Recently, former Labvakar journalists Jānis Šikpēvics and Ojārs Rubenis told Latvian Radio their stories about the time at the studio as part of a series of publications leading to the 30-year anniversary of the May 4, 1990 Supreme Council vote to reinstate Latvian independence.

The way it began

"I was young and crazy, I was 24 and started working at LTV. Strangely enough, at the department of propaganda, and in order not to lose the vacancy they hired me there," said Ojārs Rubenis. He started working at the television in 1979 and was often tasked to write stories for "profession days", which were dedicated to food technologists, builders, industry workers and so forth.

Later, in the latter half of the 80s, Rubenis started working at Stopkadrs (Freeze Frame) and Risinājumu meklējot (Searching for a Solution). These broadcasts concerned socially important problems but without harsh criticism directed towards the Soviets. "I was interested in construction, and the industry had huge problems. All the panel buildings and the way construction took place. I saw the strangeness but perhaps on a personal level. At the time, the four of us – me, my wife, and two children – were living in a single 16m2 room at a communal apartment. It had no warm water, bath or shower," said Rubenis.

"At the time I thought that something somewhere isn't really coming together in life. We did not doubt communism or socialism at first. We simply asked to explain why someone has to get by with 16 square meters if new housing is built nearby, which is provided not to the base population but immigrants. Why isn't the system just and what can we do about it? It developed into a situation where the people in charge couldn't refuse television interviews as TV was a big force back then," Rubenis said.

Western music, inspiration from Moscow

In 1987 the Moscow Central Television started broadcasting Vzglyad (The View), an informative show created by a Communist Party decision. The show featured interviews – including critical interviews – with politicians and played some Western music. After it was set up, it was decided that Latvia too would acquire a similar program.

"I don't know who greenlighted [the broadcast], as no one from any institution talked to me or Edvīns [Inkēns, the third host at the show]. And then we were very happy we can make something new. There wasn't anything like it on our television, and we took Vzglyad as the basis for the program," said Rubenis.

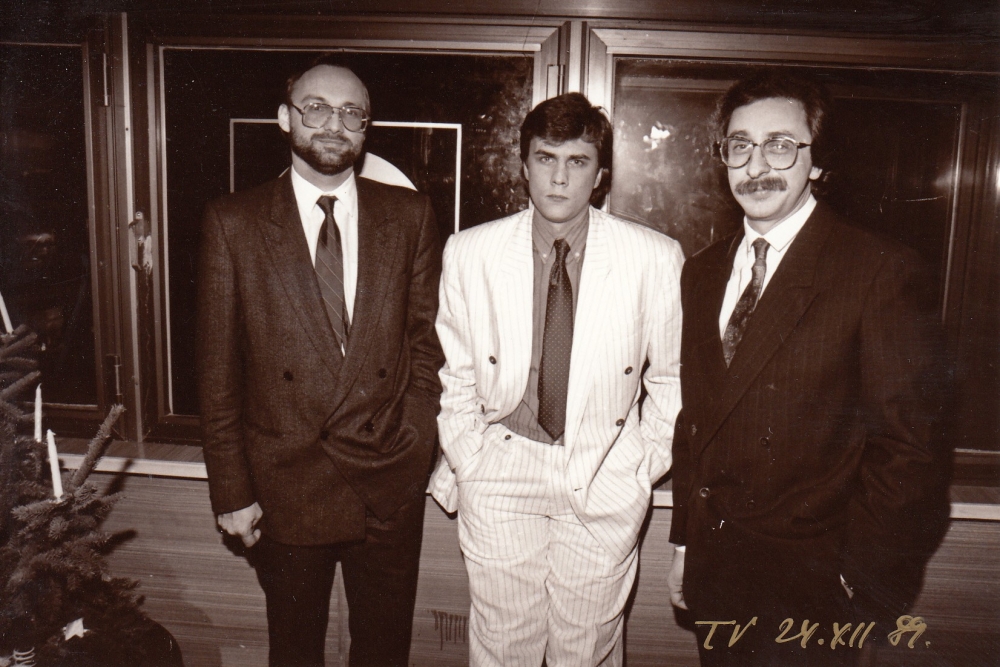

Inkēns and Rubenis were soon joined by Jānis Šipkēvics, initially in charge of music programming. "Behind the Iron Curtain, rock music and the likes were every bit as illegal as talk of independence or leaving the USSR. I wanted to opt-out from conservative music tastes and promote freedom as concerns different genres of music. With my youth, energy and perhaps cockiness I got in with these two guys who were also quite cocky," said Šipkēvics.

Šipkēvics had started working at LTV in the early 1980s as part of its Music desk. He started work at pushing formerly illegal music videos, broadcasting them in the Planētas balss (The Global Voice) program.

"As a treat, they usually showed Boney M's Eruoption, maybe ABBA or someone else from the West. I offered a beautiful video with Julio Iglesias and Diana Ross where everyone's at a pool with a glass of champagne. At the same time there was a big anti-alcohol campaign in the USSR, and you couldn't show a glass or a bottle on TV. And I had to paste up all the glasses in the music video. On the one hand, it's an inexcusable intervention of another artist's work, that you had to mess with it because there was a stupid prohibition. On the other hand, it was clear that otherwise the music video would have been thrown away," said Šipkēvics.

For every broadcast, they had to come up with an explanation or legend as to why this English singer should be shown on television and what's there to gain for the people at work building communism. A special committee reviewed the videos prior to broadcast.

"All the broadcasts were reviewed before airing. Three or four people did this. There was a single TV set there, and I knew which spot would attract their attention. And at that point I sent in the director's assistant with cookies and coffee. She entered, turned her back to the TV set and her face to the committee. It was timed so that they miss the suspect 20 seconds. I had to spend time on nonsense such as this," Šipkēvics said.

Censorship, and the circumvention thereof

Early on, Labvakar didn't face much trouble as for the first three months the program only discussed domestic problems. However as public interest was growing people entrusted more and more letters to the journalists, relating their troubles caused by the system. And the journalists found ways of relating matters of public concerns to the audience.

"See, you tell people about someone who hoisted the red-white-red flag and was fined for it. And we don't use the story to say that it's a bad thing to do but instead say that it has happened and that someone has made a choice. What the viewers get is the idea that you are allowed to discuss this. And we can't reproach people for that, as we live inside such a system. But many had the feeling that something's amiss. I was born after the war and it took me a lot of time to realize something's amiss," said Rubenis.

On March 25 local Soviet authorities, for the first time, allowed a commemorative event to be held for the anniversary of the 1949 deportations. A protest was held by the Freedom Monument, with the Labvakar team filming the event. Journalists were put behind bars, but the story was still broadcast on TV.

Rubenis ventured to suggest that many of the banned stories were still aired as the Labvakar team enjoyed silent support across Soviet structures.

"We were filming. The Soviet police stopped us and took us to the building that now houses a bank by the Freedom Monument. The director, the operator, as well as me and Edvīns were taken to the second story where, it turned out, a Cheka recording studio was located. They were filming the goings-on by the monument. Then a high-ranking police official went by and screamed at the policemen that we're from Labvakar. We were promptly released. Then we went to the studio and edited the material. If I'm not mistaken, Central Committee representative Daudišs visited us to review the content and said it can't be broadcast. [..] Of course, we did, and were later reprimanded," said Rubenis.

Fake scripts

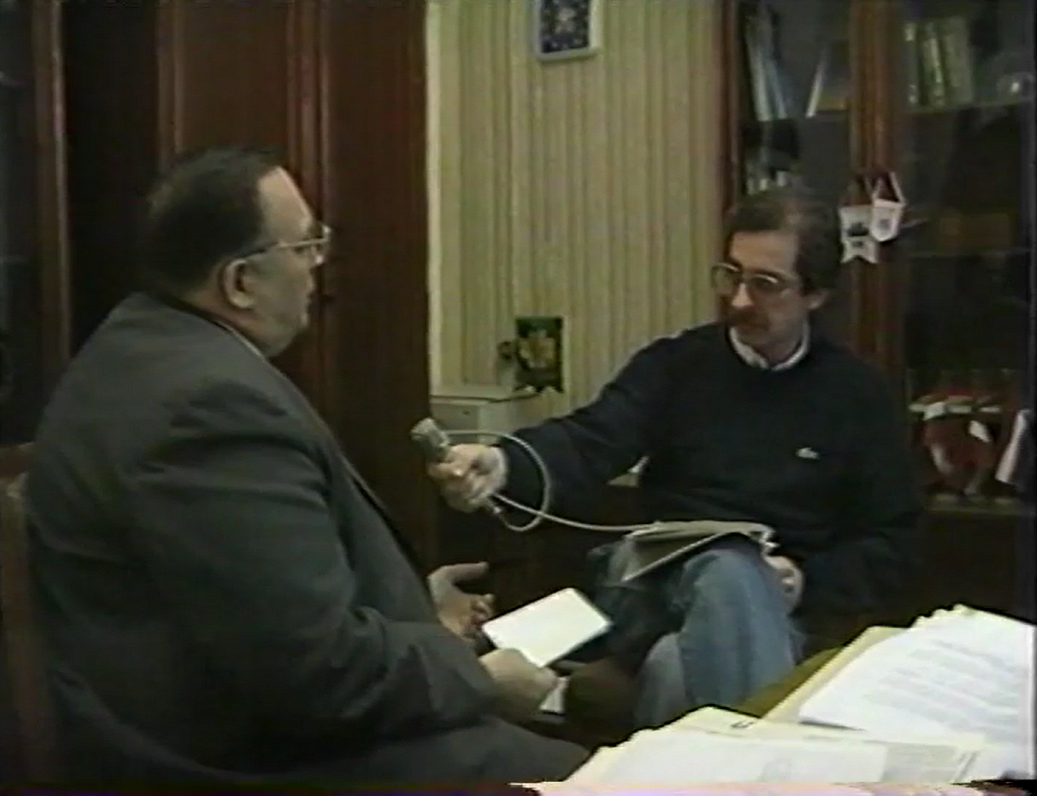

Rubenis likewise remembers that there were many direct encounters with censorship officials. Every broadcast had to be run by the Main Directorate for Literary and Publishing Affairs, or Glavlit, for short.

He recalls a very loaded conversation he had with a censor in the 1980s. "There were many restrictions. You couldn't film just anywhere [..]. We sat down at a table and she said, 'Comrade Rubenis, I can't sign a script like this. You can't do it. If you want to air the program on Sunday, I suggest you do this.' Then she waved her hand above a paragraph, indicating that this topic should be removed. She continued: 'You understand. It's now Friday noon. I'll be here until four,'" Rubenis recalled.

And understand I did. I ran to the television and cut the script from twenty pages to eight. I took it back to her and she quickly signed it. But the thing we aired was wildly different. I did mark the topic. For example, Edvīns would talk about the Soviet Army's actions against Finland during the Second World War. But we didn't say the content would be critical," said Rubenis.

Self-censorship allows working under a repressive system

Of course, the next day LTV director Jānis Leja received a call from the Central Committee. He summoned the journalists to send them off to the committee for review, but he reminded them to agree to everything that's said as it was clear that a broadcast enjoying such public support wouldn't be shut down just like that.

With hindsight, the people at the broadcast say that their work was characterized by a sort of self-censorship that allowed them to tackle forbidden topics. Fear was a big motivator too.

"Communism had a lot of experience in shutting out people who think different. Through Latvian history there were such examples in almost every family. People were afraid. And you knew that you represent them. That they think the same way," said Šipkēvics.

"You have to realize how far you can go so that you had room left to detach from the situation unharmed. We had sufficient self-censorship so that we could know how and when to go about discussing things," said Rubenis.

* The Latvian Radio story was created in cooperation with the Baltic Centre for Media Excellence. Thanks to the National Library of Latvia.