More about the cycle of events can be discovered at https://www.gramatai500.lv/ and for more about the Latvian National Library and its constantly changing exhibitions and collections, visit: https://www.lnb.lv/.

The Hartknochs, father-and-son publishers

Who were the Hartknochs, father and son, booksellers and publishers of the Age of Enlightenment in Riga, overshadowed by their illustrious authors yet nevertheless important for the history of Riga and understanding of their age?

Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803), a student of theology in Königsberg and later the great Enlightenment writer and philosopher, is said to have suggested to his friend and fellow student Johann Friedrich Hartknoch (1740–1789) that he should start a bookselling business.

The idea seemed worthwhile to Hartknoch, the son of an organist, born in the East Prussian half-Lithuanian town of Goldap (now in Poland), who successfully turned to the book trade, first as an assistant and the Jelgava representative (1762) of the Königsberg merchant and publisher Johann Jakob Kanter (1728–1786) and later as an independent entrepreneur and merchant.

Hartknoch Snr. soon turned to publishing, which was successfully continued by his son Johann, who, like his father, started working as a bookseller in Riga at the early age of 19 (1787). While his father produced an average of 14 books a year (1780–1789), Hartknoch Jnr. was able to significantly expand his publishing business, publishing as many as 33 books a year (1794). It should be noted, however, that the books published by both Hartknochs were printed in Germany (Leipzig, Berlin) and not in Riga.

Neither Hartknoch the father nor Hartknoch the son had been given permission by the Riga City Council to print their own books (the privilege was granted first to G.K. Froelich, then to J.C.D. Müller), and they were the first publishers in Latvia who did not own their own printing press.

The printing facilities had to be ordered from German printers. The Hartknochs invested their own funds in book publishing, coordinated the work and sold their books both in the Riga shop and at book fairs in Germany. The bookshops run by Hartknoch Snr. in Jelgava (1763–1767) and for the next 20 years in Riga (1765–1789) did well in business, and Hartknoch Snr. is often said to have thanked Herder for his fortune.

Both Hartknochs were successful businessmen who were able to offer their customers a wide range of products: the latest books and periodicals, purchased in book fairs in Germany, and also music publications (sheet music), engravings, maps; the shop even had globes, a herbarium, a microscope, a calculating machine, and even mustard and pearls. According to the 1792 store catalogue printed by Hartknoch Jnr. there were 200 titles on offer, mostly in German and French, but also in English and Spanish.

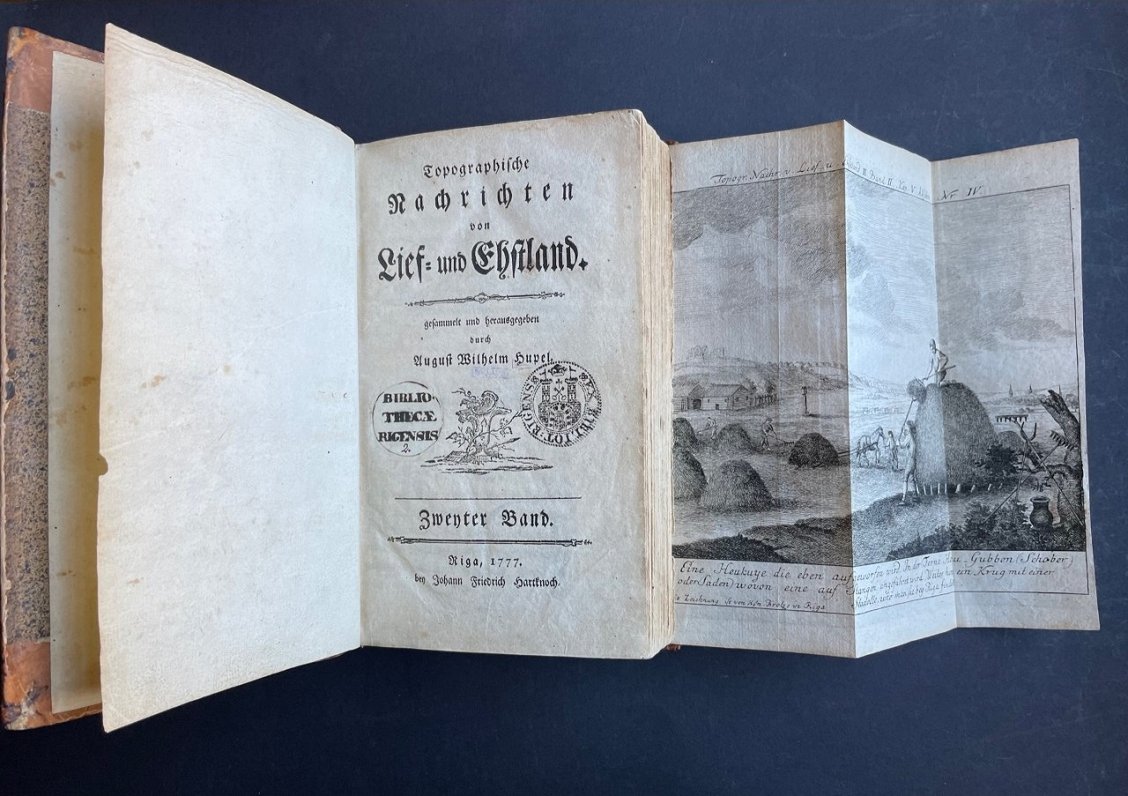

The works of August Wilhelm Hupel, a pastor in Põltsamaa, (Estonia) and member of the Enlightenment, were published by the Hartknochs.

Bookselling by the Hartknochs took many different and flexible forms: books could be bought in person in the shop, they could be ordered in writing, they could be paid for in cash, but they could also be bought on credit or paid for on delivery; books were sent to places as far afield as Livland, Courland and Estonia – at the seller's expense; the customer could also refuse the delivery and Hartknoch would take the books back. In addition, Hartknoch gave a 25% discount to regular customers.

Advertisements in Rigasche Zeitung [The Riga Newspaper] regularly informed readers of new releases. Hartknoch had representatives and commission agents in other cities (Dorpat, Reval/Tallinn, Ösel/Saaremaa, Moscow, St. Petersburg). After his father's death in 1789, his son inherited both his father's business and his extensive contacts in Germany with prominent publishers, printers and booksellers.

The efficient and extensive work of the two Hartknochs in the field of book distribution made the latest literature easily accessible in Livland, and the readership expanded considerably. In addition, both Hartknochs had a remarkable ability to attract and motivate local authors, who now had good opportunities to publish and distribute their works. The books that were published remain important in Livland (Vidzeme) history, local history, topography and cartography, anthropology.

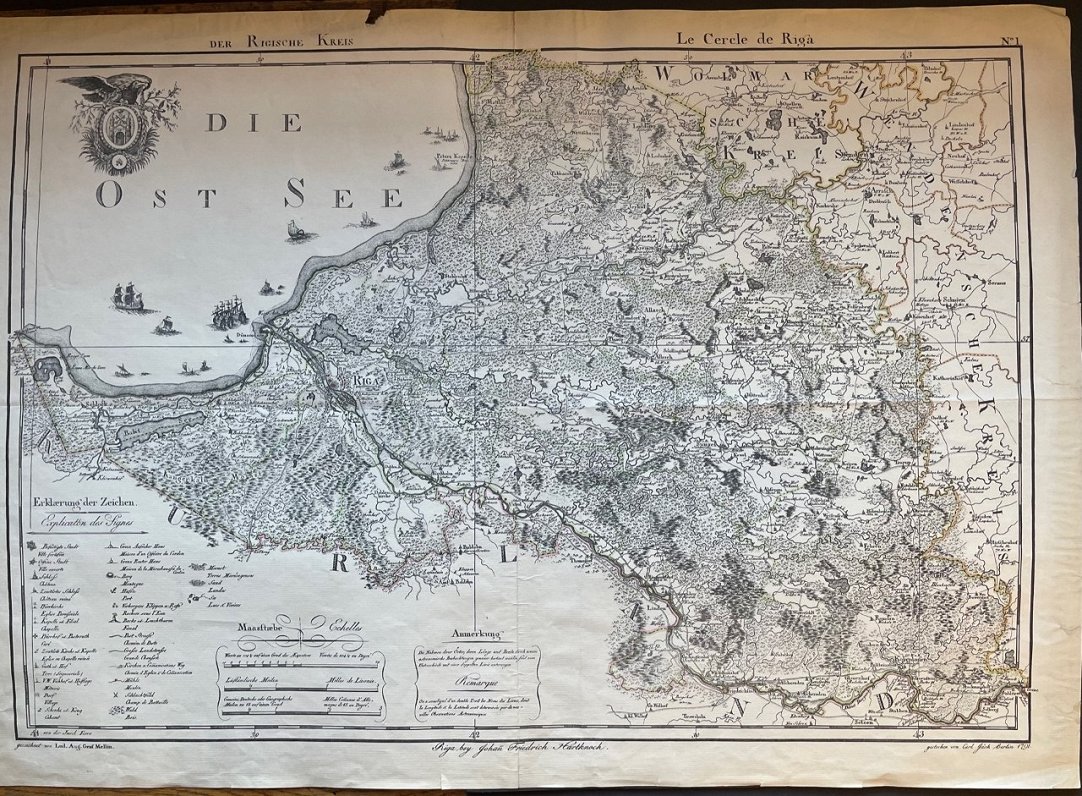

The cartographer Ludwig August Count von Mellin compiled the first accurate atlas of the province of Livland and Estonia (Atlas von Liefland [Atlas of Livland]) between 1791 and 1798, which was published by Hartknoch Jnr. Publishers.

Philanthropy was also important to the Hartknochs: continuing the tradition established by his father, Hartknoch Jnr. donated his books to the Riga City Library annually. The censorship regulations promulgated by Emperor Paul I of Russia (1797), which forbade the sale of any books printed abroad without censorship, proved fatal for the Riga bookshop. The shop suffered a great loss when 34 bundles and boxes of books bought by Hartknoch in Germany were detained in the Riga censorship warehouse for six months without the censors even opening the boxes. In the autumn of 1798, Hartknoch tried to ensure a favourable outcome for himself in St. Petersburg, but in the end, he was arrested by order of Paul I and detained in St Petersburg for several months, which caused alarm and indignation even in German literary circles.

After his release, he had to leave Riga almost by force (March 1798) and at the same time liquidate his publishing house and bookshop. Hartknoch and his family settled in Rudolstadt, in the principality of Schwarzburg (Thuringia), but his publishing house was moved to Leipzig. The 30 years of the Hartknoch company book sales in Riga were over.

Hartknoch Snr.'s previous recommendation enabled the twenty-year-old Herder to secure a position as an assistant teacher (collaborator) and assistant librarian at the Dome School, and later as an assistant pastor in Riga (1764–1769). Hartknoch's shop and house was a place that Herder visited almost daily. In the shop he could browse through the latest books and press publications, and the evenings were spent with his family, where Hartknoch played music, which Herder enjoyed immensely. The talented bookseller played the piano and sang to familiarise his friend with newly acquired sheet music.

Hartknoch published and distributed Herder's first compositions and generously lent his friend money for a trip to France when Herder decided to leave Riga (24.V. 1769). Hartknoch Snr. published the first works by Herder, which were quickly and successfully distributed by his shop and sales network. Herder owes his first literary success to the publishing house and bookshop of Hartknoch Snr. As the German-Baltic philosopher Kurt Stavenhagen aphoristically put it: 'The Herderian style in Herder was raised in Riga' (1925).

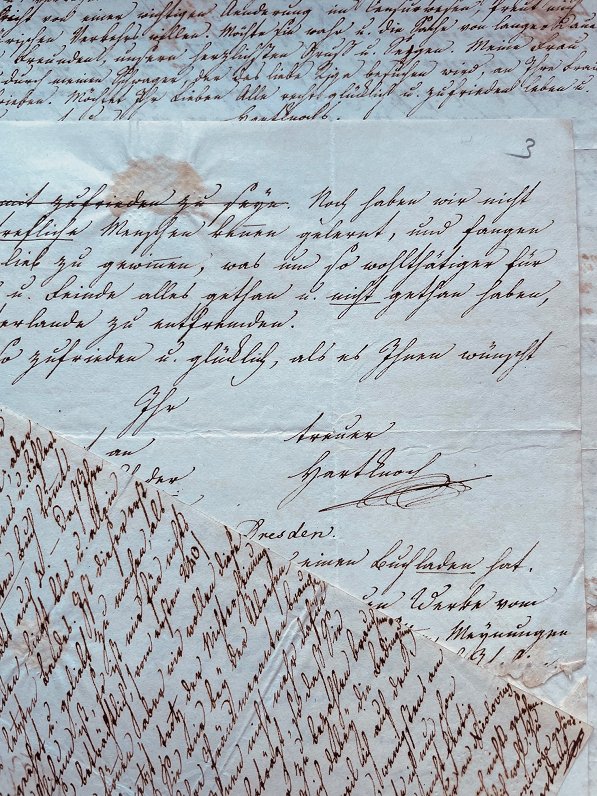

A close friendship and understanding sustained the two – friends since their youth in Königsberg – until the death of Hartknoch Snr. (1789). Cooperation and friendship also united Herder and Hartknoch Jnr. In addition, the Herder and Hartknoch families were also united by family ties. A newly discovered entry in the register of births and baptisms at St. Peter's Church in Riga in 1768 (LVVA, 1427 f., 1.l., p. 203, no. 62) confirms that:

"On 1 July [baptised] Johann, the son of local bookseller Johann Friedrich Hartknoch and his wife Anna Benigna Mehmel.

The godparents: Elder of the Blackheads Johann Zuckerbecker, Elder Bulmerincq, Pastor Herder, Regimental Paramedic Herhold, Doctor Hummius from Jelgava.

Mrs. Zuckerbecker, nee. Kröger, wife of Councillor Janavs, nee. Schröder, Miss Katz from Jelgava.

M: A: Reisner"

The baptismal record by Pastor Martin Andreas Reisner on 1 July 1768 confirms a fact only known in later narratives – that a godfather of the prominent bookseller and publisher Johann Friedrich Hartknoch Jnr. of Riga and Rudolstadt was also Johann Gottfried Herder, pastor of St. Gertrude’s Church and also the Church of Jesus.

Of the eight godparents of Johann, the newborn son of the Riga bookseller Hartknoch, also deserving of mention are the Königsberg-born physician and publicist Karl Ferdinand Hummius (1724–1788), probably also a relative (probably the wife of Hummius and Hartknoch's wife Anna Benigna Mehmel (c.1750–+1771)). The primary godfather was elder of the Riga Blackheads Johann Zuckerbecker (1727–1775), who the child is also named after. Unusual for that time, Hartknoch Jnr. had only one baptismal name, and he is mentioned in his father's will with this name.

Hartknoch Snr., Herder and Zuckerbecker were also united by their membership in the Riga Freemasons' Lodge "Pie Zobena" (Zum Schwerdt – By the Sword). This birth and baptismal certificate could not be found either by the outstanding genealogist August Wilhelm Buchholz (1803–1875) or by Claudia Taszus, researcher of the publisher Hartknoch Snr., during the course of research for her PhD thesis and two-volume monograph (2011). This is most likely because important church records for the family history of Hartknoch Snr. are found in the registers of the Riga Cathedral Church, St Peter's Church and St Jacob's Church in Riga. Therefore, the literature has different versions of the year and date of birth of Hartknoch Jnr.

Tracing the footsteps left by Latvian books for 500 years, it has only just been possible to clarify this for the first time.

It should be noted here that the church register records the date of baptism, not the date of birth, which could have been a few days earlier.

The story of two generations of Riga booksellers and publishers – the Hartknochs – would be bland and abstract if the address of the bookshop were not on the city map. The distance of time leads us to claim that the Hartknoch building in the second half of the 18th century can quite rightly be considered the crossroads of the intellectual and literary life of Riga and the whole Livland region.

It is customary that the authors of the books published by Hartknoch's publishing house have made a name for themselves and gained world fame; the first of these was Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), the great philosopher of the Enlightenment and Hartknoch’s and Herder’s teacher in Königsberg, whose major works were first published with Hartknoch Snr. at the helm.

The title pages of all the books attest to their affiliation: in Riga, published by Johann Friedrich Hartknoch. One does not have to be a philosopher to know and be able to quote one of Kant's most famous and sublime insights in the first Riga edition of Critique of Practical Reason (1788): "Two things fill my mind with new and increasing admiration and awe, the more often and steadily reflection is occupied with them – the starry heaven above me and the moral law within me."

The distinguished authors have left the publishers and their house in the shadows, but the Hartknoch building is important for the history of the city and for understanding of this era. However, it is no longer an urban reality; the location of Hartknochs’ bookshop can only be traced in the memory space of Riga's street network, and efforts to clarify it resemble a detective story, the successful unravelling of which is a tribute to Dr. arch. Ilmārs Dirveiks.

The first Hartknoch bookshop was located in Jauniela for a few years (1765–1767). After Hartknoch had fully moved to Riga, in July 1769 he set up a new and expanded shop in a building on the corner of present-day Smilšu and Mazā Aldaru Streets. Two years later (on 8 July 1771) Hartknoch bought the so-called Gräbner Haus for 2,000 Alberta thalers.

After brief remodelling, the Hartknochs' bookshop was located in this building until Hartknoch Jnr.’s departure from Riga in the spring of 1798. Hartknoch's heirs sold the building in 1834. The antique 18th century building was completely rebuilt (demolished, in actual fact) in 1909, when the Northern Credit Society building was built in the Art Nouveau style on the corner of Smilšu and Mazā Aldaru Streets, designed by the architect Paul Mandelstam.

The streetscape of Smilšu Street was completely and irreversibly transformed by the construction of the Latvian Ministry of Finance, which led to the demolition of several buildings in 1936, including the building on the corner of Smilšu and Mazā Aldaru Streets; Mazā Aldaru Street was also closed at the same time. And so, in the first half of the 20th century, the old Hartknoch building was demolished twice...

The Riga bookshop, so important in the cultural history of the whole of Latvia and also of Europe in the Age of Enlightenment, can be seen only in Riga facade elevations of 1823 – well known to the historians of Riga architecture – which depict a building with a high roof and a classical facade with an oval window (the so-called bull's-eye) in the pediment. The bookshop was located on the ground floor, and there was an annex (warehouse). There is evidence that in 1795 the Hartknoch building was occupied by 14 people, including Hartknoch Jnr. with his wife and two children, his foster mother and her sister, 3 bookshop assistants, one student-helper, 1 servant and 3 maids. Here it is with sadness that I must reproach Johann Christoph Brotze, who at the time had not seen fit to draw either the Hartknoch building or Smilšu Street.

The silhouette of the brightly painted two-storey building still looms in the distance in a couple of turn-of-the-century postcards depicting Smilšu Street. A peculiar tribute to the Hartknochs can be found in the 17th-century building that was erected in 1901 for the 700th anniversary of the Riga Exhibition. In the model of the reconstruction of "Old Riga" (architects Wilhelm Neumann and August Reinberg) one of the houses on Šāļu Street also housed Hartknoch's bookshop. A farewell greeting, still unaware of the imminent changes that will take place with the arrival of the 20th century.

However, for those who would like to enter the world of Riga's booksellers and readers in 1785, Johann Wilhelm Krauze (1757–1828) can help us to look through the door of Hartknoch's shop. Previously a young home tutor in Gaujiena New Manor under Baron Delvig, he was later a master builder and professor of architecture at the University of Tartu. In his later memoirs Wilhelm's Memories, he provided a vivid description of his first meeting with Hartknoch Snr. (who was 45 at the time) and his first impressions of the shop on Smilšu Street:

"December 1785. Not far from [notary] Oxfort lived Hartknoch; the bookshop Wilhelm was looking for was on Smilšu Street. The narrow and crowded office near the front door did not promise much compared to the bookshops of Amsterdam, Hamburg and Leipzig. One salesman – one clerk – and a tall, thin old man with faun-like features – that was all the staff. The old man continued writing – the others did not notice his greeting; nobody offered him anything – nobody showed him anything – nobody prevented him from having access [to the books] – Wilhelm bought the missing textbooks; Horace, Svetony, the odes of Klopstock, Kleist, Gesner, Wendeling’s flute duets, some calendars with Hodowiecki engravings, etc. for himself.

"Now and then the old man looked around, smiling faunally, as if amused at Wilhelm's childish delight – looking especially at some Cipriani – Bartolozzi copper engravings – putting them down again, picking them up, etc., then silent melancholy when the bill was close on 30 thalers, when, as if horrified, he put the engravings down, turned away, never to look at them again.

"Asked his name, status, apartment number – the old man smiled even more – the clerk – put it on the bill or in cash? Wilhelm confessed: he didn't have that much with him – We'll be paid for it for sure, said the old man, – Bookbinders are rare in the countryside, shall we bind them? How? They can be ready in 4 days, etc.– Wilhelm was surprised by such trust and promised: he will bring the money today, but accepted everything else with gratitude, because he is a stranger. He brought the money – the Baron again gave him 50 roubles – (37 ½ thalers), he paid it – 10 per cent was credited to him as a discount – from the fact that he looked at the engravings as if he were in love, it was concluded that he was an art lover, he showed him several engravings, took him to a larger collection further out the back – excellent, but tempting – he fled like Joseph from Potiphar because he gave in to temptation and left a few roubles (. .) as a jacket for two landscapes and two very lovely female figures.

"The old man smiled more and more faunishly, Wilhelm hurried away with his calendars and pictures, as if he had stolen them, to his room, (..) then straight back to the wonderful Hartknoch. A spirit of mutual goodwill and trust developed; he could spend hours here – hours browsing the treasures of science and fine art, buying nothing, often completely alone in the back rooms".

And so, Hartknochs’ books and Hartknochs’ shop have forever etched the name of Riga in the intellectual history of the world.