The nomination

Unofficial nominations begin months before the parliamentary vote. Candidates officially get chosen by parties, but large interest groups and civic movements usually express their support for certain candidates. Parties often put their most well-known and famous candidates in the spotlight for the election, trying to gain popular support for their nominees. Interparty alliances are also formed to to gain support from the members of the parliament, and, as the director of the Centre for Public Policy “Providus” Iveta Kažoka establishes, “party alliances have more power when deciding the outcome of the election than campaign promises made before the election.”

For example, in the 1999 election, a parliamentary gridlock occurred – no candidate could collect the vital 51 votes in order to become the president. After five rounds of voting, an unlikely candidate emerged – a Latvian emigre from Canada named Vaira Vīķe-Freiberga – as a compromise between Latvia’s largest political parties looking to limit the opposition’s influence. As a result, she was elected in the second round of voting by 53 votes.

In the 2011 election, Andris Bērziņš’ emergence as the winner was a surprise to many, even his own party members. Bērziņš was deemed as a virtually unknown candidate and his election was thought of as an unlikely event. Despite that, he was elected in the second round of voting and assumed office on July 8.

The voting process

According to the Latvian Presidential Election Law, the Presidium of the Saeima calls for a parliamentary session no earlier than 40, but no later than 30 days before the end of the term of the incumbent president. Members of the Saeima then vote for the desired candidate. If no candidate receives a simple majority of all votes, then members move to vote again in the second round. If no one gets elected then, the candidate with least votes gets eliminated during each round until one nominee remains. If so, they must collect 50+1 votes to become the president-elect. Saeima can reschedule the election if the remaining candidate fails to get a simple majority of all votes.

Sometimes elections have yielded unexpected results. In the 2011 presidential vote, many members of the Saeima took photos of their ballots to prove to journalists that they had really voted for the candidate they initially sought to. Nevertheless inconsistencies between the choices of the deputies obtained during interviews with journalists and the actual outcome of the vote have often been at variance – a major flaw in the secret ballot system.

President in Latvia vs. presidents elsewhere: what's the difference?

Latvia is not a presidential republic – the president gets elected by the parliament, not by the people or an electoral college. The president is head of state and acts as a symbolic and representative figure. He or she is also the nominal commander-in-chief of the armed forces.

What can the president do?

Presidents in Latvia can sign bills into laws, ratify treaties, issue pardons, and declare war (with a Saeima vote). They also choose the head of the government, call for special parliamentary sessions, as well as have the right to dissolve the parliament and call an early election. Each president acts as a representative of Latvia abroad, appoints ambassadors, and receives foreign diplomats.

How will this year’s election be different?

In the 2019 election, a new constitutional amendment will change the voting process in the parliament. The very recently introduced open ballot system will hold members of the Saeima accountable for their vote for presidential nominees and will try to raise people’s trust in the parliamentary system by providing for more transparency.

History of presidential elections in Latvia

After gaining independence in 1918, many politicians were initially opposed to establishing the position of president at all, in fear of concentrating too much power in one person’s hands.

The next concern was the actual elections. People argued that Latvians were a “politically unstable” nation and populism could spread easily. Therefore, the Saeima should deal with the matter in a less fervid atmosphere.

The parliamentary process remained relatively uninterrupted up until 1934 when, during a coup led by the former prime minister Kārlis Ulmanis, the parliament was dissolved and Ulmanis declared himself both the State President and the Prime Minister. His coup was based on the belief that the parliamentary system was ineffective and the government was unstable.

Since the restoration of independence in 1991, the Saeima has tried to deescalate any conflicts between the executive and legislative branches of the government by avoiding concentrating too much power in too few hands and providing for more transparency in the government through various legislative means.

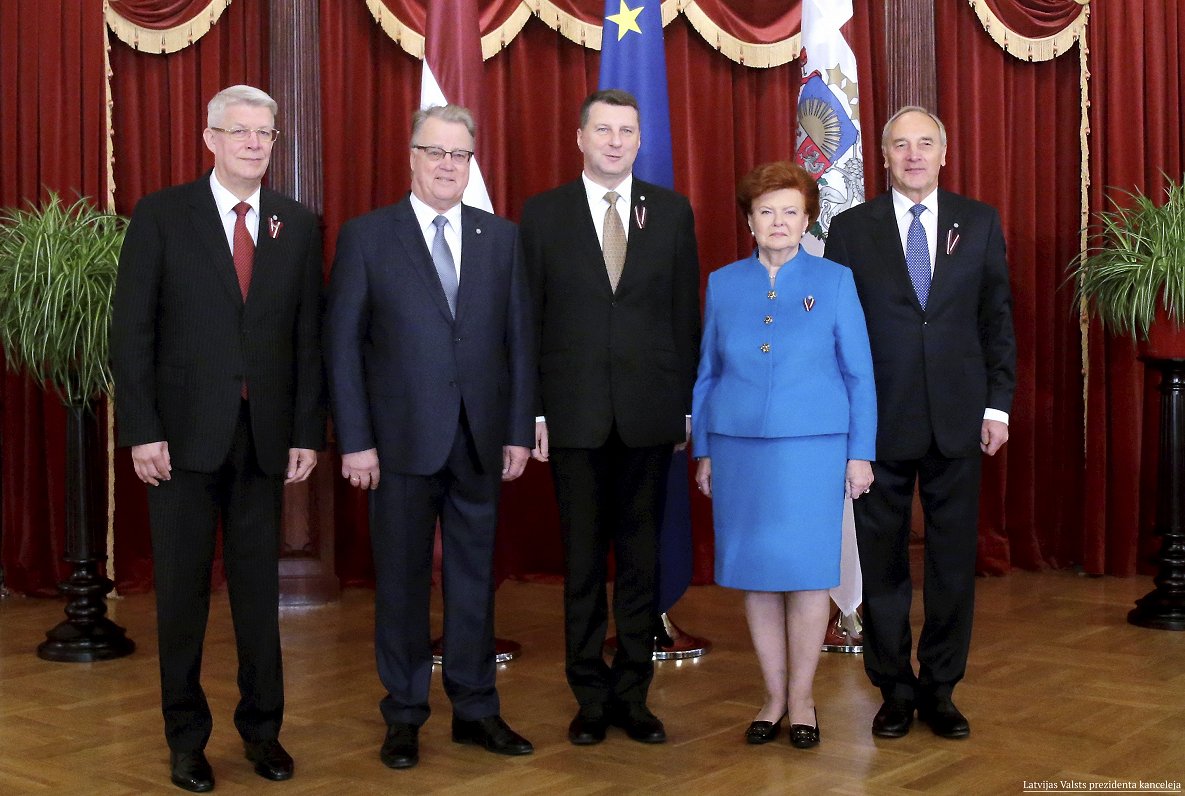

List of post-1991 presidents in Latvia

Guntis Ulmanis (president from 1993 until 1999) – actively shaped Latvia’s foreign policy after regaining independence in 1991 and oversaw the Russian army’s withdrawal from the country

Vaira Vīķe-Freiberga (president from 1999 until 2007) – first woman president of Latvia; during her tenure, Latvia became a member of both the European Union and NATO

Valdis Zatlers (president from 2007 until 2011) – first post-independence president to use the executive power to dissolve the Saeima and call for an early election

Andris Bērziņš (president from 2011 until 2015) – while in office, he tried to amend the constitution to increase presidential power and strengthen the executive branch of the government

Raimonds Vējonis (president from 2015 until June 2019) – Vējonis emphasized the importance of the establishment of the Young Guard – a patriotic youth organization, and was named one of Europe’s “greenest” presidents for his active involvement in environmental politics

More information on the institution of the presidency and previous presidents is available at the official website of the State President.