In the year of the 30th anniversary of the Supreme Council vote to reinstate Latvia's independence, a Latvian Radio strand looks back at the role played by the media during the National Awakening – this time, the story concerns Latvian Television news in Russian.

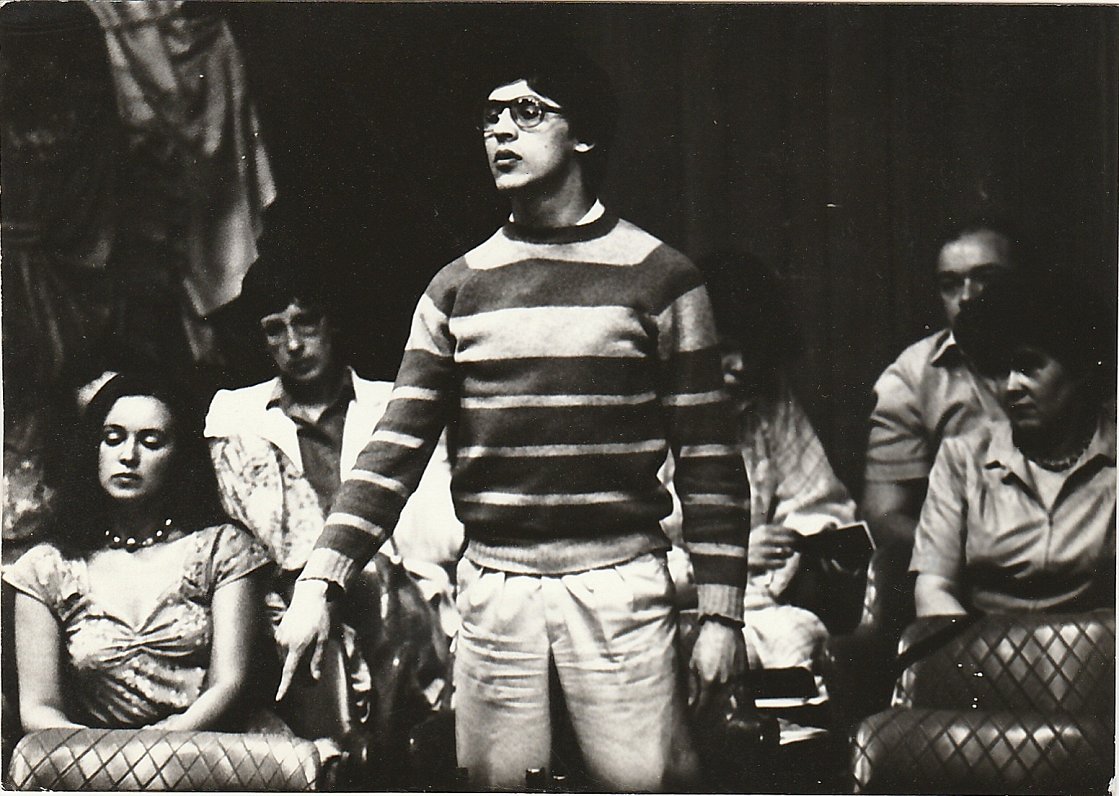

Alexander Mirlin (Latvian: Aleksandrs Mirļins), initially a print journalist, joined Latvian Television in 1982. He wrote stories for the Valoda tuvina (Language Brings You Closer) broadcast, which promoted integration. While in 1986 he started working as a non-staff employee, collecting and translating content for the television's Russian-language news broadcast.

"In truth, the news in Russian was another product made by the Panorāma journalists, as I think that most journalists realized that understanding and knowledge about current events is likely to differ depending on the language of the audience," said Mirlin.

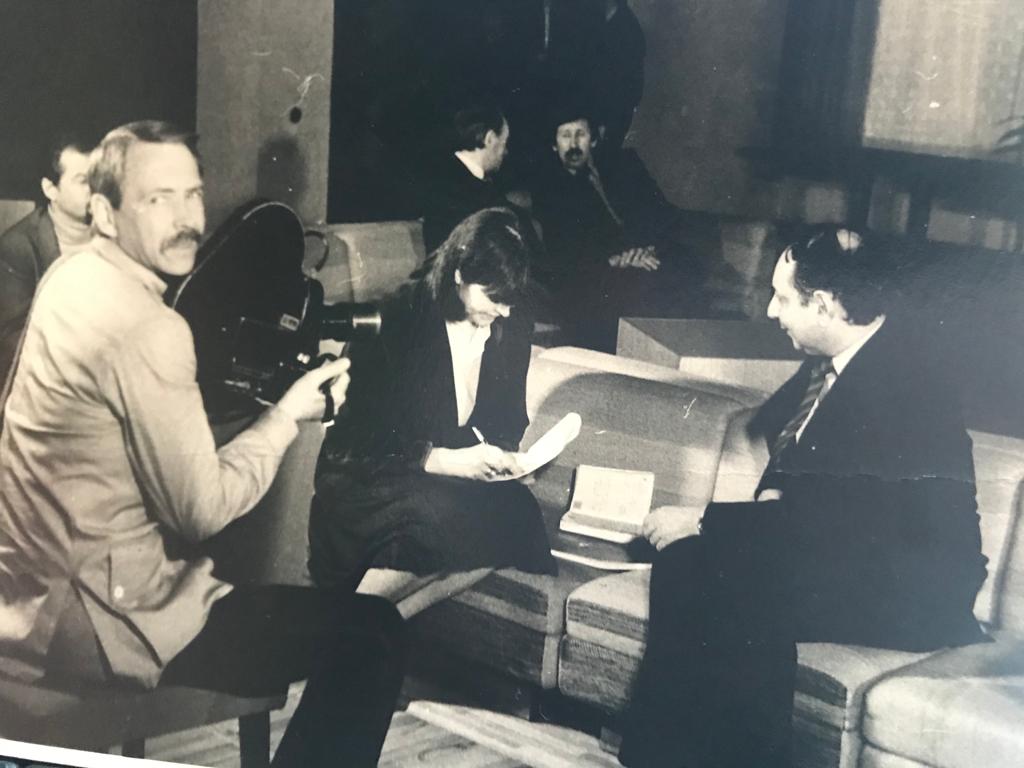

The Panorāma evening news show had a 30-minute slot, while Russian-language news were broadcast in 15-minute segments before 7 p.m. and before 9 p.m. Editors had to present the news scripts to the censorship office, Glavlit for short. It was a folder of documents, or the 'broadcast folder' as they called it. News would be censored before airing.

"You couldn't air a program if the broadcast folder didn't have a Glavlit stamp, but you could be rather vague in what you showed them. There was a black book that contained general guidelines for the censors. These had a list of what you can and what you can't tell in the media. There were strategical limitations – you couldn't broadcast panoramic shots and videos.

"As for political limitations, you couldn't talk about the interbellum independent Latvia. You couldn't mention politicians, some writers and artists, as well as some events from the independence. As political life geared up, the Glavlit couldn't keep up as the black book didn't say you can't mention the Popular Front or Latvian sovereignty. I think that the censors were unable to keep up with the changes and thus the institution that is Glavlit lost its power," said Mirlin.

Mirlin thinks that, as a consequence, the biggest critics and censors were the public itself, as the public could phone editorial staff to give their own view about what they'd just seen on television.

"In 1988, when Jānis Ķipurs became the bobsleigh champion in the Winter Olympics, it was clear that we, the Russian news and Panorāma, as well as the printed press would call Ķipurs a Latvian athlete representing Latvia. We made a story about that, but we didn't have a picture, there was just the video filmed by the Moscow television. There, Ķipurs stood on a pedestal with a Soviet flag.

"We received two types of calls. Some asked, 'Why are you calling him a Latvian athlete if he's from the Soviet delegation?'. Still others asked why we were showing an athlete with a red flag, seeing as he's from Latvia. So I would say that the powers of the authorities waned rather quickly, but there was control on the part of the public. As a great part of the population saw current events without having a historical context, I think that Russian-language news were very important back then," said Mirlin.

Velta Puriņa, a former journalist at Panorāma, said that Russian-language news were made in tandem with Panorāma and local Russian speakers weren't pushed away from the ongoing changes as the television broadcast stories critical of the Soviet Union as well.

"There were, of course, more people working in Panorāma, but the most important stories weren't interpreted or made differently in the Russian version. The information space was of a good quality. The mistakes were made later on, when the public were divided in their hopes. But support was great from Russian people as well," said Puriņa.

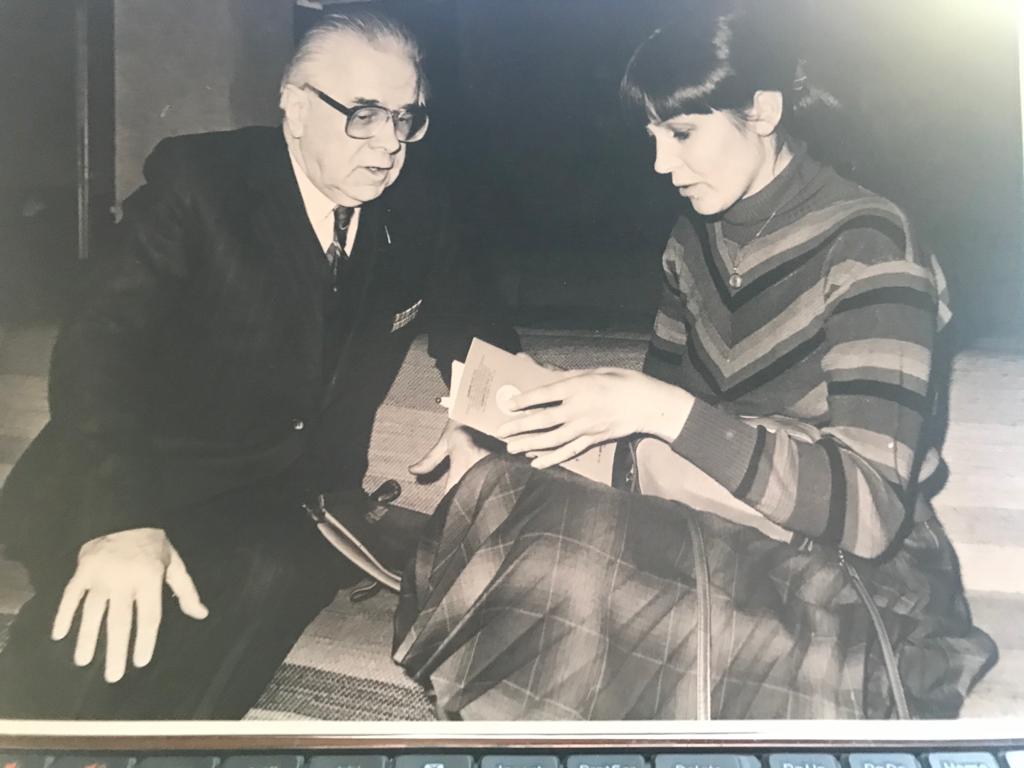

Puriņa said that changes were brought in the Latvian news desk with the new Saturday Panorama show that was introduced in 1987. It was a review of weekly events but instead of a talking head it featured different journalists. She remembers that the show was considerably more relaxed than the news broadcast, allowing to discuss things that were banned from the news.

Of course, the leaders of the Latvian SSR and the communist party also followed the Panorāma news show, and they would often complain to the editorial staff.

"Every Monday, meetings were held with the editor-in-chief, in which they pointed out mistakes. I think it was more of a symbolic act, even though some journalist would react with anger and disbelief. Looking back today, I realize it was just words. 'Comrade Puriņa, how could you not know? Where do we live?' – to which I answered, 'In Latvia'. This was followed with: 'No. It's the Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic. How could you not know where you live?'

"It was a tribute to the people who oversaw the television, who had the power to fire someone, and so on. It was evident that you could do more, that you could air stories about the people in power," said Puriņa.

A telling example of how journalists tested the boundaries of the permissible is Mirlikin's story about Lāčplēsis – a mythical Latvian hero – on Russian-language news. According to Mirlikin, in 1989 the Russian-language news desk was able to broadcast fragments of the 1930 film Lāčplēsis by Aleksandrs Rusteiks. It was for a TV a story about the November 11 – Lāčplēsis Day is the day upon which Latvia's soldiers are honored, and the film featured both scenes from the mythical past and the Freedom Battles of 1919.

"You could not even mention the film, let alone broadcast it," said Mirlikin. After obtaining permission from the editor-in-chief, he went to the archives and was able to have the film transferred to video. "It was a significant thing as we copied all of it and broadcast fragments on the Russian-language news and Panorāma. A few days later, television people aired the entire film."

Both journalists say that the National Awakening wasn't really on anyone's agenda. Instead, it was a process that concerned families and their acquaintances, and the media invested into both information spaces.

"Journalists had a big role in promoting self-awareness. International solidarity among journalists over Latvian independence was important as well, and people defended journalists and stood up for freedom of speech. I don't think we can consider journalists' contribution separately from that of the public itself. Journalists and the people were bound together very closely indeed back then," said Puriņa.

*This Latvian Radio story was made in cooperation with the Baltic Centre for Media Excellence. Thanks to the National Library of Latvia.