“I never thought it would interest anyone until now!” Andris responds when I ask him what people do in the garages he rents out. “I've never really spoken about it. It's like keeping firewood in your shed – there's nothing to hide but also nothing interesting,” he continues.

I beg to differ! For someone without a garage or access to one, the “secret world” beyond the boom barrier and white sand-lime brick facade of the “standard” garage cooperative is intriguing.

Is it really just somewhere people park their cars? I was curious to find out how people use these spaces found in cities and towns throughout Latvia and what their future might be with the shift away from car-centric planning.

The cooperatives sprang up in the second half of the 20th century as somewhere for residents of the new block buildings to keep and fix their cars. In 2015, they became the topic of Latvia's exhibition at the Venice Biennale and, a year later, artist and filmmaker Katrīna Neiburga produced a documentary, revealing the space as something of a playground for grown men. Does that still hold true?

To find out, I spoke to Andris (he prefers not to give his surname), well-versed in the real estate industry and the owner of several garages in Cēsis, plus Kārlis Jaunromāns, an architect, Pēteris Čeliševs, chairman of the board of the Manēža garage cooperative in Riga, Arnis Gross, a garage owner, and Madara Brūvere, a car enthusiast.

Madara tells me that the coops are still very much a 'man's world'.

“People have always had sofas and radios in their garages but during the pandemic they became a place to hang out and party. It's where men go to let off steam away from their homes and wives,” she says. Her family has had a garage in Jugla, on the northern outskirts of Rīga, since the 1960s, and she started to spend time there with her dad at the age of three while her mum was at home with her baby brother.

“Dad would give me tasks like pumping the tires. I still remember, it takes 200 times to pump a Zhigulis tire.”

Since then, Madara can't imagine life without a car, and even admits she likes the smell of cars and garages.

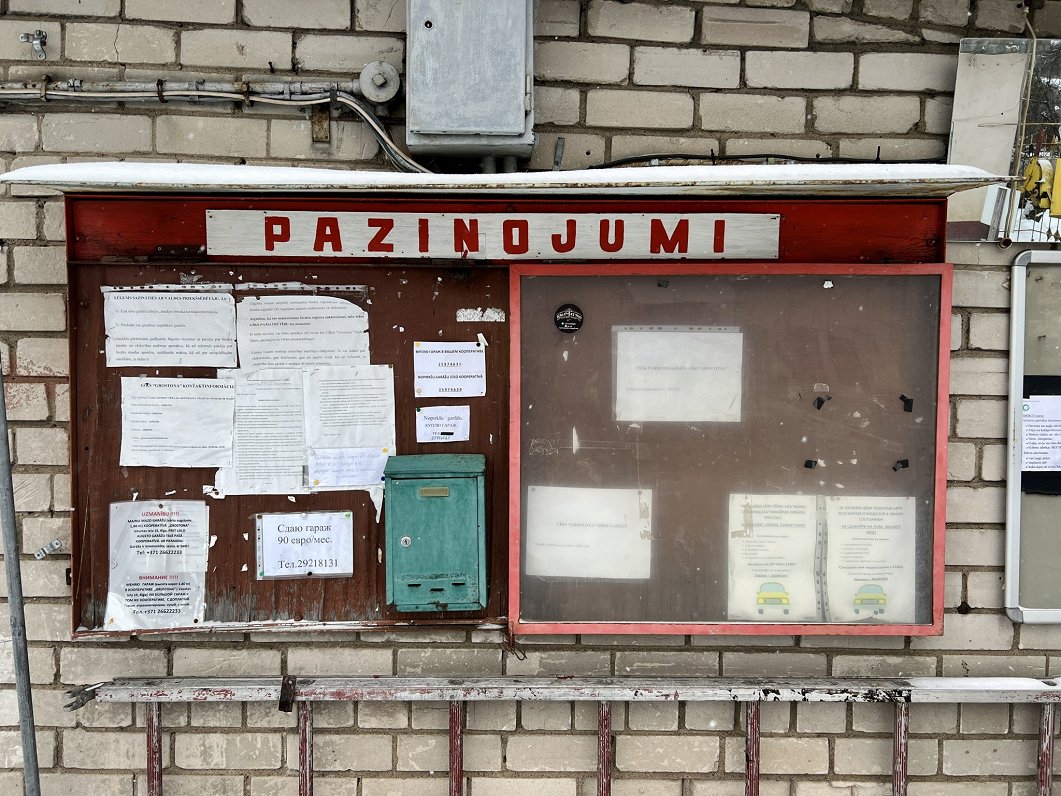

Arnis Gross takes me on a tour of a cooperative on the banks of the river Daugava in Rīga. I soon learn that the midst of winter isn't the best time to visit. He paints a picture of the summer months with garage doors flung wide open, people picnicking and playing novuss [a Latvian billiards-crossed-with-checkers game] between the rows of garages and on the grassy patches by the river. In temperatures far below zero, it's swamped in silence with very little going on. A bit of smoke emerges from the chimney of one of the heated garages, suggesting some action inside.

For Arnis, the garage is a storage space and “man shed”. Having spent a fair bit of time at the coop, he's made several observations, like the changing demographics. The garages are now attracting younger, more affluent users, who keep things like motorbikes and SUP boards there. At the same time, for others they still serve as cellars for pickles, veg and preserves as well, since most garages have a pit, designed for fixing cars from underneath, which are actually a multifunctional space. Some people run their businesses from a garage. At this particular coop, you can get your car fixed at an auto repair shop, but other business owners like contractors use their garages to store their tools and equipment. Arnis says that the price of garages has shot up since the pandemic, proving their popularity.

Pēteris Čeliševs confirms the trend: “Five years ago, you could get a garage for EUR 1,000, but now nothing starts from less than EUR 5,000 to EUR 7,000”.

At the time of writing, one garage on Riga's Vesetas iela was being advertised for EUR 9,500 and another for EUR 14,900. Many rent their garages, paying a fixed amount per month along with the coop fee to cover costs like security and maintenance.

“Demand is there! We may not have a waiting list but I get calls every day asking about availability. It's the location. Lots of people in the area don't have access to garages. Parking on Vesetas iela is now paid-for,” says Pēteris. “On the street, car lights and bikes get stolen. People want security. The car parks are overrun,” he explains. At his coop, 95% of the garage users keep their cars there, however, “You can't really know what people store there. You can't just ask 'What will you be keeping there?' at the time of sale or renting it out,” he adds.

Meanwhile Andris first realized the potential of garages when he bought a house that came with a set of four. Since then, he's purchased several at coops throughout Cēsis and rents them out, comparing it to other types of real estate investment: “I don't see much profitability but it does stop inflation. When you have any spare cash, you start to wonder where to invest it. While one buys expensive cars, another opts for real estate.”

Even though “prices are sky high at the moment”, demand is high in Cēsis too. “There are no free garages. The situation is better in Valmiera, perhaps because it's easier to find work there, income levels are higher and property cheaper,” Andris comments. He believes that many people are unaware of the value of garages today.

“I'm more than sure that many garages aren't in use. Perhaps a grandfather once used it and passed away, and his children don't care for it, don't realize that it might interest someone, or they don't even know about it because the paperwork isn't complete. It could be that they only own a share of the coop – a so-called “paja” – which is just a piece of paper, and nobody knows any more than that. You do see overgrown doors. If all that were sorted out, there'd be enough garages.”

People are even willing to travel to the garages.

“You'd think a garage is only interesting to people who live nearby – that you wouldn't walk a kilometer to get to your car. However, the reality is different. I know a woman who found that the bus stops directly outside her house as well as the garage cooperative,” says Andris. “It's rare for women to rent a garage. She's a car enthusiast but only uses her car in summer, keeping it locked away in winter,” he adds.

Considering his knowledge of the real estate market, Andris thinks that garages are a thing of the past in the sense that it would be too expensive to build something like that today. “You can't build anything new with the money you cash in each month. To do it as a business project would be amazing but tough,” he says.

He believes that the existing garages are here to stay. “Nothing should change. People still have apartments and the same needs. Plus, the number of cars is increasing.”

If anything were to change in the way we use garages, their future seems bright anyway, according to Kārlis Jaunromāns, one of the founders of the Tandeems design and architecture competition platform, which is hosting a challenge on the future of the garage, aiming to identify ways to repurpose, upgrade or reimagine a cooperative in Cēsis.

“They have so much potential!” he muses. “You can imagine a garage, a workshop, even a studio apartment by adding another level,” he adds, sharing that their partner organization in Estonia runs creative workshops at a garage cooperative in Tallinn.

Interestingly, some garages at the Rītabuļļi coop in Riga's Daugavgrīva neighborhood have already been transformed into living space by adding another level.

“The garage is a modular building, which means you can apply a standard solution. Since they have flat roofs, the roof space too is usable. Also, considering that the cooperatives are gated, they make great spaces for experiments, a certain freestyle and creative approach – an excellent location for experimenting with recycled construction materials with no historical value, compared to, say, central Riga where the building regulations can be quite strict,” Kārlis continues.

Besides, this type of garage is not unique to Latvia. “Looking into the building typology, we see that they're identical in all former Soviet countries. By developing interesting proposals for one place, they can be used in many,” says Kārlis. “It will always be more sustainable to find a use for something existing than to reduce it to a powder for making something new,” he insists.

However, the cooperatives are an unusual case both from a legal point of view regarding ownership, and demographics, according to Kārlis. “From what I've found so far, the only thing clear to me is that it's a complex ecosystem – how it took shape administratively and sociologically. To imagine that there's a one-size-fits-all solution? The margin for error is very high.”

He proposes prototyping as the best approach to such challenging places. “Visioning and generating ideas are the only way to reach consensus. People need something to look at to spark a discussion. Take part of a place – even just six garages – research it and acquire some qualitative data,” he suggests. “You have to speculate and experiment with functionality. It's impossible to just know. It calls for testing,” he adds.