The index measures perceived levels pf public sector corruption in 175 countries and territories.

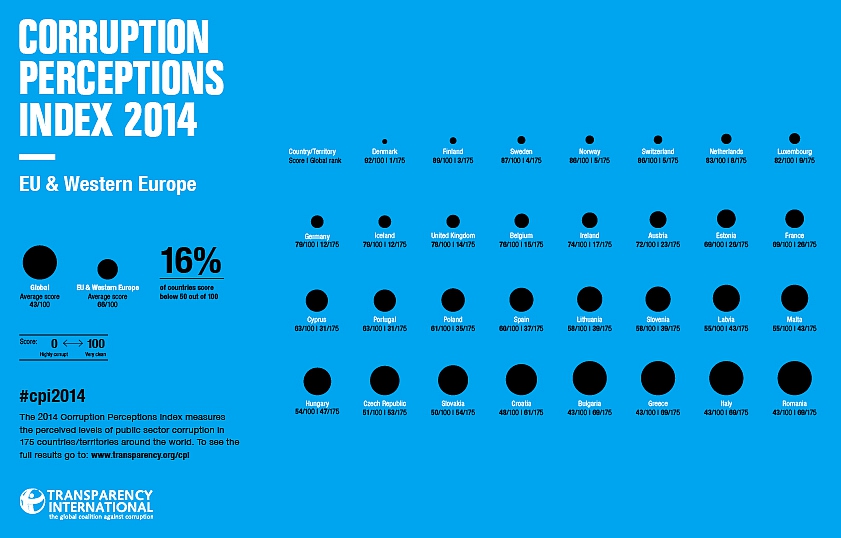

Latvia ranked in 43rd place overall, behind Baltic neighbors Estonia (29th place) and Lithuania (39th place).

Nevertheless, the ranking is six places higher than last year's index in which Latvia was in 49th spot.

Significantly, Latvia now ranks considerably higher than a number of its European Union peers including Hungary (47th), the Czech Republic (53rd), Slovakia (54th), and both Greece and Italy (joint 69th).

Launched in 1995 the CPI has become an influential barometer of how corrupt societies view themselves to be.

In 2000 Latvia was reckoned to be the 57th most corrupt country out of 90 surveyed.

By the time of EU accession in 2004 it was still ranked 57th, but this time out of 146 countries.

Since then the rating has generally improved, moving to 52nd spot out of 180 countries by 2008 but dipping to 61st spot out of 183 countries in 2011 in the wake of a severe economic crisis before bouncing back to 54th out of 174 countries in 2012 and 49th from 177 last year.

In the 2014 index, Denmark secured first place with Somalia and North Korea bringing up the rear.

"Corruption is a problem for all economies, requiring leading financial centers in the EU and US to act together with fast-growing economies to stop the corrupt from getting away with it," Transparency International said in a statement.

“Economic growth is undermined and efforts to stop corruption fade when leaders and high level officials abuse power to appropriate public funds for personal gain,” said José Ugaz, the chair of Transparency International.

“Corrupt officials smuggle ill-gotten assets into safe havens through offshore companies with absolute impunity,” Ugaz added.

“Countries at the bottom need to adopt radical anti-corruption measures in favour of their people. Countries at the top of the index should make sure they don’t export corrupt practices to underdeveloped countries.”

The Corruption Perceptions Index is based on expert opinions of public sector corruption. Countries’ scores can be helped by open government where the public can hold leaders to account, while a poor score is a sign of prevalent bribery, lack of punishment for corruption and public institutions that don’t respond to citizens’ needs.

Transparency International called on countries at the top of the index where public sector corruption is limited to stop encouraging it elsewhere by doing more to prevent money laundering and to stop secret companies from masking corruption.

While top performer Denmark has strong rule of law, support for civil society and clear rules governing the behavior of those in public positions, it also set an example this November, announcing plans to create a public register including beneficial ownership information for all companies incorporated in Denmark.

The measure, similar to those announced by Ukraine and the UK, will make it harder for the corrupt to hide behind companies registered in another person’s name.

The anti-corruption group is currently running a campaign called Unmask the Corrupt, urging European Union, United States and G20 countries to follow Denmark’s lead and create public registers that would make clear who really controls, or is the beneficial owner, of every company.