Erasing European history

The Second World War was shocking not only for its brutality and sheer scale; the breadth and cruelty with which Communist and Nazi ideologues effectuated ethnic and social changes was something hitherto unseen. Starting with the 1933 forced famine in Ukraine and concluding with mass German deportations from Central and Eastern Europe in 1950, the process saw a horrendous culmination during the war.

The policies of these totalitarian states led to there being 12 million DPs, whose future was in the hands of allied politicians.

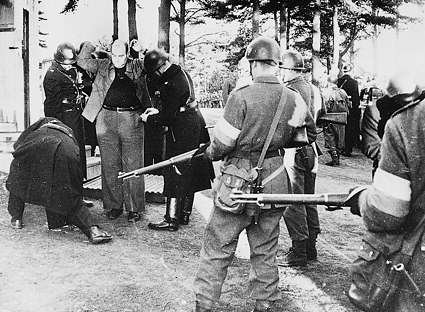

Among these 12 million was a veritable kaleidoscope of people. Some had just been freed from concentration camps; there were workers that had been forcibly taken to Germany; there were Soviet POWs; and Czechs and Poles that had served in Western armies; as well as civilians fleeing Soviet repressions. Then there were multinational soldiers who had fought for the Nazis; as well as collaborationists and war criminals. There were many ethnicities represented as well, with the French, Poles, Balts, Yugoslavs, Jews and Ukrainian Cossacks among the displaced.

Allied dilemma

As concerns DPs coming from the West, there was little doubt over how to handle them. These people wanted to go back home, as soon as possible. The only problems were logistical, as a lot of people were involved. In summer 1945, there were about 2.3 million French, 500,000 Belgian, 400,000 Dutch and 200,000 Italian soldiers there. But what was to be done with several million Europeans from the countries under the control of the Red Army? But a few of them were enthusiastic over going back. Many would have rather killed themselves.

The Soviet side stressed that their citizens are to be repatriated as soon as possible. The US and the UK did not object to this, in principle. But who was, and who wasn't a Soviet citizen? With the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, the USSR had illegally occupied the Baltics and Eastern Poland, and the Soviet delegation and the Allies had not yet reached agreement over the future of these territories.

In the first years after the war, it was not certain that a new Cold War was to come. The Baltic DPs had hopeful ideas about an upcoming war between the Western Allies and the USSR. On the other hand, there was fear that a treaty would be signed to send them home whether they wanted to or not. There were worrisome precedents in the French occupation zone: France's attitude towards the Baltic peoples was less positive than that of the US and Britain. Repatriating men who had served in the Nazi legion to the USSR was not unheard of.

Their own Constitution and University

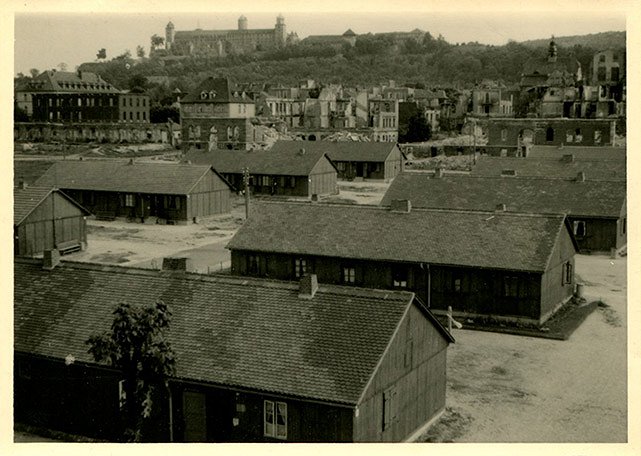

The DPs were stationed in special camps, with the first created as early as spring 1945. By the mid-year, Germany, Austria and the Benelux countries had a vast network of camps in place. People enjoyed privileges of self-determination, making the camps akin to "states within states".

The biggest Latvian camps were at Pinneberg, Eslingen, Zedelgem, and Föhrenwald. Most Latvian DPs were of middle-class origin. They were educated and experienced in administrative tasks, in addition to having good professional knowledge and cultural talents. Latvian camps became well-managed territorial and administrative units.

The Latvian camps inside the US and British occupation zones even shared a joint democratic "constitution".

It stipulated setting up committees of 15 to 20 people acting as parliaments which then selected the government of about 5 to 6 people.

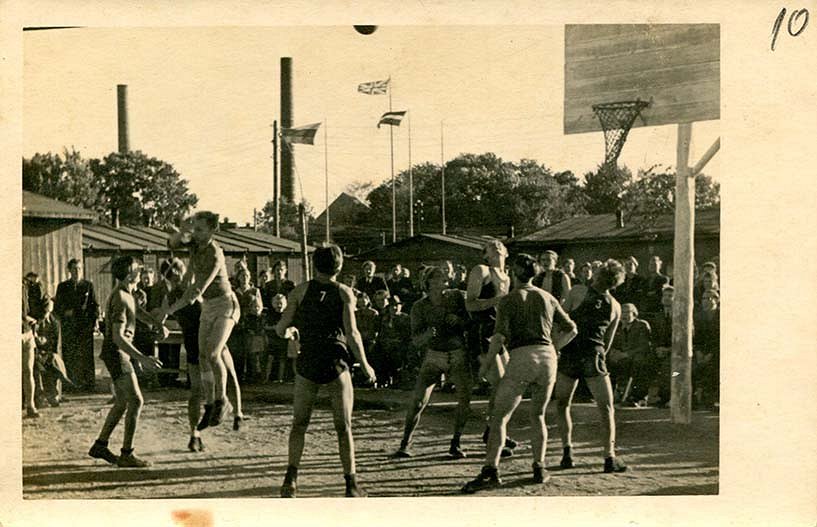

People lived as well as they could. Latvian DPs organized theater troupes, orchestrae and choirs. They played sports games and went on hiking trips. There were schools for Latvian children. Many of those who had gone into exile were young, and their studies had been interrupted by the war.

That's why the educated Baltic peoples joined forces for an even more ambitious step and on January 9, 1946 set up the Baltic University at Hamburg.

Professors from Latvian, Estonian and Lithuanian universities lectured there. Many Balts also studied at other universities, such as the University of the International Refugee Organization (IRO).

Student life was bristling around these institutions. The students wanted to observe the prewar traditions, of which student corporations were an important part. It was unclear whether the prewar corporations would restart operations. That's why in 1947 Latvian students set up four male and three female student corporations.

A life of pervasive doubt

While there were successes in camp government, this did not mean a life of strawberries and cream. Food was scarce, though not to the point of famine. The Allies supplied DPs with 2,000 calories worth of food a day, but it wasn't of great quality and sometimes the ration came short of that. But even if it did not reach 2,000 calories, it was still more than most Germans could have back then. In 1946/1947 when Germany experienced a food crisis, there were cases of DPs exchanging food for other wares or even valuables.

Industrious DPs solved the problem in part by growing their own food and turning their allotments into gardens of berries and root vegetables.

But the psychological toil was the worst. There were no guarantees that the US and the UK wouldn't strike a treaty with the USSR, and some IRO officials thought that many Latvians should be returned to what was now the Soviet Union, because they had collaborated with the Nazis. The doubt was compounded by news of Latvian legionnaires being repatriated from Sweden. The camp management and exiled diplomats took great pains to defend the Latvians' interests.

Many people, especially those in their middle and senior years, were deeply depressed for their lost relatives, homeland and career achievements from before the war. There were also many people who had suffered psychologically and physically. They had little chance of returning to a normal life. There was often abject alcoholism, and many killed themselves.

Younger people would take life at the camps much easier. Many of them later remembered their dipīši years with a tinge of romanticism, remembering their studies at the university, their first trips to the countryside, their first dates and the chance they had of living among Latvians. However almost every single young person dreamed of the chance to leave Germany and embark on a new life in the UK, Australia, Canada, or, in the best possible scenario, in the US.

The end of an era

The well-managed camps ensured that Latvian DPs not only enjoyed a relatively good life but also that they received notice and sympathy from the Allied military personnel and politicians. British, American, Canadian and Australian politicians gradually gained the impression that the Latvians (and the Lithuanians, and the Estonians) were hard-working middle-class protestants, or a "model minority" that would seamlessly integrate wherever they went.

In 1946 the United Kingdom announced the so-called Baltijas gulbēni (Baltic Swans) program that would see the UK admit 5,000 Baltic women to the country to work as hospital nurses.

Even though the quota was not met, from late 1946 throughout 1947 a total of 3,891 women went to the United Kingdom to work. Britain soon announced a similar program for admitting capable young men, and Australia and Canada followed the example soon after.

The program proved that Baltic DPs were not that keen on moving to the UK. Life after the war was quite harsh there, and both Australia and Canada were more attractive in this respect. Most DPs, however, dreamed of going to the US.

Initially, American politicians had reservations over admitting the displaced. However, after pressure from different ethnic groups, particularly Jews, Poles and Lithuanians, as well as religious groups, policies started shifting. On June 25, 1948 president Harry Truman signed the Displaced Persons Act that would see 200,000 DPs admitted. Initially, officials were slow to review the applications, as US institutions were careful not to admit anyone who had collaborated with the Nazis.

Under a definition like this, all the people who served in the Latvian Legion would have been barred from going to the US. However, as relations between the US and the Soviets soured, admission requirements were relaxed.

The US government admitted that the Latvian Legion was fighting the Soviets, not the Western Allies, and therefore former legionnaires were not America's enemies.

As America opened its doors, DPs left their camps en masse. By the end of 1950 most had left to continue their years of exile. Still, to be able to leave for an Anglo-Saxon country, the DPs had to fit strict criteria. They had to be capable of working, preferably young and in good health

But older and disabled people had trouble obtaining permission to leave. As a result, thousands of the least capable people became stuck at the camps. A DP camp in the mid-50s was a disgraceful sight, with the feeble and the weak leading their final days in abject abandonment. Seeing as no one cared about the people remaining in the DP camps, the West German government gradually disbanded the camp network, providing German citizenship to those left behind and closing the Fohrenwald camp, the last to go, in 1957.