More about the cycle of events can be discovered at https://www.gramatai500.lv/ and for more about the Latvian National Library and its constantly changing exhibitions and collections, visit: https://www.lnb.lv/.

A witty man and a Latvian hero – who was Garlieb Merkel?

Although one of Riga's central streets is named after Garlieb Merkel, Merkel himself and his works, just like the Baltic Age of Enlightenment as a whole are unknown to a large part of society. Because their education was gained during the Soviet era, for the middle and older generations Merkel's name is probably associated with his essay Latvieši [Latvians] and the abolition of serfdom. For most young people, Merkel most likely means the name of a street. And that is all.

At the same time, it must also be acknowledged that researching the Age of Enlightenment, incl. the study of Merkel's work and personality continues to expand in breadth and depth among a small circle of scholars in Latvia and abroad. In recent decades, not only have individual scholarly articles devoted to Merkel appeared in Germany, but also new editions of his works [1]. Also in Riga, marking the occasion of the 250th anniversary of the birth of Merkel in 2019, the National Library of Latvia hosted an exhibition dedicated to Merkel, created by Dr. philol. Aija Taimiņa. An international scientific conference, which brought together Enlightenment scholars from Germany, Poland, Estonia and Latvia was also held at the same venue. Time has passed and the exhibition catalogue [2] and a collection of articles have been published that are dedicated to the persona, works and era of Garlībs Merķelis (his name in its Latvian form) [3].

In order for these publications to attract wider public interest, perhaps the general public should first be reminded who Garlieb Merkel was? And why Merkel Street? Hence what follows next is about Garlieb Merkel.

A glimpse into Merkel's life

Garlieb Helwig Merkel (1769–1850) was born in Lēdurga (Loddiger) into a pastor’s family. The Merkel family had ties with the Baltics since the end of the 17th century – in 1689 a newcomer from Saxony, Andreas Merkel, a turner and member of the Great Guild was registered in Cēsis [4]. Garlieb Merkel was born into a family of eight children. His father, Daniel Merkel (1712–1782), had been married three times. All of his children, except the eldest daughter, were Garlieb Merkel's full siblings. Daniel Merkel was dismissed from the pastorate of Lēdurga for poor performance of his duties and became the assistant pastor of Vecpiebalga. He died when Garlieb was thirteen years old [5]. After the death of his father, the family was in financial difficulties and young Merkel was forced to leave school. However, his inquisitive, persistent nature ensured a path of self-education, first in his father's library [6] and then among friends and acquaintances [7]. In 1785, a few years after his father's death, the family left Zādzene (Saadsen) estate which his father had rented and moved to Riga, where Merkel continued his studies, worked as a clerk, taught private lessons and worked as an extra in the German theatre in Riga. His work at the theatre opened the way for Merkel to join the German intelligentsia in Riga.

Witty, knowledgeable and inquisitive, he commanded attention with his independent judgements and skilful exchanges of ideas.

His years working as a private tutor in Liepupe (Pernigel) and Nītaure (Nitau) followed, and a short-term job in the Riga District Court Office. It was only at the turn of the century that he was able to continue his education in Germany – in Berlin and Frankfurt an der Oder, where Merkel gained a Doctorate in Philosophy. Unlike most Baltic Germans associated with Latvian culture, Merkel did not study theology and never worked as a pastor. After completing his studies and working as a journalist in Germany, he returned to the Baltics and mainly devoted himself to journalism. While in Germany, Merkel had already started covering the Napoleonic wars and political opinions on the war; he encouraged his compatriots to take a patriotic stand for the resistance.

After his return to the Baltics, he continued to denounce Napoleon's policies. When the French army invaded Russia, Merkel was so vehemently opposed to the occupation that he had to move temporarily to Dorpat (now Tartu) in the autumn of 1812[8]. According to sources, Marquis Filippo Paulucci (1779–1849), Governor-General of the Baltic provinces at that time, even compared Merkel's anti-Napoleonic journalistic contribution to an army of 20 000 men. Merkel spent 1816/1817 in Germany and returned to Riga via Lübeck in the spring of 1817 to continue his career as a publicist. Tsar Alexander I of Russia granted him a pension of 300 silver roubles for his essay "Free Latvians and Estonians" (1820). Merkel also supported the publication of the first bilingual Latvian and German edition of the novel Ciems, kur zeltu taisa [The Village Where Gold is Made] [9], which promoted the co-operative movement.

Merkel did not have a smooth relationship with the Baltic German community. Although the conservative Latvian Literary (Friends) Society admitted him as an honorary member in 1841, the question of his resignation was discussed almost simultaneously. During the last decades of his life, Merkel and his family lived in Depkina Manor, now Rāmava Manor (Rammenhof) near Riga. The manor was named after its long-time inhabitants, the Depkins – the pastor and also the landlord; it was a rectory with eight farmhouses. A drawing by Johann Christoph Brotze shows that in 1770 the manor complex consisted of ten buildings, a sauna, a vegetable plot and a pond.

Garlieb Merkel himself was also keen on farming [10]. In September 1807 he married Dorothea Wilhelmine Germann (1779–1853), the widow of Doctor Dorndorff; she was also the daughter of the sub-rector of the Riga Dome School. She had three children from her first marriage – two daughters and a son, and they also settled in Depkina Manor. After the death of Garlieb Merkel and his wife, it was one of his stepdaughters, Julia Dorndorff (1802–1890) who kept Merkel's memory alive and was the primary supporter of erecting the monument dedicated to him. Thirteen of his relatives attended the centenary of Garlieb Merkel and the unveiling of his tombstone in 1869, which was also mainly thanks to Julia Dorndorff [11].

Merkel himself had three children in his marriage to Dorothea Wilhelmine Dorndorff – Amalia, later her married name was Lehmann (1808–1887), the physician Dr. Ernst Merkel (1810–1863), who worked in Riga, and was a doctor in spa resorts in Dubulti and Ķemeri. He published theatre reviews and was active in journalism – he was editor of the Rigaischen Stadtblaetter and publisher of the Riga German trade newspaper and a member of the Society of Natural History Researchers. Ernst Merkel was married to Wilhemine Juliane Germann, the daughter of his mother's brother, the burgomaster of Riga at that time.

His marriage also produced eight children, seven daughters and a son; his great-uncle Garlieb Merkel was alive when the first five of his children were born. Garlieb Merkel's youngest son, Adolf (1813–1830) committed suicide and was buried in the Katlakalna cemetery [12]. In 1847, following several years of illness Garlieb Merkel was likely to have suffered a stroke, his eyesight rapidly deteriorated and his right arm was paralysed. He joined his youngest son in death in 1850 and was also buried in Katlakalna cemetery.

Merkel's views and how they developed

Several societies and the like-minded contemporaries he met there played an important role in shaping Merkel's views. In 1787, based on the model of English clubs, a society or club called "Musse", meaning one’s "free time", was founded in the German Theatre building in Riga where Merkel worked as an extra. Merkel met the German intelligentsia of Riga and spent time socialising at Musse. Merkel also became involved in the local German youth intellectual group, the Prophetenclub or the “Prophets’ Club” (1786–1796), where lively discussions on art, literature and philosophy [13] took place in a relaxed atmosphere, the members of which included liberal-minded actors, doctors, lawyers, pastors and publicists from Riga.

In 1786, for example, Merkel and his friend, the actor Karl Ferdinand Daniel Grohmann (1758–1794), had a passionate public exchange of ideas at the Prophets' Club, with both discussing the ideas of Schiller and Voltaire [14]. It is likely that the Freemasons also played an important role in Merkel's life; several of his acquaintances and friends in Riga were Freemasons, such as the theologian and later head of the Livland Church, Karl Gottlob Sonntag (1765–1827); one of the "prophets" of Riga, Georg Ludwig Collins (1763–1814), also belonged to this organisation.

As Aija Taimiņa points out, also in Berlin "Merkel's closest acquaintances were Freemasons – Christoph Martin Wieland (1733–1813), Carl August Böttiger (1760–1835), Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803). The Freemasonic network helped to solve many important questions" [15]. At first, Merkel joined the "Society of the Friends of Mankind", but soon after, on 18 February 1799 he was admitted to the Lodge named "Friedrich Wilhelm's Crowned Righteousness" where he became a Master. The Freemasonic organisations of the Enlightenment were characterised by democratic principles, and in the Baltic region this also meant advocating social justice and the abolition of serfdom.

Self-study in the private libraries of his father, friends and fellow thinkers, as well as studies at the elite Riga Dome School, and later studies in medicine, philosophy, history and aesthetics at various German universities, mainly in Berlin and Frankfurt an der Oder, all played an important role in the development of Merkel's views. Merkel spoke French, English, Italian and Latin, and it is likely that he had also learnt Latvian in his youth.

Merkel was greatly influenced by his friendship with Grohmann, an actor in the German theatre, Karl Grass (1767–1814), the son of a Livland pastor and his peer, and in Germany by his exchange of ideas with the cultural philosopher, Johann Gottfried Herder. Merkel's circle of acquaintances also included the German writers Johann Wolfgang Goethe (1749–1832), Friedrich Schiller (1759–1805) and Martin Wieland, as well as philosopher Johann Gottlob Fichte (1762–1814), who, incidentally, was accepted into the Freemasons in 1800 on Merkel's recommendation.

Garlieb Merkel is known in the German cultural sphere as a literary critic and publicist. A little more about this period in his life (1796–1806) – Merkel left the Baltics to publish the harshly critical essay Die Letten, vorzüglich in Liefland am Ende des philosophischen Jahrhunderts (The Latvians, primarily in Livland, at the End of the Philosophic Century, 1796/97).

Following its widespread publicity it was clear that he could not return to Livland. In 1797, Merkel briefly stayed in Copenhagen, Denmark, and was private secretary to Heinrich Ernst von Schimmelmann (1747–1831), Minister of Finance. He then worked as a journalist and for a time as a lecturer at the University of Frankfurt an der Oder, where he taught a course in aesthetics. The family of Johann Gottfried Herder urged Merkel not to give up his lectureship, saying that it was good for developing thinking and gaining experience. However, Merkel was more interested in writing and journalism. He wrote manuscripts on Latvian cultural history – the sentimental romantic tale Wannem Ymanta and the essay Die Vorzeit Lieflands [Livland in Antiquity].

Merkel himself considered Voltaire, Marie-Henri Beyle (Stendahl), Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Montesquieu, Moore, Hobbes and Herder to be his most like-minded philosophers, and among the Baltic Germans – the enlighteners Johann Georg Eisen (1717–1779) and August Wilhelm Hupel (1737–1819). Merkel was also fascinated by the ideas of Hume and translated the works of Hume and Rousseau into German.

Merkel in literary criticism

A series of articles of literary criticism, Briefe an ein Frauenzimmer (Letters to a Woman, 1800–1803), appeared as a small magazine-type publication during his German period. It comprised around 300 articles. The addressee of the letters was Sophie, wife of the Berlin bookseller and merchant Sander, and the letters themselves were written as a spiritual duel with the Romantic author August Schlegel (1767–1845), who had taken a liking to Sophie.

Merkel's great merit as a publicist was the creation of the German feuilleton genre.

Merkel also freely polemicised with his prominent contemporaries – Herder, Goethe, Schiller, Wieland, Lessing, Novalis and even Kant. He railed against German conservatism and a Classical zeal for the past. Merkel believed that Lessing was superior to the Schlegels because the latter led away from the life of the nation and its issues into a world of blind fantasy, mystified situations and dreams. He also criticised Schiller's Wallenstein for its lack of truthfulness [16]. He had no doubt that for this reason the public would soon lose interest in Schiller's drama.

Romantic mystifications are superfluous, they only create superstitious premonitions in the spectator [17]. Merkel also criticised Goethe's works. He also criticised the fragile Baltic German writer Casimir Ulrich Boehlendorff (1775–1825) [18]. The German literary scholar and Boehlendorff researcher Eva Zimmermann argues that Merkel's dislike of Boehlendorff had deeper roots stemming from their collegial relationship [19].

According to Merkel, all of the arts activate the mind, but literature and theatre are the most powerful of them: words have power, but theatre can activate the mind and the senses. The ideal creator of art is a genius, endowed with the sublime and the beautiful.

If with Die Letten Merkel made enemies among the local nobility, then – as Ojārs Zanders points out – with Briefe he made enemies in German-speaking Europe [20]. Merkel was considered old-fashioned. This is probably why today some German encyclopaedias hardly mention Merkel, and if they do, only as an opponent of Goethe, Schiller and German Romanticism. During his lifetime, Merkel already earned such labels as "shallow-headed", "a shabby, banal, bland critic", "one of those many yapping enemies who are not even worth replying to" – for example, Goethe wrote some juicy "invectives" (invectiva oratio – "hate speech") against Merkel [21].

In Weimar, Merkel became acquainted with the Herder family. He made use of the Herder family’s library, received material support and became part of the Weimar intellectuals. Herder wrote good reviews of Merkel's works, promoted an interest in Die Letten and highly rated his work The Works of Hume and Rousseau on the Primitive Treaty, together with an Essay on Serfdom (1797). He reviewed Merkel in Erfurter Nachrichten (1797) and, in fact, with Herder's recommendation, Merkel was able to go to Copenhagen. Herder's wife also played an important role in the relationship between Herder's family and Merkel. The two continued to correspond after Herder's death in 1803.

The Academic Library of the University of Latvia (UL) has preserved 14 of Caroline Herder’s letters (1801–1804). During the time when Merkel had already fallen from favour among German writers, she stressed that the door of the Herder house was always open to Merkel because "we are older, more tolerant, calmer" [22].

With his writing, Merkel was unexpectedly versatile, he was interested in philosophy, sociology, politics, including the abolition of serfdom, as well as history, law, literature and aesthetics. The range of periodicals that Merkel edited and which published his writing is also unusually broad, e.g. the monthly journal-type publication Briefe an ein Frauenzimmer [Letters to a Ladies’ Court] (Berlin-Leipzig, 1800–1803); Ernst und Scherz [Seriously and Jokingly] (Berlin, 1803–04; 1816–1817); together with the playwright and publicist August von Kotzebue, Merkel was editor of the magazine Der Freimütige [The Outspoken Ones] in Berlin (1804–06) and its sequel Supplementblätter zum Freimütige [Supplementary Pages to the Outspoken Ones], published in Riga (1807). Also published in Riga were the journal Der Zuschauer [The Spectator] (1807–1831) and Zeitung für Literatur und Kunst [Newspaper for Literature and Art] (1811/12), a newspaper devoted specifically to art and literature, as well as Glossen [Glossary] (1813, Riga) and four issues of Livländische Merkur [Livonian Mercury] (1818). After the death of Karl Gottlob Sonntag, Merkel took over the Livland newspaper Ostseeprovinzenblatt [Baltic Provincial Gazette] (1827–1828), changed its name to Provinzialblatt für Kur- Liv und Ehstland [Provincial Gazette for Courland, Livland and Estonia] and continued to be its editor until his death.

Pēteris Zeile, who compiled Merkel's cultural and historical articles, is of the opinion, that he is the founder of a new type of journalism in the Baltics and Germany, as "his writing synthesises journalism, Enlightenment philosophy and cultural essays which could be likened to a form of the arts" [23].

Merkel on the Latvians

Merkel's merits are linked to his historical approach in his writing on the Baltic region – he also takes into account the rights of Estonians and Latvians when assessing the history of the Baltic region and has a complex view of historical events. At the same time, he is limited in his assessment of Latvians and Estonians within the narrow confines of the peasant class. Merkel's main publications on the history and social situation of the indigenous peoples of Livland were written at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries. Later, after serfdom was abolished in the Baltics, Merkel considers the social question to have been solved.

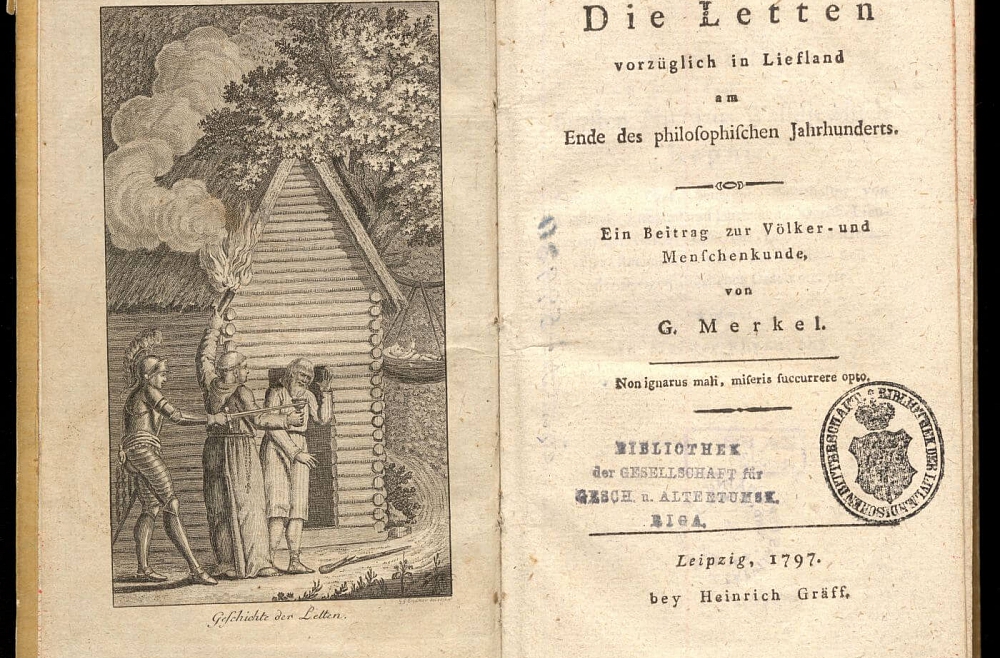

Garlieb Merkel. Latvians, Mostly in Livland, at the End of the Philosophical Century. A Contribution to the Study of Nations and Peoples, 1797.

Merkel's journalistic work Latvians, Mostly in Livland, at the End of the Philosophical Century (1796/97) was written and published in German in Leipzig. It was primarily written at Annas Manor (Ermes-Neuhof), while Merkel was working there as a home tutor. Die Letten contains material that Merkel learnt as a child from observing his father in the rural parishes of Livland, as well as literature that Merkel read in the libraries of friends and acquaintances, and in Riga while working as a court clerk. The addressee of Die Letten was the German-speaking community of Europe. Merkel also wanted to gain international support for the abolition of serfdom in the Baltics. Die Letten contained a sharp critique of the German upper class in Livland, with an exaggerated depiction of peasant life in the Livland countryside in the second half of the 18th century.

The data obtained at the Court Office led Merkel to make broad generalisations, justifying through individual cases the general degradation of the Latvians – drinking, immorality, thievery, lying and humility.

The work resonated widely among the Baltic German upper class. A few years later, in response to criticism, Merkel produced a new, extended edition of Die Letten and a supplement Supplement zu den Letten [Supplement to the Latvians] (1798); in 1800 another extended edition of Die Letten was published with the essay "Interrogation of the peasants of Livland in court, testifying against their baron".

As Gvido Straube points out, Merkel's Die Letten should not be seen as an unexpected phenomenon, but as a typical publication of its time, representing the efforts of one particular sector of society to transform society in the spirit of the ideas of the Enlightenment, i.e. to democratise, grant equality, the rule of law, freedom and education." [24].

In 1804, a second edition of the work was published; unlike before, times had changed, and the book was more fiercely attacked by his contemporaries. Several noblemen published harsh, even hostile, articles opposing him, while at the same time Merkel also had supporters among the Baltic nobility, such as Eliza von der Recke (1754–1833), the educated half-sister of Duchess Dorothea of Courland. Although there is evidence that Die Letten was also read in 19th century Latvian society, Merkel's work was translated into Latvian relatively late – only in 1905. Although it has been reprinted many times, there is no complete translation of it to date.

Several other works devoted to Latvians appeared in 1797: in the newspaper Der Deutsche Merkur [The German Mercury], edited by Martin Wieland, Merkel published essays entitled “Sitten Lieflands aus der Ersten Hälfte des 16. Jahrhunderts” [The Virtues of Livland in the First Half of the 16th Century] and “Über Dichtergeist und Dichtung des Letten” [On the Poetic Spirit and Poetry of the Latvians) [25].

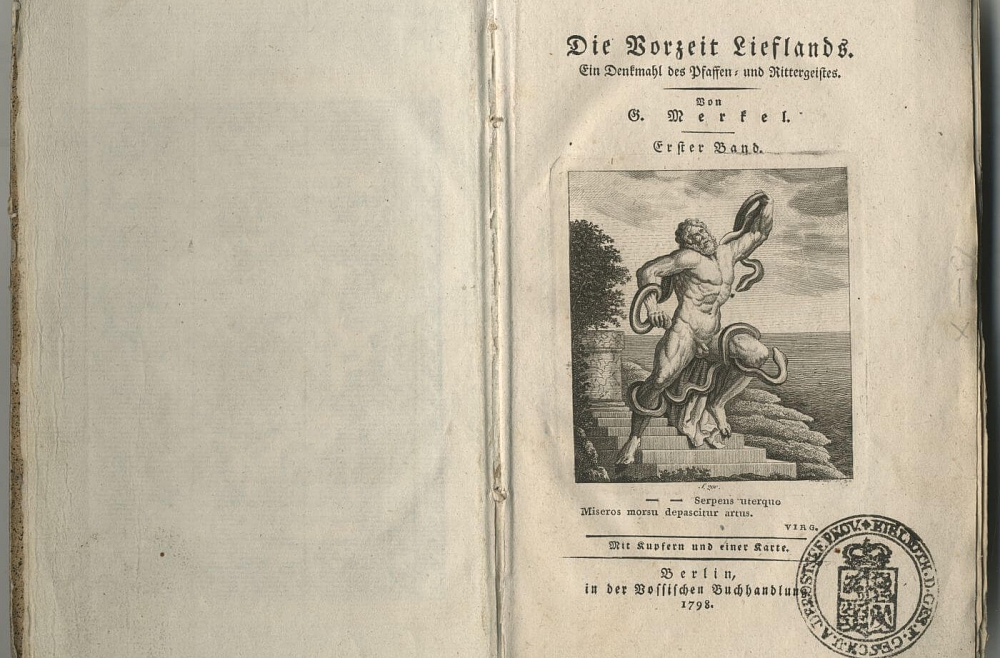

Die Vorzeit Lieflands [Livland in Antiquity] (1798, 1799) is a two-volume study of the history of the Latvian people. It was also translated into Latvian much later – in 1906 by Matīss Kaudzīte (1848–1926). When writing Die Vorzeit Lieflands, Merkel studied various sources – chronicles, works by Paul Einhorn (1590–1655) and Tacitus, made use of materials on the Baltics available in libraries in Copenhagen, Dresden, Weimar and elsewhere. Merkel believed that the southeastern region of Europe was the ancestral homeland of the Latvians. Just like his contemporaries, he linked Latvian antiquity to Prussia as the ancestral homeland and described Latvian songs of lament, Līgo, the god of love and joy and Videvud, the creator of the Latvian people, etc. Antons Birkerts has already pointed out that Merkel was faced with a lack of material when he wrote Vidzemes senatne [26].

Merkel himself pointed this out, admitting that the book is only an attempt to describe the past of Livland, including mainly Latvian cultural history (Merkel did not use the term 'cultural history' yet), describing the ancient Latvian spiritual world, virtues, customs, everyday life, etc., which is why the term "antiquity" is used, not "history". It is possible that he based the arrangement of content and materials on J.G. Herder's ideas on history as a science, especially in Ideas for the Philosophy of the History of Mankind (1784).

For Merkel, there were generally only two periods: the period before the Crusades, up to the 13th century, and the 18th century. Merkel probably only came across folklore indirectly. Beata Paškevica has researched that, for example, the article “On the Poetic Spirit and Poetry of the Latvians" uses G.F. Stender's Grammar of the Latvian Language (1789) [27]. Merkel described folk songs and their genres, for instance, songs with serious content; cheerful songs; funeral and wedding laments; songs of praise to deities; and festive songs sung during the seasonal customs, stressing that they are primarily two- and four- liners, depicting everyday situations, based on improvisation, with women as the main singers.

Merkel's own experiences were probably integrated into his insights into the Latvian way of life and material culture. Merkel was also familiar with fables, stories, proverbs and sayings, the sources of which are still to be found. Descriptions of Latvians are much better developed in Die Vorzeit Lieflands than those of the Estonians and Livs; for example, only one Estonian folk song is quoted from the material already published by Herder. Looking back at Latvian mythology, Merkel described the main deities and the possible origins of ancient beliefs.

Merkel was the first to use folklore as a reflection of life and beliefs and a counterpart of history in order to praise Latvian antiquity.

A few years later, Merkel's sentimental romantic tale, Wannem Ymanta (1802) was published. The origin of its protagonist, Imanta, was probably connected with the school drama titled Albert or the Founding of Riga, written by the Riga Dome School teacher Johann Gotthelf Lindner (1729–1776). The source of the story is the Livonian Chronicle (in which Imants kills Bishop Berthold in 1198). However, there are slight differences, e.g. in Lindner's play Imants dies at the hands of Aco, not Kaupo.

The two works share a dream in which Imants sees the future history of the Latvians, the conquest and complete subjugation of Livland, and its liberation, as it becomes a part of the Russian Empire and the granting of freedom to the peasants by Tsar Alexander the Great. In Lindner's play, Imants, as if in a trance, sees Aco perish and Riga crumble. Lindner's play was performed in November 1760 by pupils of the Dome School. Merkel's knowledge of Lindner's work is demonstrated by his own anonymously published article on examinations at the Dome School (cf. Provinzialblatt für Kur-, Liv- und Estland, 1836, 9.VII.).

In any case, the 13th-century chronicles were a popular source of Baltic German literature in the 18th and 19th centuries. For example, in his collection Kuronia (1791), Karl August Küttner (1749–1800) writes about the antiquity of Courland and also equates Latvian antiquity with Prussian antiquity; Küttner's poetry “Svētceļojums uz Rāmavu” [Pilgrimage to Rāmava], "Piltenes burvju bungas" [The Magical Drums of Piltene] and "Kaupo, dižciltīgais Turaidas lībietis" [Kaupo, the noble Liv of Turaida] all featured in the collection. Merkel may have read this work too – his scene on Zilais kalns is quite similar to the same scene in Küttner 's poem about Kaupo.

If Lindner juxtaposes Kaupo with Aco, then Küttner does this with Viesturs, and Merkel with Imanta. The general mood of Wannem Ymanta is probably inspired by the folk tales heard in Liepupe and observations of Līgo festival celebrations [28]. According to Merkel, his original intention was to present a Latvian hero in epic song, unlamented and unrecognised, haunted by a long night, but he later abandoned this, creating, as he claims, simple poetic prose, because he had political cosmopolitan goals in mind, as evidenced by the dream in which Catherine the Great, Stephen Bathory and Gustavus Adolphus all appear: "I wanted to revive empathy for the sad fate of these peoples, I wanted to give their oppressors a warning in a new format about their attitudes and actions; – finally, above all, I wanted to send out a loud cry to that throne from which such great and varied benefaction is now coming over Russia. [...] I know that this is a very well-intentioned patriotic act" [29].

With Grand Duchess Anna as the mediator, the book reached the Tsar who gave Merkel a gold ring.

The myth of Merkel and its perception in Latvian society and culture

Although Latvians were no strangers to Merkel's ideas already during his lifetime, as attested by the manuscript literature [30] , these were only isolated cases.

Merkel became a Latvian "national hero" or a person of cultural and historical significance, a person who could almost be placed in the Latvian pantheon during the National Awakening in the second half of the 19th century, when, thinking about the celebration of Merkel’s centenary, the New Latvians raised the idea of building a monument on the site of Merkel’s grave.

This required funds. The campaign was actually started in 1868 by New Latvian Rihards Tomsons (1834–1893). Addressing his compatriots at the Riga Latvian Society, he allegedly showed a portrait of Merkel to those present and learnt that no one knew who the man was. This was followed by a short description by Tomsons of his works and merits and a boat trip to Katlakalna cemetery to find that Merkel's grave had been neglected. The Riga Latvian Society therefore started promoting Merkel in the Latvian press and raising money for a monument [31].

The revitalising of Merkel among the Latvian people began with the celebration of his centenary in 1869. The literary scholar Ojārs Lāms writes: "We could say that there is nothing accidental in the structure of this celebration; all the events are based on mythical notions, thus trying to link what is in the depths of the psyche with the actual development of the times. Merkel has the honour of initiating the iconography of Latvian national ideology, as Merkel's engraving is printed and distributed for donations to raise funds for the tombstone. (...) Merkel acquires lasting epithets and designations – freedom fighter, Latvian apostle of freedom, etc. Merkel's grave in Katlakalns (..) becomes a symbolic place. The process of reviving Merkel's memory is like an archaic mythical ritual." [32] The journey to Merkel's grave continues as a ritual throughout the second half of the 19th century.

The earliest references to Merkel in Latvian are associated with the manuscript literature of Livland. J. Pulans has retold the content of Latvieši and Vidzemes senatne, also interspersing in his text fragments from G. F. Stender's Augstas gudrības grāmata [Book of High Wisdom], facts about knightly orders and the Crusades in Palestine, episodes from 13th century Latvian history and the legend of Wilhelm Tell [33]. The manuscript was written between 1810 and 1820 with the undeniable spirit that serfdom will be abolished. It has 25 chapters, with fragments of Merkel's Die Letten included in the opening and closing sections, and Die Vorzeit Lieflands included in the middle section.

In total, Merkel's works comprise about 75% of the text. Pulans has omitted Merkel’s general opinions, philosophical and economic justification of the criticism of serfdom, facts about the cultures of other nationalities, a depiction of the quarrels of the occupants, references to historical sources, but has supplemented the text with his own observations. Book historian Aleksejs Apīnis thinks that Pulans' work can be considered an independent work of political journalism, characterised by artistic thinking, and it is the first review of Latvian history written by a Latvian. Copies of Pulans' work have survived [34].

Merkel’s influence can also be felt in Jānis Ruģēns' (1817–1876) essay "The path to the Livland sky seen with one’s own eyes", written in 1843 and first published in Ruģēns' collected works (1939), but until then it was read in several different copies. The first comprehensive biography of Merkel with an analysis of his works, "Dr. Merķeļa mūža strauts” [The Stream of Dr. Merkel’s Life] was written by primary school teacher Friedrich Mahlberg (1824–1907) around 1850 or 1851. Juris Alunāns (1832–1864) tried to publish it, but the censorship commission in Dorpat (Tartu) did not allow it to be published. Friedrich Mahlberg's manuscript was first published in 1934 [35] with a brief commentary by Žanis Unāms (1902–1989). The manuscript was found in Fricis Brīvzemnieks’ (1846–1907) archives; there is no information on how it got there, but it is now kept in the Misiņa Library of the Academic Library of the University of Latvia. It is likely that Mahlberg also used Merkel's autobiography Darstellungen und Characteristen aus meinem Leben, 1839 [Descriptions and characters from my life, 1839]. Merkel, his era and ideas were also embodied in literary visions by other Latvian cultural figures, playwrights and prose writers throughout the 20th century, such as Rainis, Saulcerīte Viese, Marģeris Zariņš, Māra Zālīte, Aivars Kļavis and others [36].