Latvia does not celebrate Victory Day on May 9 not only because the end of the war brought it years of occupation; it's because there was more war to come. There were about 500 groups of partisans on Latvian soil, with around 20,000 fighters and as many supporters. Thousands were to fall in the fierce battles of the following years. The Soviets did not prevail with the sickle and hammer. They resorted to bullets and scaffolds instead.

Fiercest fights in Latgale

While the Forest Brothers fought across the entire territory of Latvia, the first skirmishes with the partisans took place in summer 1944 in Latgale as the Red Army crossed the Latvian border. These were mostly small, uncoordinated resistance groups, as Latvia's underground movement never had a unified leadership.

Nevertheless, the Abrene administrative region had the largest and best-organized partisan network. They called themselves the Latvian National Partisan Union.

The group started in the way it would in a spy film. On October 1, 1944 a German intelligence plane left an airfield in Eastern Prussia. It flew across Latvia and dropped three groups of paratroopers behind enemy lines. The Russians destroyed one of them, and there's no information about the fate of the second one. But the third took shelter near Baltinava – a municipality on the current border with Russia.

What was surprising is that these groups were comprised of Latvians and they weren't planning to collect intelligence for the Nazis. Instead, they wanted to organize a resistance movement.

The group's leader was 24-year-old Pēteris Supe, a former agriculturist and member of the mazpulki youth organization, similar to 4-H. He had been inspired to fight by the March 1944 memorandum by the Latvian Central Council that called for Latvian independence.

Supe was reportedly clueless about military issues and therefore applied to serve at a German intelligence unit.

Wintry skirmish proves direct warfare useless

A few months after landing in Latvia, in December 1944, Supe called together seven partisan groups, 123 men in total, to create a resistance unit. It was operating across large swaths of the Vidzeme and Latgale cultural regions, with membership quickly reaching 1,000. They planned to launch winter resistance offensives.

In January 1945, Supe's men started building a grand fortified residence for the resistance in the Stompaku swamp near the Viļaka river. It became the largest resistance headquarters in the Baltics. But a few pits remain now, but it was a veritable fortress back then.

There were armed guard posts, 24 dugouts, horse stables, a granary and even a bakery and church. The buildings were constructed on islands in the swamp, therefore the place was referred to as the Saliņu (little island) residence, or, in jest, as Little Berlin. About 350 people lived there, including women and children.

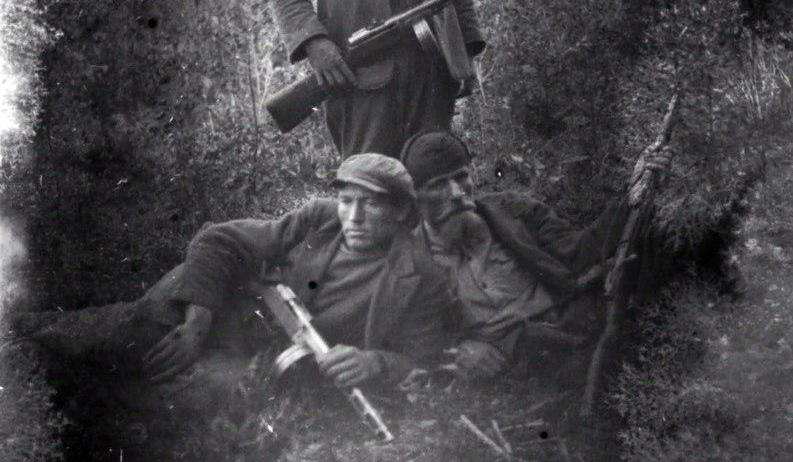

The fighters were, for the most part, young people. Some had deserted the Latvian Legion or the Red Army. For them, resistance was not political but instead based on the fear of persecution.

Those who fought near Abrene had another motivation: they were fighting for their homes, as part of Abrene was added to Russia's Pskov Oblast.

The Soviets had to go to war on two fronts, against the Nazis and against the partisans. Supe was a tough nut to crack. On March 2, 1945 about 500 Red soldiers and KGB officers started an offensive against the Saliņu residence. The partisans were able to prevail for 24 hours and then most of them took to the nearby forest. Meanwhile the offensive was recalled and Supe along with the HQ were able to remain in the reserve bunker.

The Stompaku battle is thought to have been the largest partisan fight throughout Latvia's years of resistance. It turned out relatively well for the resistance, but it proved that they didn't have the power to take their enemy head-on.

Instead, they opted for setting up mobile groups and fighting smaller battles.

Total war or mere savagery?

To add political weight to diversions, partisans opted to carry out their diversions on significant anniversaries. On May 15, 1945 – the anniversary of Kārlis Ulmanis' 1934 coup – Supe's men and Alūksne's Forest Brothers attacked the communist executive committee of the Mālupe village, occupying most of its territory. They assembled the locals, hoisted the red-white-red flag and sang the Latvian anthem. For good measure, they also attached a grenade to the mast. Meanwhile on November 18 that same year the Lutheran parish of Palsmaņi sang the anthem – it was banned – under preacher Paulis Birzulis, a partisan informant.

The Soviet authorities called the partisans bandits. From the vantage point of power, it was true, as partisans are by definition illegal and therefore criminals.

The history of Latvian partisans has not been researched in depth. There are stories about them committing savage acts against the local population. It is told that Supe had asked to warn any local functionaries and only punish those who resist. But there was no strict behavioral code among the resistance. In Šķilbēni a family was murdered as they had reported to the KGB. Grown-ups and four children. At Dūre parish, a teacher – she had been pregnant at the time – was murdered in front of her students. Her husband was then beaten to death.

Even though it wasn't a war per se, partisans operated under martial law. Their opponent was a cruel totalitarian regime.

Soviets combing the forests

The army and the KGB carried out anti-partisan operations across the entire territory of Latvia. There were 13 such operations in the Ilūkste region. In summer 1945 almost all the parishes in the region had paralyzed Soviet institutions, with homes and stores and administrative buildings destroyed.

In August and September 1946 there were 1,570 operations in Latvia, or about 25 every day.

These operations mostly took the form of "combing", i.e. soldiers went through the woods in huntsmen-like fashion. Often, horses that had belonged to the resistance movement were used to locate the partisans, because horses tend to retrace a road they know. However, traitors helped the Soviets the most.

Much like the horses, they led the Soviets to resistance hideouts or helped kill the partisans themselves.

Traitors were recruited from the midst of the Forest Brothers. As criminals, they were easily blackmailed: should they refuse cooperation, they'd be punished along with their families.

Traitor kills resistance leader

Pēteris Supe, the leader of the Abrene partisans, was killed by a traitor. This marked the fall of his entire unit. It took place on April 1, 1946 at the Jaunzemi household in Jaungulbenes parish. Oto Klucis, former Lieutenant Colonel of the Latvian army, lived there, and Supe and his deputy Henriks Auseklis had arrived there to ask Klucis to join the resistance. Supe was usually accompanied by three bodyguards, but this time only one of them was present, namely Jānis Klimkāns. As they were talking, he asked Klucis' wife for some milk and killed both Supe and Auseklis after returning with an automatic rifle.

Klimkāns had seemed very dependable. A local peasant boy and a graduate of the Rīga English Gymnasium, he had deserted both the German and the Russian army. But it turned out he had applied to work for the KGB, went to spy school and made it into the resistance movement undercover. Thus he became a very successful and obedient killer. In 1952 the KGB sent him to Sweden, tasking him to infiltrate the British secret service as the commander of the national resistance. As the Americans, Brits were eagerly following anti-Soviet movements in the USSR.

In London, Klimkāns apparently burst. At a Christmas event of the Latvian exiles, he started confessing. The British intelligence service duly arrested him and deported him to Latvia. He was reportedly thrown onto the shore of Kurzeme, western Latvia, from a boat. Fearing locals in Latgale, where he had served undercover, he settled down in Kandava, western Latvia, where he worked as a teacher and died of cancer soon after. The KGB had no use for an agent who had blown his cover.

But the corpse of Supe was publicly displayed in central Viļaka. A message was written on his chest: "The leader of the Latgale bandits."

Earlier, four dead relatives of Pēteris Supe had been displayed at the very same place. His mother, father, sister, and brother had been killed by the KGB.

"Legalization" offer

The traitors targeted partisan commanders. Without a leader, the partisans became scattered and succumbed to doubt, fear and blackmail. When it became clear that no Brits or Americans would come to help, fighting died down. It became a war of survival. Everyone held out for as long as they could. More and more of the Forest Brothers took up the KGB offer of giving up without punishment.

The so-called Alsviķi truce also involved a legalization offer. It was a unique case – the only during the Baltic resistance – when the KGB and the partisans agreed to a ceasefire.

It took place in September 1945 at Strautiņi, the executive committee of the Alsviķi parish. The KGB allowed even armed partisan groups to pass. The ceasefire lasted twelve days, as was agreed upon, but fighting recommenced right after. But a few partisans had agreed to give up, as the KGB would not satisfy their naive demands – free elections in Latvia, taking the deported people back from Siberia, and more.

The naivete of the resistance is illustrated by two manifests, disseminated by two partisan groups in 1945 and 1946. Both demanded a free Latvia and for the USSR to leave. The documents were rather primitively written, very different from the memorandum penned by the hardened politicians of the Central Council.

Most of the politicians had left Latvia, but the partisans were still in the forest. Both, however, had lost their battles by then.

The last of the Forest Brothers

Just like the Central Council, the partisans were doomed to fail before they even started, depending as they did on the idea that Western allies would wage war against the USSR. The West never seriously considered the option as they were allies of the USSR, not the Baltics. The 1949 deportations also did much to reduce the partisans' powers, as many of their supporters were sent away.

By 1956, over the course of 13 years, 2,500 partisans had been killed. 5,500 were arrested and about 1/10th of them received the capital punishment.

Some resistance continued until the Khrushchev Thaw, when the last lone wolves left the forest. The last group of the Latgale resistance "legalized" itself in 1957. It was the Mičuļi family, five people altogether.

Jānis Pīnups is considered to be the last of the Forest Brothers. He left his hideout at the Preiļi region, eastern Latvia, only on May 9, 1995. It was the first "Victory Day" after the Russian army had left Latvia.

But calling Pīnups the last Forest Brother would be as misguided as deifying the entire resistance movement. Pīnups had never been a partisan. He had simply deserted from the Russian army and hid himself in panic fear of persecution, until the army finally left Latvia for good.

"All this war-waging seemed pointless to me," he said. "Luckily, I did not have to shoot once during the war. I couldn't have killed anybody. I couldn't even slay a chicken."

While there might be sense in going to war if there are political goals, the Latvian resistance had no political management, so you can say that their fight was... belated. It was a desperate raid on a sinking rescue boat long after the ship itself had sunk.