Formerly a dominant force in Latvia's politics, and, as the country became independent, its cultural and economic life, the Baltic Germans disappeared in a matter of months, thanks to occupying forces and local nationalist currents.

In 1939, there were 62,000 Baltic Germans living in Latvia. They were the third-largest minority following Russians and Jews. About 50,000 left Latvia in the fall of 1939, and a further 11,000 left in spring 1941.

Hitler had ceded the Baltics to Stalin, and made haste to call his "race" home before the Soviet occupation came.

Wealthy, educated and socially active

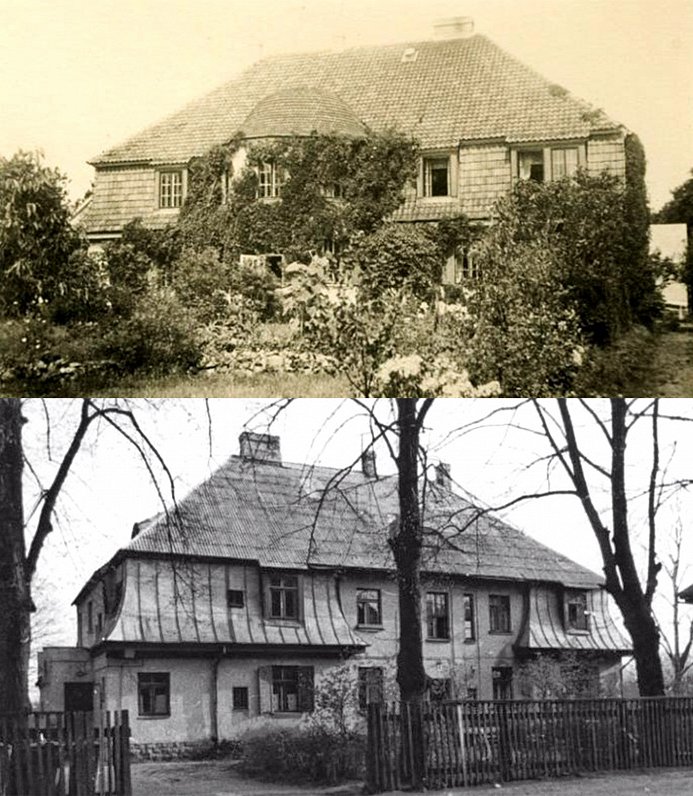

The architect Bernhard Bielenstein was a country boy. He took care to create a sylvan idyll in his family garden at Rīga's Mežaparks neighborhood. Bielenstein inherited his love of country from his father, the Dobele pastor August Bielenstein, a famous plant breeder, researcher of the Latvian language and ethnographic tradition, as well as head of the Latvian Literary Society and honorary member of the Rīga Latvian Society. The Bielensteins were German. In 1939, already a graying man, Bernhard and his wife left their nest which they had looked after for decades. Almost all the Germans living in Mežaparks, about 600 in total, left at the same time as him for fear of the Russian occupation.

Mežaparks, which is still the richest neighborhood of Rīga, was a citadel of Baltic Germans. Until the First World War, it was mostly built up and inhabited by Germans. During the inter-war period, they were also the elite of the society. They were wealthy, educated and socially active.

Despite making up just 3% of the population, Baltic Germans owned 17% of the factories, trade companies with a total 16% share of the country's market turnover, and almost 30% of Rīga's large-scale apartments. There was a Baltic German party in the Saeima; they had their own unions, corporations, schools and even an university -- the Herder Institut in Riga.

As concerns identity, Baltic Germans were not that eager to see themselves as belonging to Germany.

Instead, they lived with an idyllic conviction (which Latvians weren't keen on adopting) that together with the local people they share a common Baltic identity. Researchers think that Baltic German blood was about one-fifth Latvian and Estonian.

Tension between Latvians and Baltic Germans

Since the early days of Latvian statehood, there was tension and a sense of unsettled accounts between Baltic Germans and Latvians. The Baltic Germans felt humiliated due to the power they had lost and the nationalization of their former manors. For a part of them, the chauvinism of being a "kingly folk" hadn't died down yet. Meanwhile, Latvian self-confidence grew and we were keen on weeding out the remaining symbols of German dominance.

The first of the highest steeples in the Old Rīga skyline to be confiscated from German and Latvian Lutheran parishes was the St Jacob's Cathedral, which per a 1922 Latvian treaty with the Vatican was granted to Catholics as a reward for the integration of Catholic Latgale into Latvia.

In 1931 the Latvian parliament took away the Rīga Cathedral from the Germans too, for the needs of the bishop of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Latvia. The Latvian bishop Kārlis Irbe actually resigned in protest, but that was not enough to put a stop to rampant nationalism and populism. Only the St. Peter's Church remained in the hands of Baltic Germans.

The authoritarian (or dictatorial) regime of Kārlis Ulmanis took to burning bridges with an even greater sense of urgency. German homes in Old Rīga were demolished; the entrance to the German war cemetery was blocked by a monument to former president Jānis Čakste, the autonomy of German schools was revoked; the role of the German language in public life was curbed; and German work in law practice was limited.

Particularly painful was the disbandment of the two German-majority craft guilds (the Great Guild and the Small Guild). Even though it was long since they had wielded any real influence, Ulmanis nationalized the centuries-old properties of the guilds.

Since the early days of Latvian statehood, there was tension and a sense of unsettled accounts between Baltic Germans and Latvians. Just one of the three highest steeples in the Rīga skyline was left in German control.

The wave of authoritarianism sweeping through Europe polarized the Latvian people.

The nationalist Ulmanis stirred up the Latvians, while Hitler put fog over the Baltic German eyes.

Young Germans in Rīga believed that they would colonize Russia together with Hitler. In 1933 the formerly loyalist Rigasche Rundschau newspaper was taken over by local Nazis, and its long-time editor Paul Schiemann was forced into exile.

Repatriating the Baltic Germans in Latvia and Estonia

In 1939, the twilight of the Latvian state was closing in, like a deadly avalanche. On August 23 the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was concluded; war broke out on September 1; the military base agreement, forced upon Latvia by the USSR followed on October 5.

On that same day, German envoys in Rīga and Tallinn received a note from the Reich tasking them to inform the Latvian and Estonian governments about the repatriation of Baltic Germans. This operation had been planned in great haste and secrecy by Hitler. The Baltic states only learned after the agreement was struck between Germany and the Soviet Union.

A total of 80,000 Latvian and Estonian citizens had their fate decided by the totalitarian powers, unknown to them.

Germany concluded an agreement about the repatriation of Germans on October 30, and it started on October 31 at 9 a.m. Repatriation points were set up, including one at the House of the Blackheads, a long-time German stronghold in Old Rīga. People formed queues to leave their native land: "With this, I willfully revoke my own and my children's Latvian citizenship for all time, as well as our rights to return and settle in Latvia."

They left Rīga, Ventspils and Liepāja on ships. The streets were full with carriages hauling furniture. Their real estate was taken over by a public company set up for the task. Baltic German companies were closed. The first ship left Latvia on November 7, and the last left the Baltic shores on December 16.

There were some who sang "Deutschland über alles" as they sailed away. Others preferred "Dievs, svētī Latviju!".

Hitler's secretly-planned repatriation took place at such haste it would be more aptly termed an evacuation.

The Baltic Germans did not, however, go to Germany but occupied north Poland instead. They were given a chance to save themselves but were recognized as German citizens only after "loyalty" and "racial hygiene" tests by the Germans. Baltic Germans did not have any ties whatsoever with the land they were shipped to.

Bernhard Bielenstein wrote: "We didn't arrive to our fatherland, our homeland." Nevertheless, even the people who really loved Latvia went away as they feared the Bolsheviks and did not want to lose contact with their fellow German speakers.

Support for Baltic German repatriation

The Ulmanis government encouraged this, for reasons that had to do with both domestic and foreign policy. Ulmanis wanted to please Hitler as he naively hoped for German support in face of an impending Soviet invasion. Latvia even shouldered the costs that Germany paid to the repatriates in compensation for the property they left behind.

While domestically speaking, Ulmanis used the repatriation as an opportunity to cultivate the myth of building a "new, Latvian Latvia".

Those who did not want to leave (there were many) were warned by the authorities that they would be considered as revoking their German ethnicity and would be considered "citizens of conjecture", who sought to gain from remaining here.

Those who did not want to leave loved their country, hated Hitler, were too old or too poor, or had relatives here.

This mass repatriation came as a shock to everyone. Rumors arose over an impending Soviet attack. But several thousand Latvians were among those who left. "Whatever their reasons, if someone wants to leave, let them, but they should know that leaving is possible only in the German way -- once you go, there's no turning back!" said Kārlis Ulmanis.

A considerably emptier Latvia

About 50,000 people had left Latvia in a matter of weeks. They were mostly the elites. It sparked an economic crisis. Demand decreased rapidly as the greater spenders had left. Real estate prices plunged as thousands of apartments had been left, some Rīga streets were abandoned entirely. The GDP was riven down by the closure of hundreds of companies. There was a labor shortage as well. A gaping hole had been torn in the Latvian nation.

It would only grow bigger, as Stalin allowed Hitler to take a further 11,000 Baltic Germans home -- they had not left yet. These were followed by Soviet deportations, the Nazi holocaust, refugees leaving for the West, and even more deportations. Latvia's population decreased by a third, and the economic and cultural elite was almost entirely destroyed.

But the houses remained standing. That's what Bernhard Bielenstein called his memoir: But the Houses Remained.

Villas in Mežaparks became communal apartments, where four to eight families were settled in places where just one or two had formerly lived. The Bielensteins' house experienced a similar fate. It's a sorry sight now, and is likely to remain so for the foreseeable future.

One house across two eras. The former sylvan scene at Bielensteins' home was replaced by a communal apartment.

Despite the resentment from the times past, Baltic Germans were a flourishing flower of our nation. Just like any other minority here and now.