Readers, libraries and languages

During the century of Reformation, readers were polyglots with a wide range of interests. They were interested in the renewal of the church, travelers were interested in obtaining education and in their work, and European monarchs, Rīga's councilors (Ratsherren), the Dukes of Courland, Lutherans, Calvinists, Jesuits, as well as promoters of educational reforms and the typography tycoons and the shapers of local libraries.

The Reformation itself grew out from the experience of reading, i.e. Martin Luther's interpretation of St Paul's Epistle to the Romans. It provided the basis of what would become the Protestant doctrine, and Luther's own ideas spread further through the written word. For example, his To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation had a print run of 4,000. It was sold out within a couple of days and re-released thirteen times within two years.

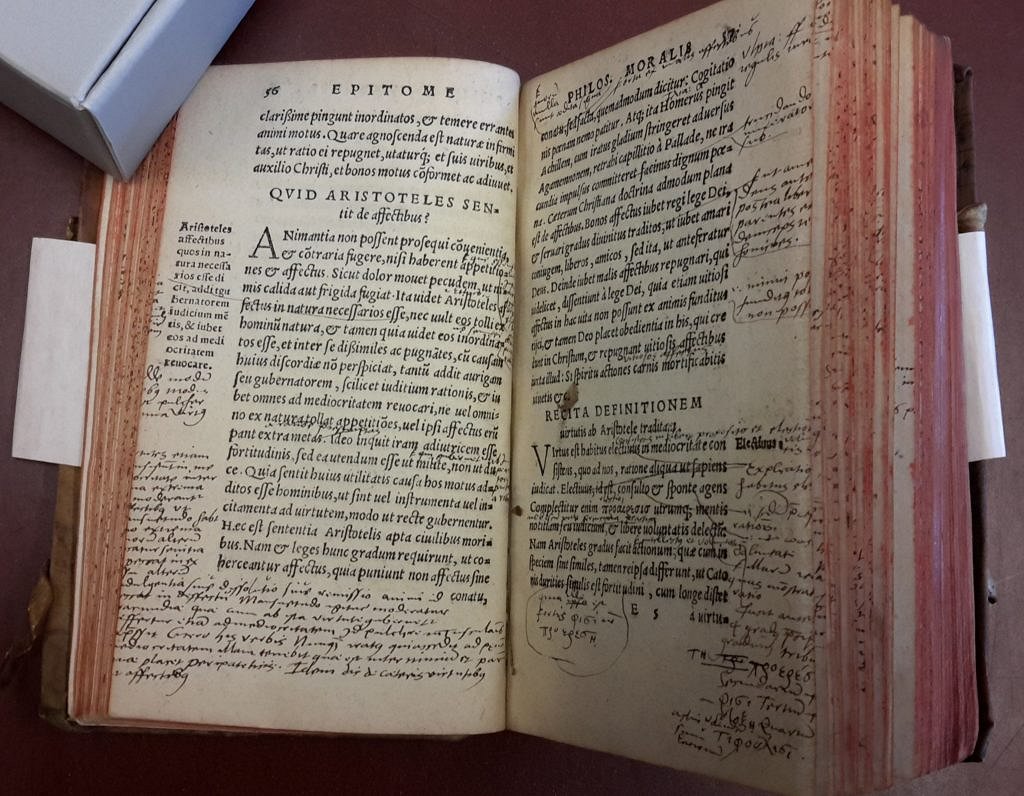

(Photo: The University of Latvia Academic Library: The New Testament, edited by M. Luther. Frankurt, 1554. The inscription G. T. M. L. – Gottes Tod – mein Leben, or God's death is my life. 1567. Laurentius Lemchen R.[igensis], a pastor in the city of Rīga, died 1611.)

Likewise in Rīga the Reformation started with a discussion, followed by the publication of Andreas Knöpken's In epistolam ad rhomanos Andreae Knopken costrinensis interpretatio, an interpretation of the Epistle to the Romans in 24 theses. It directed spiritual life in Livonia towards Protestantism and was reissued for another four times shortly after release.

However, even during the Reformation a great part of Europe's population didn't know how to read, and that's why church news were transmitted orally – through sermons, reading texts aloud and through singing.

The century of Reformation was an era when churches and monasteries were destroyed and books were burned. The oldest known book in Latvian – the agenda of a Protestant service – was likewise burned by Catholics in Lübeck. To preserve books, Martin Luther asked local government heads to set up libraries. The German historian Klaus Garber wrote aptly that, as ships take refuge in ports during a storm, so the books that survived were preserved in libraries and later on became available to the public at large.

At about the same time as in Magdeburg, Hamburg, Augsburg, and Nuremberg, Rīga's first public library was set up in the first half of the 16th century. A document referring to this says: "In 1524, about mid-lent, I, Nicolaus Ramme, received the following books from the Gray Monastery that were handed to me by the honorable, wise and prudent [Rīga's] Bürgermeister Paul Dreiling, so that they were put to use and served the common good." Out of the five books, four are preserved to this day. They now make up the earliest collection, age-wise, of the University of Latvia Academic Library. In the mid-16th century the collection grew larger thanks to donations by Rīga citizens.

Perhaps one of the greatest home libraries of that time belonged to the German diplomat and poet, Daniel Hermann (c. 1543–1601), who moved to Rīga in the latter half of his life. Hermanis, the former secretary at the Imperial Court in Vienna, then the city secretary of Danzig and the a representative at the Polish Royal Court, arrived in Rīga on March 1, 1582 shortly before the visit of Polish king Stephen Báthory. He found love in Rīga and settled down permanently. As of now, 32 books have been identified as part of the collection that was bequeathed to the City Library after his death. Some of them were bought, others were given to him and several have valuable notes penned by his contemporaries.

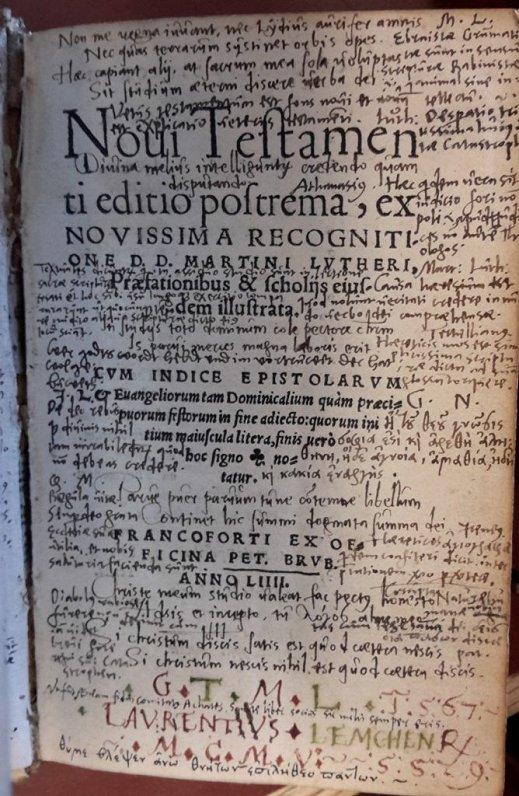

(Photo: University of Tartu Library. The title page of Daniel Hermann's collected writings.)

A few words about books and technology in the 16th century

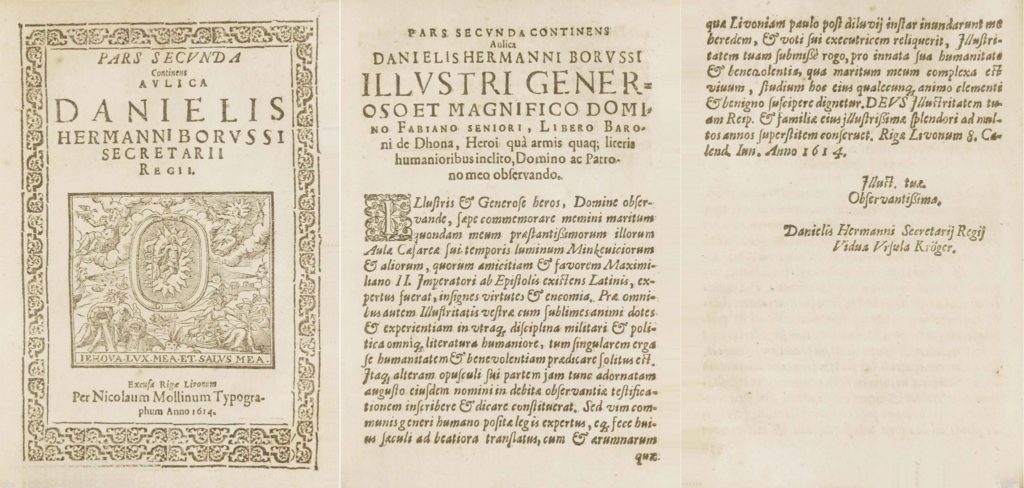

During this time, Europe saw a veritable boom of typography and one was opened in Rīga as well. Alongside printed books readers still perused manuscripts, plus the readers were involved in numerating the pages and coloring the first capital letters. Depending on the use, books came in different sizes, for example the so-called libro di banco were rather sizable books destined for use inside of universities and at home, laid on the table. Smaller books were destined for carrying around in the bag, they were used by traveling priests, pilgrims and traders. The smallest ones, libretto da mano or handbooks, were mostly classics and humanist literature for pocket carrying. In 1588 the Italian Ramelli (1531-1600) invented the bookwheel. It enabled readers to conveniently place several open books simultaneously for easy reading.

During the Renaissance, educated people's writings were often true examples of erudition rich in quotes, allusions and interpretations of what they've read. French philosopher and essayist Michel de Montaigne (1533–1592) probably didn't have a bookwheel in his study. He wrote the most important quotes on his living room walls. A bookwheel would have come in handy for Rīga's Basilius Plinius (c. 1540–1605), a poet and doctor who wrote an encomium to Rīga, praising the city in Latin as a haven of order, justice and peace.

(Image: punctum.lv. A bookwheel, 1588.)

The poem is rich in allusions to Greek and Roman mythology and literature as well as the Bible. It relfects Plinius' excellent knowledge of the city's fortifications and the texts of Renaissance historians. It started, as was the custom back then, with an address to the city and an allusion to classical literature, in this case Virgil.

What did women write and read back then?

As a rule of thumb, the higher her social status, the better educated the woman is. According to researcher Vija Stikāne, Anna, Duchess of Mecklenburg (1533–1602), who was the wife of Gotthard Ketler, Duke of Courland, wrote letters and managed business affairs. While Godela, widow of the Livonian fief Jürgen Von Ungern, held a written correspondence with Dorothea, the wife of the Prussian Duke. She wrote in Middle Low German instead of Latin. This old variety of German she used was called the language of women in Livonia, as it was more common in everyday life. After the death of her husband, Godela managed the education of her son. What's more – and this may be a unique example in the Baltic context – was her involvement in preserving her husband's literary heritage.

Rīgan Ursula Kröger, the wife of aforementioned humanist Daniel Hermann, was the reason why he stayed in Rīga. After her husband's death, she finished sorting his manuscripts and published them in Rīga in three volumes, and what's more she composed a dedicated introduction for each of them. By the way, in his youth Daniel Hermann wrote about 21 types of women, characterizing only one of them – the educated woman – as worthy. Hermann wrote that the conversation springing from her educated mind will enchant all of your senses. Apparently he found one such woman in Ursula Kröger.

And what about the Latvian-language readers?

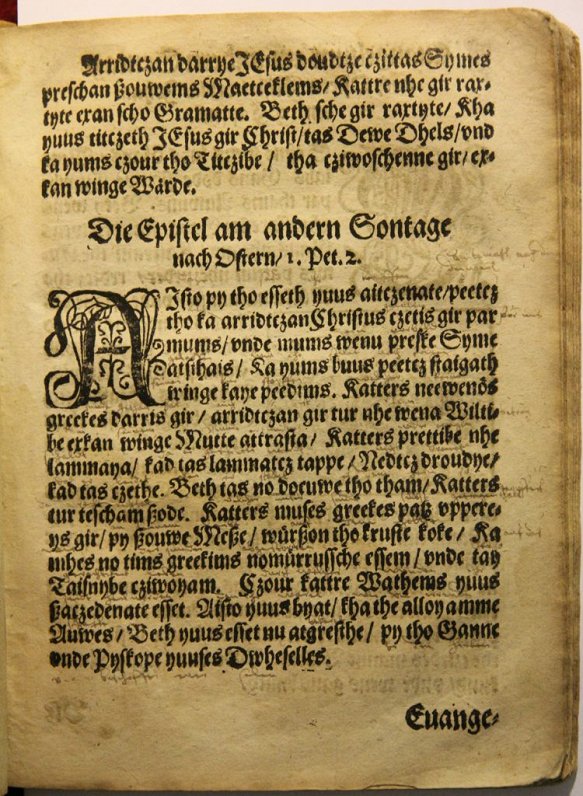

It is likely there were no printed works in Latvia prior to the Reformation. Maybe there were some manuscripts of prayers and songs. Martin Luther indirectly encouraged the appearance of Latvian-language books, asking clergymen to preach in the believers' everyday language. In mid-16th century Rīga, this was applied to the local non-Germans, or the Latvians. To preach, one needed to have Latvian-language texts. The oldest preserved books in Latvian were published in the late 16th century. Nevertheless the introductory pages thereof were in German, and therefore they must have been read by Germans – preachers, parish men, or, in the countryside, the landlords or overlords who had to read aloud and sing together with those who can't go to church. For example, a Latvian-language book has an inscription in the introduction: "vor das gemeine Haußgesinde vnd Pawren gelesen und erklehrt werden", which means "to be read and explained to the entire household and the peasants". Even though it was law that German and non-German children alike had to go to school, there wasn't much success in this regard among Latvians.

But in the latter half of the 16th century the entire Latvian territory fell to the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Jesuits traveled to the Baltics and aided the writing Catholic books in Latvian. In 1585, a Catholic Catechism was published in Latvian explaining the Catholic faith in the form of questions and replies.

(Photo: The New York Public Library. A page from the Latvian-language Gospels and Epistles in Latvian, published in 1615 in Rīga. German translations were hand-written above Latvian-language lines.)

The Catechism makes one think it was destined for Latvian readers. The title page is Latvian, and the book was published in an extraordinary print run of 1,002. Lastly, it was dedicated to "the untaught and young children". Church historian Staņislavs Kučinskis didn't even have doubt that the book reached the Latvians, but other researchers are more cautious over the matter.

Despite that Jesuits' books may have reached Latvian speakers, evidently it was too early to speak of a number of Latvian readers.

As the first Latvian books were religious, book as such became rooted in Latvian consciousness as part of church rituals. Some Latvians retained this belief until the late 18th century. Meanwhile Latvian texts often circulated among German preachers only as a tool required for a ritual, and nothing more. Tradition played a great role for decades and even centuries, as it was easier to repeat what one already knew. As such the first Latvian books, according to documents, were in use by German clergymen for another hundred years, even though there were more modern translations available in book fairs, having much better language and Latvian songbooks with new, rhythmical and euphonic songs by the masters of baroque.