Clearly, any story which is patently false, is blatant propaganda, has no credible source, or is just very badly written, is not something a news outlet should publish.

On the morning of April 23, LSM English received an unsolicited email from "Edgars Palladis", the text of which went:

Dear Editor,

I am a blogger from Latvia where Canadian military personnel deployed.

About 20 Canadian soldiers have tested positive for the coronavirus. It was confirmed by the commander of the multi-nation battle group Lt-Col Eric Angell (LINK TO PORTAL PROVIDED). But our government keeps silence and do not provide them medical personnel and necessary equipment.

The battlegroup led by Canada, operating with Latvian forces in Adazi, continue fulfilling their duties, also military training, including exercises planned at the range.

Canadian soldiers need help and there are a lot of comments in social media but no help. I hope you to publish this information. Thanks a lot.

Best wishes and stay healthy!

Edgars Palladis from Latvia

It took something between 1 and 2 seconds to decide this was a load of horse***t. First, the name did not sound credible. You don't tend to get double-L words in Latvian names. I've never heard the name 'Palladis' before. It sounds almost like a failed anagram of "Paldies".

A couple of clicks was all it took to reinforce the certainty that this source, and consequently its information, was indeed horse***t. The link provided led to an amateurish news portal, devoid of contact details, and in which all the half-dozen equally poor contributions submitted by Mr. Palladis during the last month suggest NATO is an aggressive military conspiracy bent on doing down plucky Russia.

Several other contributors are familiar names to anyone who regularly has to weed out rubbishy conspiracy-theory type content.

On YouTube, Mr. Palladis has but one video. It is quite recent and uses the well-known but eye-rollingly obvious and childish technique of intercutting footage of whoever you don't like with footage of marching Nazis. In this case the equivalence is between NATO and the Nazis.

But the most eye-catching thing about the fake news website is that while it may lack editorial details it has an online store generously stocked with pro-Putin "magic mugs".

To put it mildly, this is not a credible news outlet, and had it not been for Mr Palladis' email we would never have been aware of its benighted existence. It would have been nuts to publish such a 'story'.

By the afternoon however, the existence of this drivel had come to the attention of the NATO Strategic Communications Center of Excellence. Its director, Jānis Sārts, tweeted a live link to the story along with the comment that it represented part of an "uptick of Covid related disinformation in the Baltics", presumably referring to an even more gonzo story the day before from Lithuania.

We are recently experiencing uptick of Covid related disinformation in the Baltics targeting NATO eFP! https://t.co/CpuOJ04w1x

— Jānis Sārts (@janis_sarts) April 23, 2020

By the evening the Latvian Ministry of Defense was piling in with a counter-blast several times longer than the original fake news story and which added a whole new level of psychoanalysis to the narrative by talking about the inferiority complexes of "our adversaries". An official tweet ends with the Latvian presence in NATO apparently in Trumpian tweet mode voicing its opinion that a quote from its own defense minister is "Very TRUE!"

‼️ Latvian MOD @AizsardzibasMin dispels latest FAKE news on #COVID19 impact on @NATO & ?? Armed Forces. To quote defense minister @Pabriks "Such attempts to attack the information domain show that our adversaries suffer from a certain degree of inferiority complex."

— Latvia in NATO ?? (@LV_NATO) April 23, 2020

Very TRUE! https://t.co/nesVykfv7h

At this point the humble reporter is placed in a strange position. A news story that was horse***t and not worth reporting is now being commented on in a very serious way by influential public figures and officials with thousands of followers, who are even providing links to it.

And thus, whether we like it or not, it becomes newsworthy.

Having fulfilled the basic journalistic filtering process, that filter is now overwhelmed by these influential people stressing the importance of not disseminating fake news.

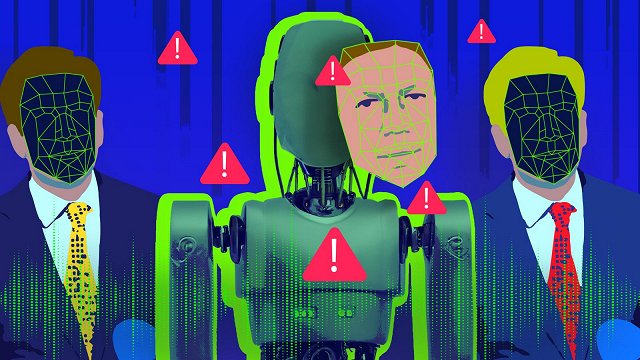

This brings us to an uncomfortable position. Usually, the assumed aim of fake news is to disseminate itself among sections of the public who are too credulous, misguided, or uneducated to know any better, in addition to people who have straightforward malicious intent. Based upon this, officials have a strong and legitimate argument that by making a big deal of fake news as early as possible, they might prevent it "gaining traction" among the public, on social media and so forth.

However, fake news source material may also achieve its spread not via public ignorance but thanks to the diligence, pride or even intellectual vanity of the people exposing it.

So we should be careful about thinking ourselves clever because we have identified a fake news story. Identifying such stories is usually child's play. Making too much out of the de-bunking process tends to elevate the importance of the original, obscure and inept source material.

An interesting debunk may prompt many more people to click on the original story than would otherwise have been the case. The sheer weight of official machinery brought against a silly story may even lend it a certain credibility among those predisposed to believe in conspiracy theories: "They would say that, wouldn't they? Why would they devote so much attention to it unless there was something in it?"

As far as the media is concerned, it's a Catch-22 situation. Help keep the information space clean by using good journalistic practice and not reporting fake news - unless the fake news has already been reported by credible sources as a means of keeping the information space clean.

Clearly a balance needs to be found in which it is possible to debunk such stories without making too much out of them. Groups like the Digital Forensic Research Lab and EU vs Disinfo are the best at this. Their tone is dispassionate and forensic, examining fake stories as if they are dissecting reasonably interesting insects to make a tiny contribution to a scientific catalog.

Yet at risk of ending on an inelegant note I cannot help but think that in general, the best way of pointing out horse***t, is simply to say: "This is horse***t," and leave it at that.