Fascinatingly, the documentary hears not only from the victims of the Cheka's unwanted attentions but from former KGB men themselves, who explain and in most cases try to justify their actions thirty or forty years ago.

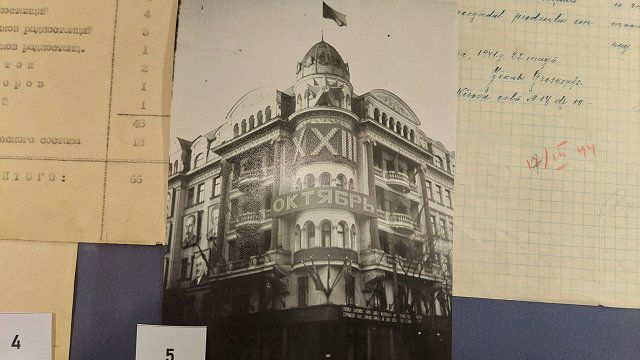

Mixing new footage with judicious use of archive material, Lustrum centers on the former KGB headquarters in Rīga, the so-called "Corner House" while it undergoes renovation, but also moves through the streets of the Latvian capital, the homes of interviewees and the places where they were approached by the KGB, offering inducements, thinly-veiled threats and in many cases, both.

Those taking part include former Prime Minister Ivars Godmanis, poet and lyricist Janis Peters, poet Janis Rokpelnis and dissident Lidija Doroņina-Lasmane, whose quiet piety gives a core of dignity among all the stories of moral compromise and lingering shame.

Lustrum is directed by Gints Grube and written by Grube and investigative journalist Sanita Jemberga, who previously worked on the documentary Master Plan. LSM spoke to Sanita about working on Lustrum.

Sanita Jemberga on documentary film Lustrum

Lustrum will be premiered on November 8, 2018, within the framework of the National Cinema Festival "Great Kristaps", with parallel premieres of the film in other cinemas throughout Latvia, where, discussions of the legacy left by the KGB in different places in Latvia will be encouraged.

LSM editor Mike Collier attended an advance press screening and gives his thoughts on the film below.

Lustrum is an excellent documentary and benefits from a cool, detached treatment that is free of the prodding and didacticism of some documentaries dealing with this subject matter, which understandably tends to provoke strong emotions in both participants and the audience.

The use of archive footage is ingenious. Subtle treatment of modern footage so that it bears some of the stylistic traits of older material gives old and new images a certain unity so that the gray men in suits we see in fuzzy images from the 1980s seem not so different from the gray men in suits deciding the future of the KGB archive in very recent video clips.

The real emotional core of the film is the testimony of those approached by the KGB, explaining how this happened and how they reacted. Some admit a degree of complicity, some do not, and it is to the immense credit of the film-makers that they restrain themselves from intervening to underline truths or lies. It is a very adult and emotionally mature approach in which people are seen not as simple heroes and villains but as individuals trying to make more or less moral choices in a society where moral choices are extremely difficult to make and come with serious consequences. As the dissident Lidija Doroņina-Lasmane (whose quiet dignity is a powerful presence throughout) points out: "It was not a system that allowed you to stand on the sidelines."

In another great section, the writer Mara Zalite recounts how a friend tried to persuade her that cooperating with the KGB wasn't anything to be ashamed of and that "The Cheka today is not like they used to be, all repressive. They are the good Cheka!" As Zalite and others then point out, refusal to cooperate soon saw the "nice" Cheka adopting a less amenable attitude.

From this distance it can be difficult to understand exactly how pervasive the Cheka presence in Latvia was, but it emerges in the film from telling little details. As journalist Ojars Rubenis recounts of his first encounter with the KGB: "They knew everything about me, about my family - when my mother left the house and came back. They knew more about my life than I did." And this was in the pre-internet age when "tracking" someone meant more than having spyware on their computer. It meant people were watching.

The other significant innovation of Lustrum, and one that may ultimately be of even more historical worth than the testimonies of those targeted, is giving a voice to the former KGB men themselves. Clearly their testimony is often far from reliable but in many cases does have the ring of truth, with one anonymous interviewee who speaks only by telephone coming across as particularly credible when he describes the internal politics of life within the organization.

The testimony of the KGB men throws up numerous ironies, from them complaining that they just want to be allowed to live their lives in peace to a certain pride they take in having associated with prominent figures in the independence movement. And perhaps the most remarkable revelation of all is that, despite their initial protestations that they will not speak to journalists or film-makers, once they start they cannot stop. At times they sound like nothing so much as gossiping old women on washing day - and the viewer cannot help wondering if perhaps this psychological trait, the need to feel like they are important and at the center of whatever is happening, may at least partially explain why they followed the career path they did.

Non-Latvian audiences may find themselves struggling with some of the details and historical background, particularly the complex debate about whether or not to publish the KGB archive material, so it is to be hoped the promised English-language version comes with suitable explanations for those unfamiliar with modern Latvian history.

The tendency to jump backwards and forwards in time can also be slightly confusing, but this is a minor criticism and is simply the way in which the film-makers have chosen to tell their story via a series of personal interviews and memories rather than a more impersonal chronological sequence.

Lustrum works as film, as investigative journalism and as historical document. It is a mature, thought-provoking and sometimes touching film that treats both audience and subject matter with due respect. I strongly recommend seeing it if you get the chance.