs into Latvian, compiled and published these translations in a hymnal, Holy Songs (1796).

'Sacred Songs'

Although von der Recke's translations of the songs are published in a separate appendix, there is no indication in the book that they are intended for solo singing; quite the opposite. All the texts are accompanied by the German melodies of traditional sacred songs.

It is possible that with his translations Baumbach simply wanted to diversify the repertoire for congregational singing. Irmgarde Schettler, a scholar of German sacred hymns points out that the hymns of Elisa von der Recke could be regarded as paraphrases of the Courland hymn writer Christoph Friedrich Neander and other Courland German sacred hymn writers, which were in turn also written as paraphrases of well-known Lutheran hymns [32].

Since Baumbach’s translations of von der Recke's songs were accompanied by the well-known German melodies mentioned above, it would probably not have been difficult for the Latvian congregations to learn the new texts as well. We have no information about the inclusion of von der Recke's songs in the singing repertoire of Latvian congregations.

On the hypothetical addressee of the first Latvian solo songs

Gotthard Friedrich Stender's translation of Hartmann's elegy and twelve spiritual songs by Elisa von der Recke raises the question: who was the true addressee? Could Duchess Dorothea have sung these songs with piano accompaniment in Latvian? Or could Latvians have sung for Duchess Dorothea in their own language? There are no records of Naumann's songs being performed in Latvian in the 18th century, but we can hypothetically assume that such possibilities existed.

Research today shows that Latvian was, indeed, spoken in German social circles in Courland. Firstly, of course, it was used to communicate with the Latvians. It should also be taken into account that Baltic German families traditionally had Latvian wet nurses and nannies; a large proportion of Germans in Courland spoke Latvian, at least in their childhood [33].

As evidenced by 17th-century occasional poetry in Latvian and the memories of Baltic Germans and their contemporaries [34],Latvian was often used as the language of the region and used as a unifying regional language for the Germans of Courland to separate them, for example, from the Germans of Prussia. The motto of Curonia, the German Students' Association of Courland – TDD – means "Tam Draugam Draugs" [Friend of that friend] in Latvian [35]. This language was also used when Baltic Germans wished to keep something confidential from the German circles of Western Europe. Duchess Dorothea also used Latvian to communicate with her husband in such situations [36].

In theory, Dorothea could have sung in Latvian

It is also possible that when he was dedicating the collection to Dorothea, Stender had Latvians in mind as an addressee. However, the serious, religious-philosophical orientation of the songs casts doubt on this. The repertoire of songs sung during house devotions and also during church services was limited. The supply of hymn books far surpassed demand. Not only Latvians, but pastors also were slow to decide on new texts. The reformed neologist hymnbooks of the early 19th century caused an uproar in Latvian congregations, demanding a return to the old traditional ones. There is also no evidence that the hymns of Elisa von der Recke were sung by Latvians.

Perhaps Stender's target audience was Latvian musicians at the Duke’s court and in the manors? Latvian solo singers at the piano of the Duke? This possibility is, of course, not entirely out of the question. Latvians played in German orchestras, Latvian choirs sang at festivals of the nobility, Latvians were the opening singers in churches, but there are no records of solo singing in manors, let alone at court. The word piano, although a popular instrument in local German society, gradually gained its importance in Latvian culture from the third decade of the 19th century onwards – after the abolition of serfdom – as a part of the interior of some homes of educated Latvians and of the wealthier Latvian schools [37].

It is possible that with Elisa von der Recke's songs in Latvian, Stender wanted to diversify the repertoire of German youth in Courland, who were probably already singing Stender's German songs in Latvian. This is indirectly implied by a review published in the press following the publication of another work by G. F. Stender, The Book of High Wisdom. [38]

However, one would like to believe that Stender's Latvian translation of Elisa von der Recke's highly praised poem by Hartmann, just like von der Recke's translations of spiritual songs, should first of all be seen as a lovely gesture to remind us that Latvian can also be the language of modern culture, and therefore that Latvians, although they were serfs at that time, have a great potential for modern culture and therefore also for freedom. It seems that Elisa von der Recke's interest in social issues did not go unnoticed by Stender.

And who else but Dorothea von Biron, with von der Recke's support, could have directly contributed to a change in the fate of Latvians, perhaps even contributing to their liberation from serfdom.

Can a collection of songs in Latvian stimulate the Duchess of Courland's interest in social problems? This is an open question.

NOTES

[1] "Kurland ist ein herrliches Land; die Fülle des Segens ist überall reichlich ausgegossen. Menschen und Vieh können leben und glücklich sein! Was zum Unterhalt des Menschen dient, was seine Zufriedenheit befördern, sein häusliches und bürgerliches Wohlsein befestigen kann, das alles hat die Natur diesem Lande geschenkt. Seine Äcker triefen von Segen; seine Saaten gedeihen und bringen vielfältige Frucht, seine Waldungen spenden Holz und Wild in Überfluß.… O wie viele glückliche Menschen könnten hier wohnen! Aber dieser Überfluß, dieser Segen dient nur Wenigen und schönt nur für die Handvoll Menschen da zu sein, denen Zufall und Geburt die Herrschaft gab.… Der kurländsiche Bauer ist völlig leibeigen und seinem Herrn mit Leib und Leben unterworfen." Cited by: Erich Donnert, Kurland im Ideenbereich der Französischen Revolution: Politische Bewegungen und gesellschaftliche Erneuerungsversuche 1789–1795 (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 1992), S.26 [if there are no other references mentioned, all translations are mine – MG.].

[2] "Überdies waren deren Wohnungen in den meisten Fällen mit Spiegeln, Bildern und Möbeln ausgestattet, die Kleidung der Frauen und erwachsenen Töchter modern gehalten, die aufgetragenen Speisen schmackhaft und die Lebensführung kultiviert. In gutem Ruf standen die gelegentlich von Festen und Feiertagen veranstalteten Musik- und Tanzabende." Donnert, Kurland im Ideenbereich, S. 31.

[3] Donnert, Kurland im Ideenbereich, 26.

[4] Cf. Pauls Daija, Literary History and Popular Enlightenment in Latvian Culture (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2017); Māra Grudule, "Volksaufklärung in Lettland," in Die Entdeckung von Volk, Erziehung und Ökonomie im europäischen Netzwerk der Aufklärung, ed. Hanno Schmitt et al. (Bremen: Edition Lumière, 2011), S.137−157.

[5] [Friedrich August Czarnewsky], Stenders Leben nebst Anmerkungen und Beilagen (Mitau: J. F. Steffenhagen und Sohn, 1805), S.17−18.

[6] Gotthard Friedrich Stender, Neue vollständigere Lettische Grammatik Nebst einem hinlänglichen Lexicon (Braunschweig: Fürstliches-großes Weisenhaus, 1761).

[7] Nabags zemnieks Kurzemnieks, / Cik tev goda, kāds tev prieks? / Sausu maizi paēdi, / Ūdens malku nodzēri, / Darbi pillam, miega maz, / Dūmi izgrauž actiņas, / Pātags kapā pakaļu, / Rīkstes brīžam muguru, / Tomēr esi nebēdnieks, / Nabags zemnieks Kurzemnieks. In: XVIII Der Curische Bauer. Neue vollständigere, S.220.

[8] Ihre vollständigste Vocal-Music besteht darin, wenn eine Parthey Mädgens zusammen singen, und ein Theil darunter blos das O! Aus einem Ton weg einstimmet, als welches gleichsam den Baß vorstellet, wovon oftmals die ganze Gegend erschallet. Nimmer mehr werden wir Deutschen bey der schönsten Music so vergnügt seyn, als die Letten bey ihren Liedern, zumal wo Fressen und Saufen vollauf ist. In: Neue vollständigere, 1761, S. 152-153.

[9] Daß in den meisten Bauerliedern nicht eben viel witziges anzutreffen, daran ist nicht ihre Sprache selbst, sondern der Mangel der Cultur, wegen der Leibeigenschaft, darin sie stehen, schuld. In: Neue vollständigere, 1761, S. 153

[10] Schmid, W.P. Gotthard Friedrich Stender (1714-1796) und die Entwicklung der lettischen Schriftsprache. In: Kulturgeschichte der baltischen Länder in der Frühen Neuzeit mit einem Ausblick in die Moderne. Garber, K., Klöker, M. (Hrsgs.). Tübingen: Max Niemeyer, 2003, S. 227.

[11] Jaukas pasakas in stāsti tiem latviešiem par gudru mācību. Jelgava: Lītke, 1766

[12] Augstas gudrības grāmata no pasaules dabas. Jelgava un Aizpute: Hincs, 1774.

[13] Jaunas ziņģes pēc jaukām meldeijām par gudru izlustēšanu. Jelgava un Aizpute: Hincs, 1774.

[14] "Der Graf liebte die Tonkunst; nicht weniger Freude an ihr fand seine Gattin. Musikalische Unterhaltungen und Tanz wechselten mit andern häuslichen Festen, welche durch die dichterische Erfindungsgabe der Gräfin verherrlichet wurden." Christoph August Tiedge, Anna Charlotta Dorothea, letzte Herzogin von Kurland (Leipzig: F. A. Brockhaus, 1823), 12.

[15] "Bei dem nächsten Winteraufenthalt in Mitau vermochte die achtjährige Dorothea schon mit geübten Kräften sich in einem Hofconcert auf dem Fortepiano hören zu lassen." Tiedge, Anna Charlotta Dorothea, 24.

[16] "Er ließ im Schlosse ein wohl eingerichtetes Theater bauen. Es wurden Opern und andre Schauspiele aufgeführt.… Hier durfte Dorothea von Medem nicht fehlen; sie errang auch hier wiederum durch ihre Darstellungsgabe im Schauspiel, durch die Trefflichkeit ihrer Stimme und durch die Kunstfertigkeit ihres Gesanges in der Oper den höchsten Preis." Tiedge, Anna Charlotta Dorothea, 30.

[17] Elisa von der Recke, Nachricht von des berüchtigten Cagliostro Aufenthalt in Mitau im Jahre 1779 und dessen magischen Operationen (Berlin: Nikolai, 1787).

[18] Kornél Magvas, ""Unvermerkt entfloh’n unsre Stunden von fünf Uhr Abends bis gegen Mitternacht bei Orpheus Naumann.": Elisa von der Reckes Beziehung zu Johann Gottlieb Naumann und zeitgenössische Vertonungen ihrer Gedichte," in Elisa von der Recke: Aufklärerische Kontexte und lebensweltliche Perpektiven, ed. Valérie Leyh et al. (Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag, 2018), 196.

[19] Joh. Adam Hillers geistliche Lieder einer vornehmen kurländischen Dame, mit Melodien (Leipzig, 1780); Elisens geistliche Gedichte, nebst einem Oratorium und einer Hymne von C. F. Neander, ed. Johann Adam Hiller, (Leipzig, 1783).

[20] Johann Gottlieb Naumann, Elegie von Hartmann: für Wenige (Dresden: Hilscher, 1785); https://imslp.org/wiki/Elegie_(Naumann_Johann_Gottlieb).

[21] Otto Harnack, "Werther in Kurland," in Baltische Monatschrift 35 (1888): S. 515–521.

[22] "Garlieb Helwig Merkel an Elisa von der Recke, 20. Juli 1797," in Garlieb Helwig Merkel, Briefwechsel, ed. Dirk Sangmeister with Thomas Taterka and Jörg Drews (Bremen: edition lumière, 2019), 1:26−27.

[23] Tiedge, Anna Charlotta Dorothea, 82.

[24] "Spranzis," in Mitauische Monatschrift, March 1784, 284−285.

[25] "Auszug eines Briefs von Hn. Prof. Jäger aus Mitau vom 18.Apr.84 an Hn. Schulmeister Hartmann in Ludwigsburg." Deutsches Museum 43, no. 2 (1784), 90.

[26] "Augsta Siņģe us saweem Behrneem un Behrnu-behrneem". In: Siņģu Lustes Ohtra, S.52. The poem was originally composed in German (1787), later it was partially translated into Latvian. Stender dedicated the poem to his family and their meeting in 1786 with Eva Elisabeth von Schwentzen (1745-1794), when she came from Copenhagen to Courland to visit her father G.F. Stender. More about this: Kārlis Kundziņš: Wezais Stenders sawâ dsihwê un darbâ. Jelgava 1879, S. 94-97.

[27] Eelihses diwpadesmit swehtas Dseesmas

[28] [Elisa von der Recke]: Eelihses diwpadesmit swehtas Dseesmas, Latweeschu wallodâ pahrtulkotas no ta Wezza Mahzitaja Stendera. Jelgava 1789, S. [4].

[29] Cf. Czarnewsky, Stenders Leben, S. 103−104.

[30] Streben will ich, das zu verdienen, was Sie, verehrungswerther Mann, über mich sagen und so, theurer Herr Präpositus, bin ich mit wahrem Gefühle Ihres Verdienstes Ihre Sie schätzende Dorothea, Herzogin zu Kurland. In: Czarnewsky, Stenders Leben, S. 103.

[31] Cf. Anzeige. Mitauische Zeitungen, Nr. 19 (6.03.1789).

[32] Irmgard Scheitler, "Elisa von der Reckes Geistliche Lieder und ihre Vertonung durch Johann Adam Hiller," in: Elisa von der Recke: Aufklärerische Kontexte und lebensweltliche Perpektiven, ed. Valérie Leyh et al. (Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag, 2018), S. 179–180.

[33] Cf. Ulrike Plath. Esten und Deutsche in den baltischen Provinzen Russlands. Fremdheitskonstruktionen, Lebenswelten, Kolonialphantasien 1750-1850. Wiesbaden: Harrasowitz Verlag, 2011, S.193.

[34] Cf. Kundziņš, Kārlis. Kārlis Hugenbergers: latviešu tautas draugs un dziesminieks. [Rīga: Zīslaks, 1890], p. 6. etc.

[35] Cf. Sietiņsons, A. Curonia's 150 gadi. Universitas, 1958, Nr. 5, 60.–63.lpp.

[36] Cf. Louise de Prusse. Quarante-cinque années de ma vie (1770-1815). Paris, 1911, 32.

[37] It is mentioned for the first time in Latvian in the German-Latvian part of G.F.Stender's dictionary:"Clavier, klaweere, tahs leelas stihgu spehles [Piano, piano, a big instrument with strings]," cited by: Gotthard Friedrich Stender, Lettisches Lexicon. In zween Theilen. Deutschlettisches Wörter-Lexicon (Mitau 1789) S. 66.

[38] Cf. "Gelehrte Sachen: Augstas Gudribas Grahmata no Pasaules un Dabbas: Sarakstita no Sehlpilles un Sunakstes Basnizkunga Stender. Jelgawâ un Aisputte, pee J. F. Hinz 1774." Mitauische Politische und gelehrte Zeitungen no. 7 (25 July 1775): 27.