Avots was first published in January 1987 and offered material that was sensational for the time, including banned literature, the works of the Latvian exiles, as well as exposes of the Soviet regime and other content that, in the era, was nothing short of pioneering.

The magazine's provocative nature started from its image, which sparked a number of scandals. It became a smash hit starting from the very get go, and within a year it was issued in 140,000 copies. To compare, the print run of the high-brow Rīgas Laiks monthly is about 5,000.

"We changed people's understanding about culture, and with it – of life," said Aivars Kļavis, former editor-in-chief.

Strangely enough, Avots and other similar magazines across former Soviet states were created within Moscow's corridors of power, with the support of the Communist Party. But starting from the very first issues these magazines turned against their financiers and their ideology. This was definitely promoted by the era's political events, as Mikhail Gorbachev had instated the perestroika across the Soviet Union, and in substance the entire union was writhing in agony at the time.

According to Kļavis, rumors on the magazine being made in the 20th story of the Press House started as early as six months before publishing. He had just started assembling a collective of young and talented people who still hadn't succumbed to the Soviet routine.

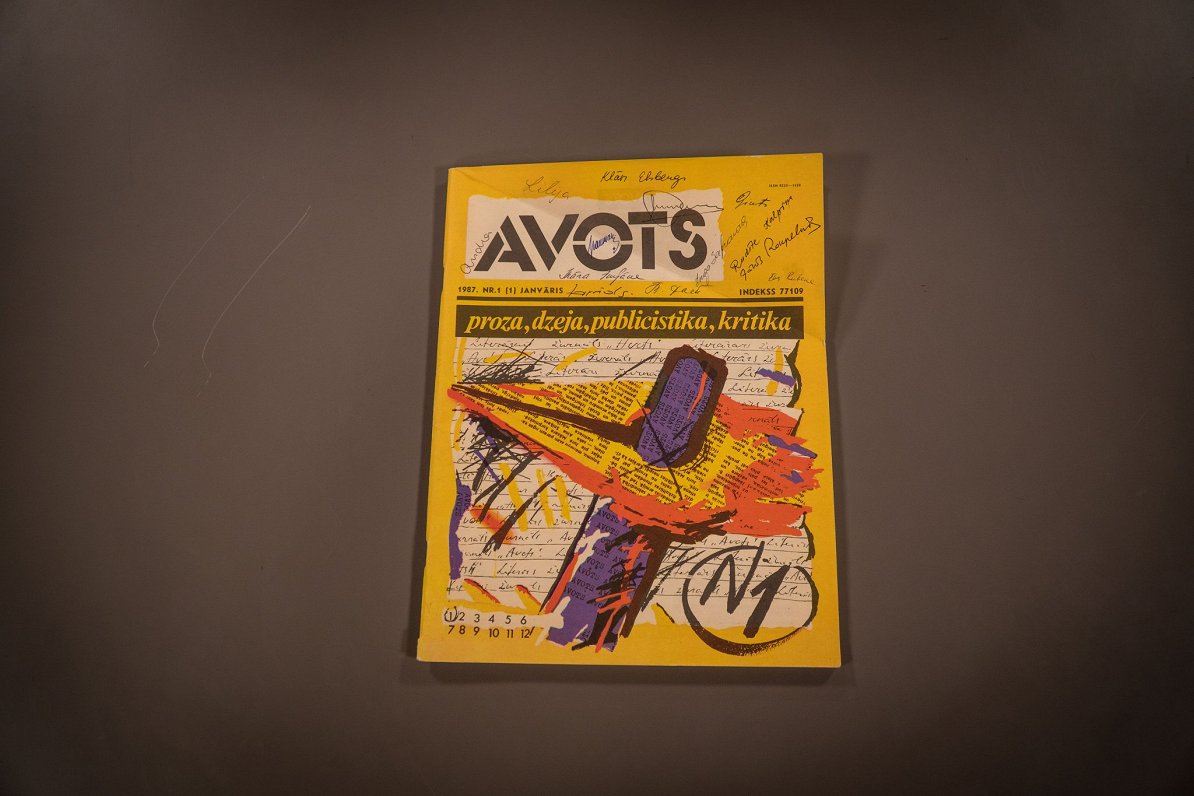

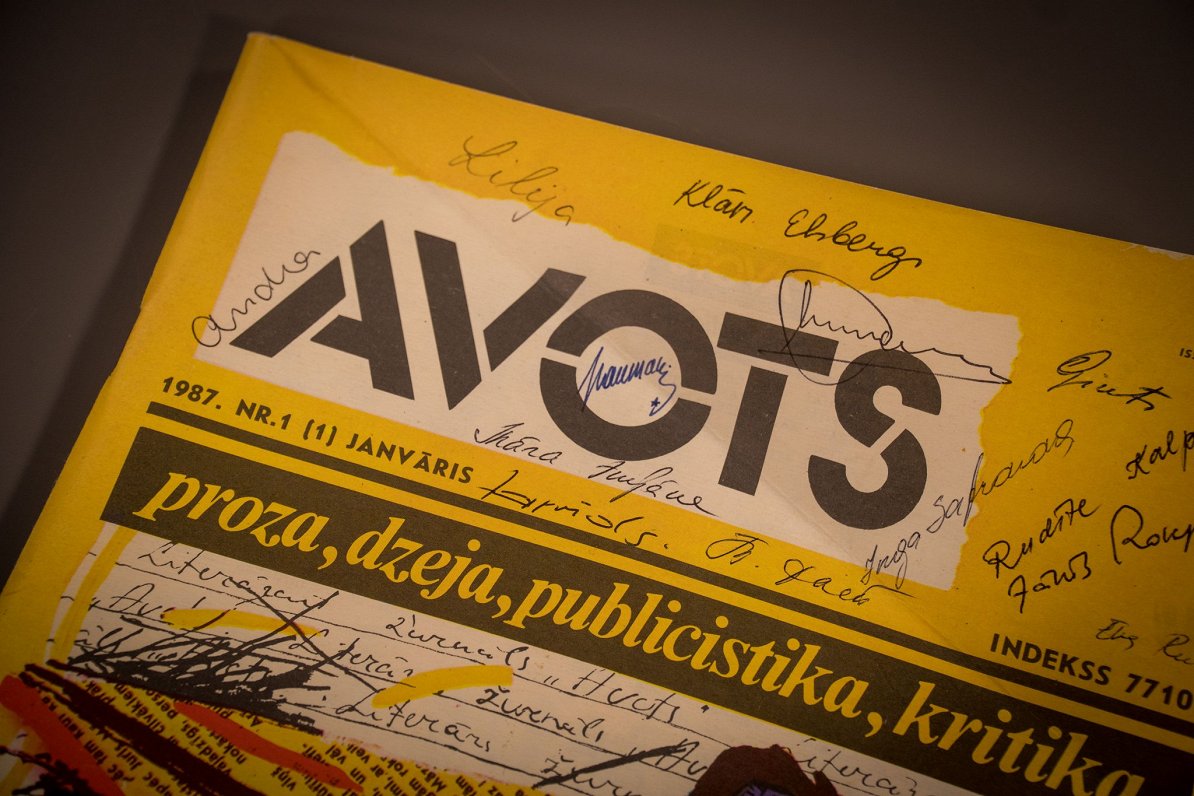

Among them were poet Klāvs Elsbergs, future cinema critic Normunds Naumanis, as well as writers Rudīte Kalpiņa, Eva Rubene and others – all are household names in Latvia even now. There were ten staff members in total. Avots had a Russian-language counterpart, the Rodnik magazine edited by Vladis Spāre. It became popular across the USSR.

"The cover is striking. We had big problems with it. It was a completely different style from the usual at that time," said Kļavis.

The January 1987 issue has a cover by artist and poet Andris Breže. It features a pen that looks a bit like a weapon – and even this is a result of last-minute changes as the original didn't get through censorship.

The biggest problems they had after publishing concerned Jānis Borgs' feature on dadaism. Aivars Kļavis was summoned to Moscow to visit the ideology secretary at the Central Committee.

"He screamed and cursed at me in Russian. It was incredibly humiliating. But they couldn't do anything about it as the magazine was there already," said Kļavis.

"Dadaism was something no-one in the Soviet Union talked or knew about. Dadaism, cubism, abstract art – it was something you spat and threw dung at. And all of a sudden there's a feature on it, an analytical and explanatory one. Oh my! And then he pointed a finger at the magazine, saying, 'Why dadaism? What right you had? Who gave you permission? Why didn't you cover the perdvizhniki?"

Kļavis says that afterwards he was subjected to bizarre punishment. "I was locked inside the Yunost' hotel of the Communist Youth Central Committee near the Lenin Peak. I was given three packages with some Siberian newspapers. I had three days to analyze these newspapers from the point of Soviet journalism and Marxism-Leninism and to give my evaluation about the content."

His encounters with the powers that be continued after the magazine published a piece on the State Security Committee (KGB).

"Reading the piece now, it doesn't have even one hundredth of what we know now. It was just that at the time the idea you had of a Cheka employee was that it's someone hot-hearted, pure and cool-headed. That was the Soviet Cheka employee – an ideal. And then we published a piece that they're actually murderers and that they've killed all those people and that it was actually a repressive institution," said Kļavis.

After Avots ran the piece, Kļavis remembers being subjected to what's known now as enhanced interrogation techniques inside the Cheka headquarters in Rīga, now a museum for commemorating the crimes of the regime. "There are many things my brain has shut out to protect the psyche," he said.

Among the greatest provocations by the magazine was a poster of Lenin's head inside a mousetrap. It sparked a huge scandal and once again Kļavis thought the magazine is done for.

As concerns literature, Avots' publication of Orwell's Animal Farm was by far the most scandalous thing they ran, but in addition many Latvian readers encountered Kafka, Cocteau, Nietzsche, Beckett, Salinger, Brodsky, Tarkovsky, Nabokov and others in the pages of Avots. The magazine also published Ojārs Vācietis' banned long poem Vadoņa augšāmcelšanās (The Leader's Resurrection) for the first time.

"I was young, impulsive and open, and I simply barged into the whole thing. On the one hand, we all had made a name for ourselves – more or less – in literature, and every new generation came with a freer spirit and a larger appetite for freedom, and so it was clear that this group of people would do something different. It was all directed towards renewing Latvian identity and self-consciousness," said Kalpiņa.

Sometimes they had to compromise to publish valuable content, Kalpiņa says. "I did the first interview in the magazine. It was with Jānis Vēveris, who was among those who were sentenced in the 1983 case that was fabricated against the dissidents Lidija Lasmane-Doroņina and Gunārs Astra. And if I'm not mistaken, in order for the interview to go through, Aivars Kļavis was forced to interview [formed KGB head] Staņislavs Zukulis. For a time we also made deals with spreads dedicated to Communist Youth next to completely disparate content," she said.

"Of course people who don't understand the time could ask, how come? You see, they did actually... Of course, that's true, but that's just the way you should interpret the era," Kalpiņa said.

Avots was in print for six years until 1992. It had accomplished its mission. Aivars Kļavis says that back then the staff didn't really understand their contribution, which has become clear only in time. "We have withstood the test of time," he said.

But the meaning the magazine had is reflected by the fact that many still store all its issues, and the content, too, has withstood the test of time.

* The Latvian Radio story was created in cooperation with the Baltic Centre for Media Excellence. Thanks to the National Library of Latvia.