After some historical facts, we'll present summary results of a recent public opinion survey and then reproduce the first in a series of five contrasting personal opinions about May 9 and the monument, with the remaining personal opinions to be published on August 25 and 26.

The views expressed are personal and some may find them incredible or even offensive. Nevertheless, they are the opinions of individual members of the public, and do not represent the views of Latvian Public Media.

Soviet Victory Monument Timeline

Following World War II, 9 May is declared Soviet Victory Day in the USSR, a tradition which continued in the Russian Federation and several other CIS countries. From 1965 it was a public holiday.

5 November, 1985: A monument dedicated to the "Soviet Army - Liberator of Soviet Latvia and Rīga from the German fascist invaders" is unveiled in Riga.

9 May, 1990: Soviet Victory Day on 9 May is the last time Victory Day is officially celebrated in Latvia, and it loses its status as a public holiday.

9 May, 1991-1994 becomes the Day of Remembrance of the Victims of the Second World War in the Latvian calendar of public holidays and commemorations.

1994: The Socialist Party of Latvia takes the initiative to revive 9 May celebrations at the monument.

1995: On 6 April, the Saeima amended the Law on Public Holidays and Days of Remembrance adopted by the Supreme Council of Latvia, removing 9 May from the calendar as Remembrance Day for the Victims of the Second World War and introducing 8 May as "Day of the Defeat of Nazism and Remembrance Day for the Victims of the Second World War".

1995: Russia adopts a Veterans' Law guaranteeing social privileges for war veterans in the pension and welfare system.

9 May 1995: For the first time since the collapse of the USSR, a military parade is held in Red Square to mark the 50th anniversary of Victory, a memorial on Prayer Hill and a monument to Marshal Zhukov is unveiled. On the same day, around 11,000 people, including many schoolchildren, gather at the Victory Monument in Rīga. The event was chaired by Socialist Party Vice-Chair and MP Filips Strogonovs.

9 May 1996: The Latvian Saeima adopts a law designating this day as Europe Day, as it looks toward eventual European Union membership.

1998: The 9 May celebrations at the Victory Monument in Rīga are organised for the first time by the Party "For Human Rights in a United Latvia".

2001: Russia adopts a program of 'patriotic education' for its citizens, which is implemented through the mass media.

Since 2000 Stalin's popularity as a historic Russian leader among the Russian public grows again.

2005: The Russian Federation celebrates the 60th anniversary of the victory in the 'Great Patriotic War', with world leaders including Latvian President Vaira Vīķe-Freiberga; for the first time, a mass action "St. George's Ribbon" is held, and this ribbon becomes a special symbol of Russia.

2005: The scale of the 9 May celebrations is growing, with 260,000 people taking part in the festivities in Riga, according to press reports, and the celebrations begin to take on the character of an open-air festival.

2006: In Latvia, the George ribbon appears on clothes and cars, demonstrating belonging to the Russian state vision of history.

2007: In Tallinn, Estonia, the relocation of a monument dedicated to Soviet soldiers from the city centre to a military cemetery sparks riots.

2008: Military parades are resumed at the Victory Day military parade on 9 May in Moscow's Red Square.

2008: In a survey conducted in Latvia, 62% of people say they do not want the monument in Victory Park to be demolished.

9 May 2008: The celebration is organised by a satellite organisation of the "Harmony Center" party alliance - the 9may.lv association, and is intensively promoted on the PBK television channel.

2010: The main organisers of the 9 May celebrations are the political party "Harmony Center" and its satellite organisation 9may.lv.

2014: Around 39% of Latvian residents celebrate 9 May, which is not an official day of commemoration or celebration in Latvia.

9 May 2014: Following the invasion of Ukraine, the Moscow 9 May Day parade is no longer broadcast at the Victory Monument in Rīga, and the organisers announce that they will not distribute George ribbons.

2015: About 33% of the Latvian population watches Russian TV channels in Latvia. 26% of respondents to a survey say they have celebrated 9 May in recent years (7.5% of Latvians and 65.8% of Russian-speakers).

9 May 2015: For the first time, around 200 people march to the Victory Monument in Riga in the so-called 'Immortal Regiment March', a tradition taken from the Moscow Victory Day celebrations.

9 May 2019: 4,000 people march in the Immortal Regiment, carrying pictures of soldiers who died in the Second World War.

15 November 2022: is the date by which it is decided to demolish the monument to the Soviet Army in Victory Park, Riga.

Public Opinion

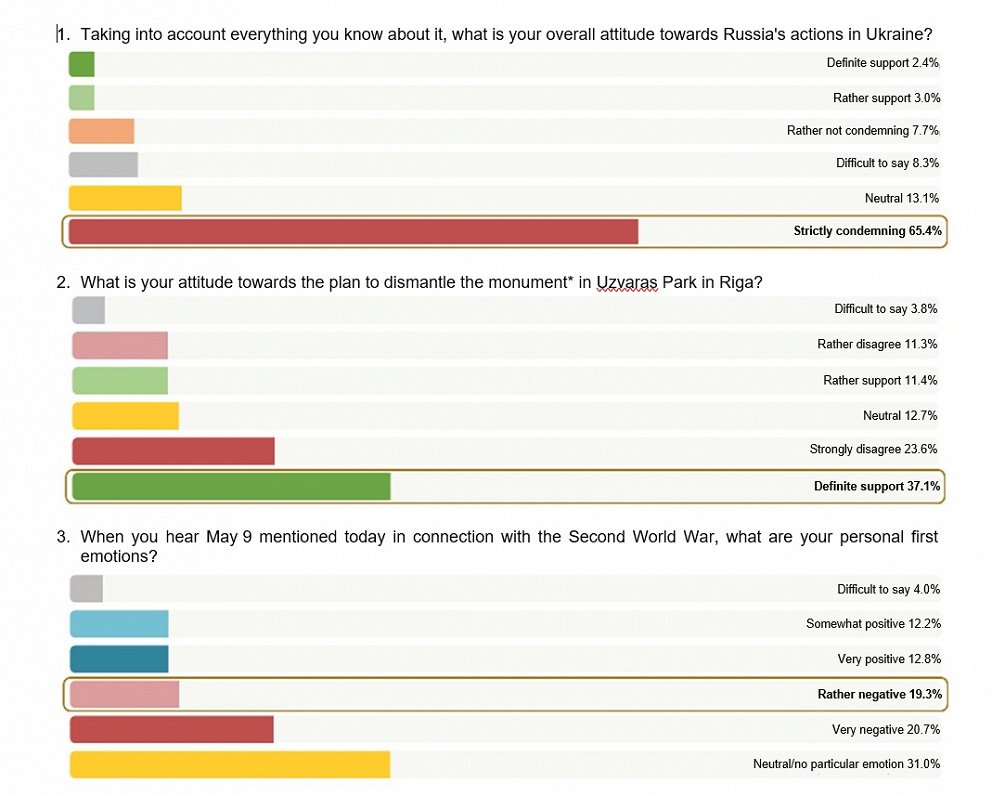

In June this year, the SKDS pollster carried out research for LSM into public attitudes toward May 9 and the Victory Monument. The data was based on a sample of 1,396 Latvian residents aged 18-80 years from both Latvian-speaking and Russian-speaking households. Some summary findings are presented in the graphic below.

Russia's invasion of Ukraine and its barbaric actions there have undoubtedly been the main cause of a groundswell of opinion in favor of demolishing the monument, with many people arguing that there is little or no difference between the Russian Federation's war crimes in Ukraine and the Red Army's actions in Latvia, so leaving a monument to those actions in place is offensive.

Yet the SKDS research showed that among Latvian residents who speak Russian in their families, a part (40%) condemn Russia's actions in Ukraine, but the majority of them (60%) do not support the demolition of the Victory Park monument.

Among Latvian speakers, opposition to Russia's war in Ukraine is much clearer, and so is the belief that it's time for the Soviet memorial to come down. In the first of our opinions from members of the public, below, we'll meet someone who shares that view.

Personal View

Armands (47): "Latvia will be free when the monument is demolished"

Armands (47), artist, born and raised in Pārdaugava, Rīga, mother Russian, family spoke Latvian

I have never celebrated and do not celebrate 9 May. 4 May? Is it the White Tablecloth Holiday? I don't celebrate any holidays. Back then, when I remember the first gatherings at the monument - they were less politicised - people met, but without consequences. It was on the news that day, but two days later it was no longer talked about. I don't remember any acts of vandalism or protests. It was a one-day celebration.

I remember that in the 1990s the "Pērkonkrustieši" [an extremist nationalist group] wanted to blow up the monument. Unfortunately, they didn't. It is a pity that it didn't work out then. And I regret even more that the State was not able to deal with the issue even then. It seems absurd that people now have to donate money for demolition, and only when the money has been donated does the State act. Once a friend and I were talking about blowing up the monument ourselves, but my friend refused.

The family didn't talk about the history in details - I only knew that both my dad's and my mum's aunts had been deported, but I didn't know that the family had ever owned property until the 1990s. The background mood in the family was that all Russians were bastards, the bad ones. In Soviet times, the bicommunal state was much more pronounced. I remember there was a hustle and bustle and intolerance with the Russian children but nobody really knew why. The Russians didn't speak Latvian, maybe that's why.

I was going through old magazines in the attic - there were old "Atpūtas" [a travel and recreation magazine from the first period of Latvian independence] for example. I knew that Latvia was free because my grandfather had his own bakery before the war. It wasn't really called the free Latvia, but rather it was the time when the family had its own bakery - before the war. In order not to be deprived of the family home, the family sold the half of the house before the war or at the very beginning of the war. No-one in the family celebrated or talked about 9 May, no one associated the word "victory" or songs about victory from films about the German defeat with the loss of Latvia's independence. Occupation or independence were words I learned in the 1990s.

The Monument. I remember when I passed the monument on tram 10, when it was being built, there was a high fence, they were doing something, they were building for a long time. There was a black-and-white film made about the monument, where the author talked about the characters - the mother and the soldiers. I went to a ceramics class, which is probably why I remember this film. I remember that at the beginning there was an idea that the mother would have a child in her arms - I don't know if it was real or not. I didn't go to the opening of the monument, but I asked my mother what was going on, and she just said that forced donations were collected at work for the building of the monument. She complained that the whole work collective was forced to donate. I found the monument interesting - a tower with stars. I didn't like the bronze statues because they had no energy, they didn't evoke any emotion. But the tower, though, with those five stars, had great energy - I thought it was interesting and good.

A year or two ago, my first feeling was - why is this monument still here? What is it doing here? How can this be? Looking at the monument, I couldn't understand why no Latvian since the 1990s has bothered to blow it up. Associated with the Soviet legacy, not victory, glorification or 9 May, but with what was left here after independence from the Soviet era. There were no such emotions in Soviet times, but only afterwards. Because the monument does not conform with our freedom. In Soviet times there were two languages, a lot of Russian - at the time I couldn’t be bothered but when Latvia was independent, then this monument should have disappeared a long time ago, along with the street signs that were in two languages.

Today the decision has been taken that the monument must disappear, but I do not understand why it cannot be blown up in public? Why do we need millions to tear it down? It should be blown up in a controlled way, but in the meantime the decision-makers are counting the money. At the same time, all sorts of Russian nationalists are coming out of the closet again, because the more you stir shit, the worse it stinks - are they defenders of the Russians, or is it just the election coming up?

I want this monument to be demolished, without a doubt, so I understand those who want to demolish it, but I am afraid that this will once again be a reason for political forces to use to appeal to their electorate. I understand those who do not want to demolish it - it is important for someone, but I do not understand what such people are still doing in Latvia. Where could they have come from 30 years after independence? Clearly, this is the consequence of a politically constructed bicommunal state. Who has been to war? Who remembers? Grandfathers who are no more? I did not donate to the demolition of the monument. Marches against the Soviet legacy are, in my opinion, superfluous, and I do not participate in them. When the monument is taken down, Latvia will be free. I believe there will be one less tumour.

24 February. I remember that the night before the war broke out, I came back late from a workshop in Lithuania, so I slept late in the morning. I remember that day very well because I was in great shock when I heard what had happened. I didn't leave the TV all afternoon. I was shocked that it actually happened. But today I am disturbed that this has dragged on for so long and that there are so many supporters in Russia, both for the war and for Putin himself.

To carry out an order, there has to be some support among the executors; it is not a one-man show, as I thought at first. It is widely supported in Russia. Clearly, the authoritarian regime there has achieved its goals. In Soviet times we imitated the friendship of the peoples, that we were for communism, but I am shocked that the Russian post-Soviet people are still zombified and their support for the war is genuine. On the second day of the war, at the school where I worked, my pupils and I made a three-metre poster and drove to the Russian Embassy to express our disapproval of what had happened. A few days later, we took part in a campaign with the children, drawing posters and protesting right in front of the Russian Embassy.

I still follow what's happening in Ukraine on a daily basis, and I have become a regular follower of political commentators on the internet, which I used not to do: I used to follow a Ukrainian gardener and listen to gardening tips. I am not afraid that war is imminent for Latvia, and we have no plan or agreement on what we would do if war broke out. I have no friends in Ukraine, but I have relatives in Russia who think that Putin has started a senseless war without any certainty of victory. I always stress that there is no objectivity anywhere, and that is why I try to talk as little as possible about the war. They also believe that there are many real nationalists in Ukraine, giving a negative connotation to the word, and that Ukrainians themselves are to blame. I am wondering, because I associate nationalism with patriotism, not extremism. It is normal that people are in favour of their country and support it. They confuse Nazism with nationalism. Yes, we talk in the family about aggression that has been started for no reason, which is not acceptable to anyone, and we explain it to our children.

There are no coincidences - everything is connected, the monument has the most direct link to the war in Ukraine. The Soviet cult outside Russia is Soviet chauvinism instead of putting flowers on your grandfather's grave. Living in a foreign country, while showing loyalty to another aggressor country is dividing society in Latvia.