Latvian Radio retraced the footsteps of this fascinating historical event in a story that appeared on LSM Friday.

Legendary warriors

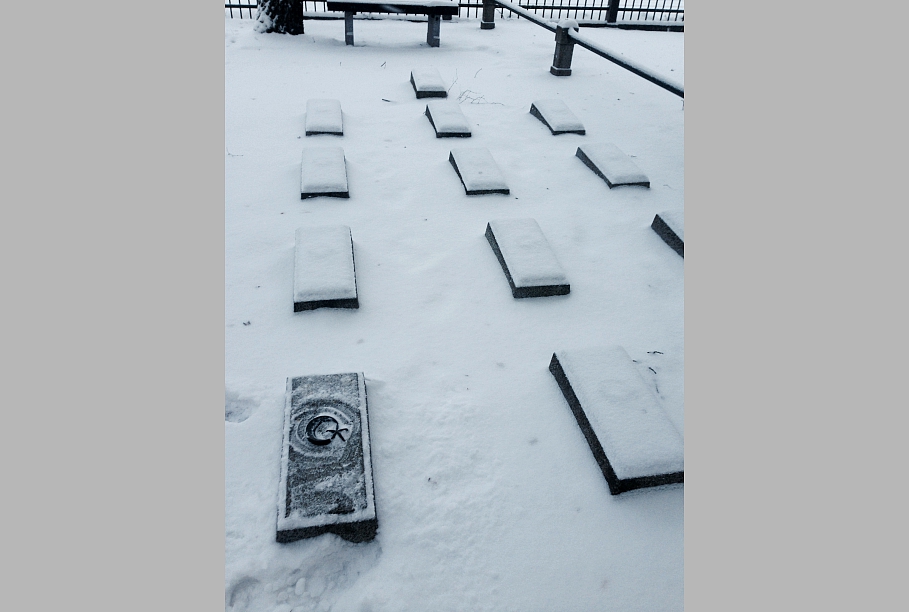

Latvian Radio was guided by Tālis Pumpuriņš, a specialist at the Cēsis History and Art Museum. The visit took place on a winter day. The graves of the Turkish soldiers were covered with snow, making them all but indistinguishable from the others. The graves are arranged in several lines, surrounded by trees. A monument is towering in the middle.

Removing snow from one of the graves, you can uncover a crescent and a star - the symbols of the Ottoman Empire, and now the state of Turkey.

"Yes, there's a crescent and a star on every grave. The names and surnames are known, but they're not written on the graves. You can see the monument that the municipality established in 1878," said Pumpuriņš.

Even though the wide-reaching cemetery is on a hill and seems more like a memorial, not all the locals have heard of it. [Editor's note: Our editor-in-chief Mike Collier, a Cēsis local, made a video about the cemetery two years ago.]

To learn how the Turks ended up in Cēsis, Latvian Radio went to the War Museum to talk with historian Juris Ciganovs. The War Museum has but a few testimonials about Latvian soldiers of that time - only a single memorial medal plus a map of the Russian-Turkish war.

Ciganovs said that the war of 1877 was important as due to mass conscription the first officers gained vital experience in the war.

"One of the best-known participants in the war was Andrejs Pumpurs, the author of [Latvian first] epic Lāčplēsis. He sent descriptions from the war to our newspapers," said Ciganovs.

"However it is not known how many Latvians fought in the war. Such information is perhaps to be found in Russian archives," speculated the historian.

Polite and respected

Perhaps the archives would also explain how the Turkish prisoners got to Cēsis. At the moment it's only clear that when Russia beat the Ottoman army by the Bulgarian city of Plevna in September 1877, the Russian army decided to do something unprecedented with the numerous POWs.

"It was a new thing, when after the battle of Plevna Russians took a huge number of Turks captive and they were sent to different regions of Russia by quotas. A few hundred were taken to Cēsis where they spent the years of war," said Ciganovs.

The Turkish prisoners didn't influence the life in Latvia or Cēsis much. Accordingly, there has been little interest in them, and there is little testimony to their presence so far away from home. There are only legends, which Tālis Pumpuriņš related to Latvian Radio.

"First they lived in Cēsis under supervision, but afterwards, as they were so far away from their motherland, their regime became freer - they could traverse the city, go to the pub, the sauna. After a while some went back to their homes, while others struck root in Cēsis," said Pumpuriņš.

While one Kārlis Dzirkalis documented the life of the Turks in Cēsis, in a piece published on sargs.lv:

"The Turkish prisoners were dressed in grey-brown short-coats, with light footwear. On their head they wore red felt fezzes with a black plume and a crescent in front. Some had a white or motley towel tied around the fez, while others had motley and red kerchiefs in place of fezzes. The prisoners were of different ages - young and old, with and without a beard," Dzirkalis, who was important to promote awareness of the Turkish prisoners in Latvia, wrote.

"They were of a dark-skinned and lithe complexion. They were very polite towards locals and so became generally liked by everyone," wrote Dzirkalis.

"They mostly moved in groups, rarely alone. Women and children were a little afraid of them though. The prisoners were very peaceful and honest. Russian soldiers got along with them well too. When meeting on the street they screamed something in their own language, which no one understood. It was the ordinary 'salam alaikum' greeting."

Thus wrote Dzirkalis, who was the author of the idea for the Turkish cemetery monument. He is known as one of the scout movement organizers and participated in the 1919 battles by Cēsis.

Only graves left behind

"The Turks were forced to leave the city when World War I began. Cēsis was pronounced a frontal city and Turks were once again on the opposing side," said Pumpuriņš, who prepared an overview of the cemetery's history for Latvian Radio.

The only testimony to Turkish prisoners in Cēsis is the cemetery, where those who died the first winter were buried. Presumably due to the climate the Turks fell ill with several respiratory diseases and later typhoid. Pumpuriņš said the cemetery was placed near the barracks where the prisoners resided. Back then the place, now with houses nearby, was much more solitary. "There are 25 Russian-Turkish prisoners of war. The 26th was a Kyrgyz who dug trenches in WWI and was laid to rest here as a Muslim, alongside his brothers in faith," said Pumpuriņš.

The Turkish cemetery in Cēsis

Winter/spring 1878 - 19 fall ill and die from typhoid

March 1878 - Adolf Wiebeck (1837-1878), the city doctor at Cēsis, who treated the POWs sick with typhoid, falls ill himself and dies.

Summer 1878 - the municipality erects a 1 meter high granite stone

1879 - most of the prisoners return home, while some settle down in Cēsis

World War I - as Russia and Turkey are at war, the Turks are sent to interior Russia

1936 - Kārlis Dzirkalis (1902-1997), inspector at the Cēsis resort committee, architect and social worker turns to local authorities and Turkish diplomats in Latvia with a request to landscape the Turkish cemetery.

September 1937 - opening of the landscaped cemetery

2004/2005 - reconstruction of the cemetery. The plaques and flag masts are renewed, as well as the lost crescent and star symbols.

2008 - the cemetery is named a Europe's extraordinary cultural heritage monument.

He also said that Adolf Wiebeck, who treated the sick prisoners of war, has been unjustifiably forgotten. He caught typhoid from the prisoners and also died. He was buried in the German cemetery in Cēsis.

Turks in the Turki parish

However Turkish fates in Latvia don't stop in Cēsis. There'a a Turki parish near Līvāni, in eastern Latvia. More than 30 years the chairman of the parish is Aivars Smeceris, who was prompted to look for the etymology of the name due to the strange name, which means simply 'Turks' in Latvian.

Smeceris was very eager to talk. He told Latvian Radio that he found information in the archives of Russia and Belarus. It's written there that more than 700 Turkish soldiers, who were taken prisoner by Shipka and Bazargic (now Dobrich) in Bulgaria and were kept, in early 1878, in Kreutzburg, named Jēkabpils now.

"There is information corroborated by a Russian State War History Archive certificate as well as one from the Belarusian National History Archive that there's an order for the Vitebsk governor from the Vitebsk war district head for creating an infirmary in Kreutzburg or Jēkabils, for supplying necessary medical personnel and different wares in order to house 727 Turkish prisoners of war in February 1878 and March," said Smeceris.

Documents certify that 236 of them were given bed-clothes, footwear, and were settled in barracks-style buildings in Jēkabpils.

Smeceris also told about a telegram that asks to transfer the Turkish prisoners as there were increasing numbers of fires for which the prisoners of war were partially responsible.

It is not clear whether the prisoners were afterwards transferred to the Turki parish which then would have been named after this historical event, but admittedly unverifiable tales of the locals are the only testimony to that, as no graves or church records reveal their further fate.

A refugee parallel?

The Turkish prisoners were, much like refugees of the day, sent to regions of Russia by quotas.

Even though the historian Ciganovs was quick to say that the two are completely different, Latvian Radio's Dace Krejere muses - isn't it strange how today we're so afraid of the far-away, alien people, while in old legends about other far-away aliens we impart an exotic veil on them and are even proud that they have been here?