Conscripted by a foreign power

Only a week had passed after the first Red Army soldiers crossed the Latvian border. The Soviets controlled the northern and eastern parts of the Latgale cultural region, whereas the major cities of Rēzekne and Daugavpils were still under Nazi control. The situation was far from being stable, and as of yet there was practically no Soviet bureaucratic power in occupied Latvia to speak of. But the higher-ups of the Red Army did not want to listen to any objections from the bureaucrats of the Latvian SSR. The Red Army needed every soldier it could have, and on July 26, 1944 the War Commissariat of the Latvian SSR was ordered to immediately start the conscription of every man born between 1895 and 1926.

Throughout the next month, the local Soviet commissars scrupulously handed out conscription notices to almost every man able to work. This was often coupled with confiscating the would-be soldiers' passports and reminding them that they have to arrive at the conscription point after three days.

Only the most fervent supporters of the Soviet ideology were ready to defend it with their lives. Most of the rest were not enthused by the prospect of fighting a foreign war. In addition, by becoming soldiers they would leave their homes right before harvest time, which would have ensured nourishment throughout the coming winter. Fighting for the Red Army was directly opposed to the conscripts' personal interests. For many, these personal reasons were supplemented with varying degrees of nationalist sentiments and a sense of duty against the country they had so recently lost.

Those who were in a position to do so chose to ignore the conscription notice, while of those who couldn't about 20% soon deserted.

Resisting conscription as well as desertion was, of course, a grave crime in the eyes of the Soviets. But for the first months at least the occupation powers lacked any resources to make locals obey their laws. As a result, most of the men who had remained in Latgale in late summer 1944 were left in a grey zone, legally speaking. They were officially criminals but practically speaking they could resume their lives as before, with the proviso that they had to avoid Soviet activists as well as they could. Events unfolded similarly in the regions of Vidzeme and Latgale that were affected by the occupation.

Attempts at punishment lead to active resistance

But back then, draft dodging did not equal being ready to engage in armed resistance. Those whose main motivation was hatred against the Soviet regime had joined the Latvian Legion a year ago, voluntarily. However, of the nationally-minded deserters, but a few were tied to the Latvian Central Council or any other national resistance movement. (Read more about the early anti-Soviet resistance in Latvia.)

But the situation gradually changed with Soviet attempts to impose the laws they had made in the occupied territories. In fall 1944, the first attempts to punish the deserters were recorded across several Latvian parishes. Local police or army departments raided suspects' houses, and the first confrontations ensued. The authorities usually used force and menace, whereas the suspects hid and fled, often being chased by gunfire.

But in some cases armed men greeted the authorities' arrival, and the first armed skirmishes took place.

As the situation became more and more intense, more and more men who had dodged conscription came to the conclusion that cooperation is needed and that they should become more serious in hiding their traces. Accordingly, the first anti-Soviet resistance groups sprang up in northern Latgale and eastern Vidzeme. Becoming more organized, the partisans could muster more effective resistance. This meant more police and soldiers died. Local commissars were at a loss, and the NKVD – People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs – became involved in the fight.

In October 1944 the NKVD started the first coordinated actions against the partisans in northern Latgale. But instead of the expected successes the Cheka initially faced one defeat after another. The partisans killed several NKVD agents and organized the first successful attacks with the goal of freeing prisoners. But the NKVD carried out "punishment expeditions" in response. In the last months of 1944, the clashes between Soviet forces and the partisans were something akin to small battles.

The national resistance is born

Until this point, most partisans evaded being drafted into the Red Army for personal reasons. They didn't want to fight and were wary of leaving their relatives without support. But national ideas grew more and more popular as the resistance turned into an organized struggle from sporadic individual initiatives. Partisan groups merged with the existing structures of the national resistance movement and assumed its ideas. Some partisan units in northern Latgale and Vidzeme became part of broader organizations, such as the Latvian National Partisan Union and the Fatherland Defense Union. These organizations wanted to reinstate Latvian independence.

By early 1945 the partisan organizations of northern Latgale started to resemble tiny armies, with broad support and an impressive number of soldiers.

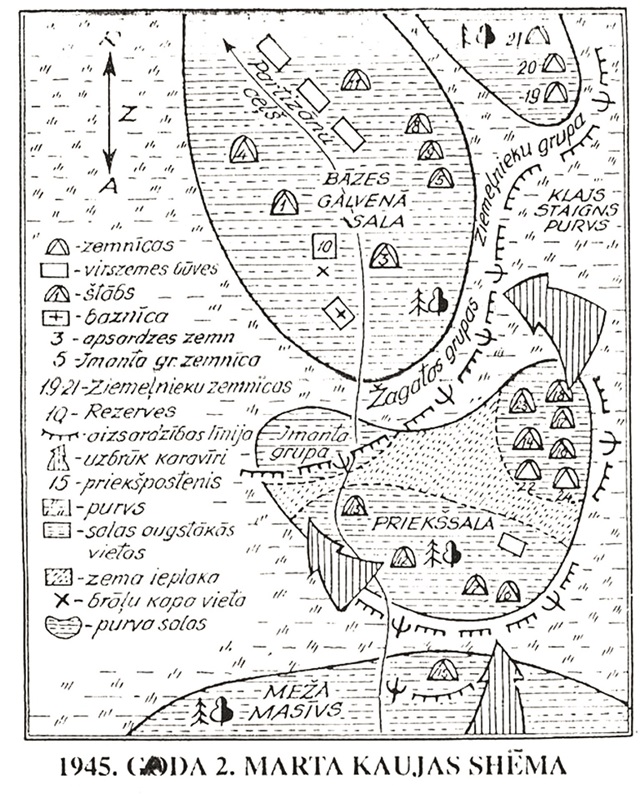

There was no safety in numbers, however. A battle at the Stopmaku swamp proved this in a tragic way. Partisan leader Pēteris Supe had created a great partisan camp inhabited by about 350 people. It was too big to escape Soviet notice, and on March 2, 1945 it was attacked by Soviet forces. 28 partisans and 46 Soviet soldiers died. Even though most of the partisans were able to escape, from now on the organizations played it safe, separating themselves into small units that oversaw the areas in their vicinity.

Independence hopes

After Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945, the second resistance center – Kurzeme – came under Soviet control. About 4,000 legionnaires did not surrender to the Red Army and instead opted to become partisans. Despite Soviet hopes to the contrary, partisan units arose in parishes of Zemgale and Vidzeme, where the Reds hadn't witnessed armed resistance hitherto.

In summer 1945, the partisans had become a national movement involving about 20,000 Latvian residents directly and tens of thousands more ready to support them morally and materially.

In addition, there were also comparable resistance movements in Lithuania and Estonia as well.

As the resistance movement was so great, in 1945 many partisans really did believe that they could reinstate an independent Latvia by means of armed struggle. Hopes for intervention by the Western powers also seemed realistic. Partisans hoped either for the start of a World War III, or that Western help would firmly establish resistance to the effect that Latvia would be liberated from the Soviet yoke.