More about the cycle of events can be discovered at https://www.gramatai500.lv/ and for more about the Latvian National Library and its constantly changing exhibitions and collections, visit: https://www.lnb.lv/.

An 18th century Latvian poet "banished from his job and property". Who was Juris Natanaēls Ramanis?

For a long time, Elkuleju Indriķis was seen to be the first Latvian poet; he was the first one whose poems, or rather songs, were published in printed format. However, long before him, manuscripts of Latvian authors' compositions, including songs, were circulated (e.g. written by members of the Moravian Brethren congregation, or the Herrnhutians). True, they were all anonymous. Then, in 1958 in the Russian State Archives of Ancient Documents in Moscow the historian Marģers Stepermanis found the poetically written complaints of the farmers of Livland (now Vidzeme) to Empress Catherine II, which were compiled by the farmer and weaver Ķikuļa Jēkabs (1740–1777) from Blomu Manor (Blumenhof, near Smiltene). After Stepermanis died, the book historian Aleksejs Apīnis continued his research on the poet of Blomu Manor. In 1982 they resulted in a facsimile edition with extensive commentaries (Ķikuļa Jēkabs. Dziesmas. [Songs] Riga, Liesma, 1982).

In the run-up to 2025, the 500th anniversary of the first book printed in Latvian, Latvian Radio 1 in collaboration with the National Library of Latvia (LNL) broadcast a series "Tracing the Footsteps of Books. The 500th Anniversary of Latvian Books" which explores how the Latvian language and book publishing have developed over five centuries, influencing the dynamics of knowledge, ideas and innovation in Latvia and contributing to us belonging to the European cultural space.

Around the same time, the name of another poet, slightly younger than Ķikuļa Jēkabs, also became more widely known, but this person may also have been connected with the peasant riots in 1777. This was the teacher Juris Natanaēls Ramanis.

There is scant biographical information on him. According to the Latvian school historian Andrejs Vičs, in the 1766 school visitation of the Allaži parish school there is mention of a teacher and teacher's son Juris Ramanis, then 23 years old. Thus, it can be calculated that Juris Ramanis was born around 1743 or more probably in 1742, as the visitation takes place at the beginning of the year.

In 1769 Ramanis is mentioned a second time, already in Krimulda, as an assistant (Substitutus) to the parish teacher, a little later he becomes a full-fledged parish teacher. In 1778, based on the denunciation of pastor Pēlhavs, Ramanis was not only fired from his job as a teacher, but even brought to Riga, accompanied by a peasant guard, for further investigation for an offence "permeated with a spirit of rebellion and causing general indignation".

In his book Peasant Unrest in Livland 1750–1784 the previously mentioned historian Stepermanis mentions that "while searching for the participants of the peasant unrest [in 1777 in Cēsis/Wenden], the teacher Ramanis from Krimulda was dismissed and a rigorous investigation of the case was initiated". No further details of the exact nature of Ramanis' offence have so far been found. However, it is quite likely that this misconduct "branded" Ramanis and influenced his future fate.

The fact that he did not stay in one place for more than a few years is testimony to this, as are his own lines "es dumpis tapis tuksnesī/ es apogs, kur kas izpostī/ tās skaistas māju vietas/ tā dzīvoju es vientulis/ tik grūtās manās lietās" [I rebelled in the desert/ I was a rebel in a desert/ these beautiful places to live / so I live alone / with my difficult situation] and "ak, kaut man būtu bijusi/ kā ceļa vīram tuksnesī/jel kāda mājas vieta" [oh, if only I had/ like a traveller in the desert/ a place that I can call home].

In 1782, there is an entry in the church records of the Madliena (Sissegal) parish that teacher Juris Ramanis from Ozolu Manor (Eichenhof) in Laubere (Laubern) parish was contacted; Ramanis stayed in Laubere until 1785, after which all traces of him disappeared for a long time. Ramanis' name reappears in 1798 in Bērzaune (Bersohn), then in 1799 he was a private tutor for children in Cesvaine (Sesswegen); also in 1801 Georgs Natanaēls Ramanis is mentioned in the church records of this parish as a teacher of the children of the emancipated Latvian farmer Jākobsons, administrator of Dzelzava Manor (Selsau). After this year, there is no more information about Ramanis, where and when he died and where he is buried.

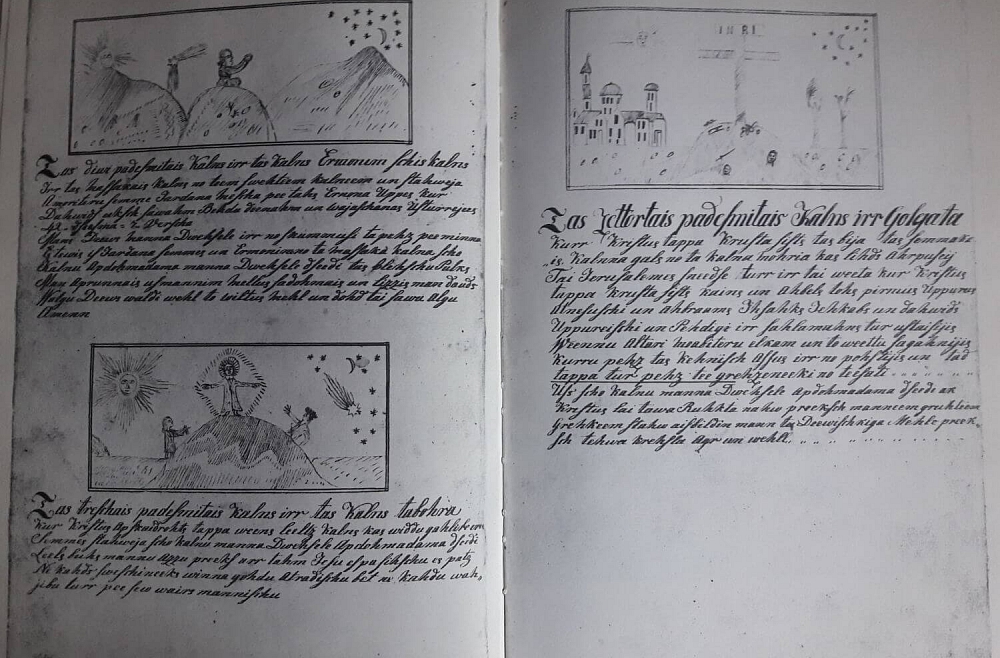

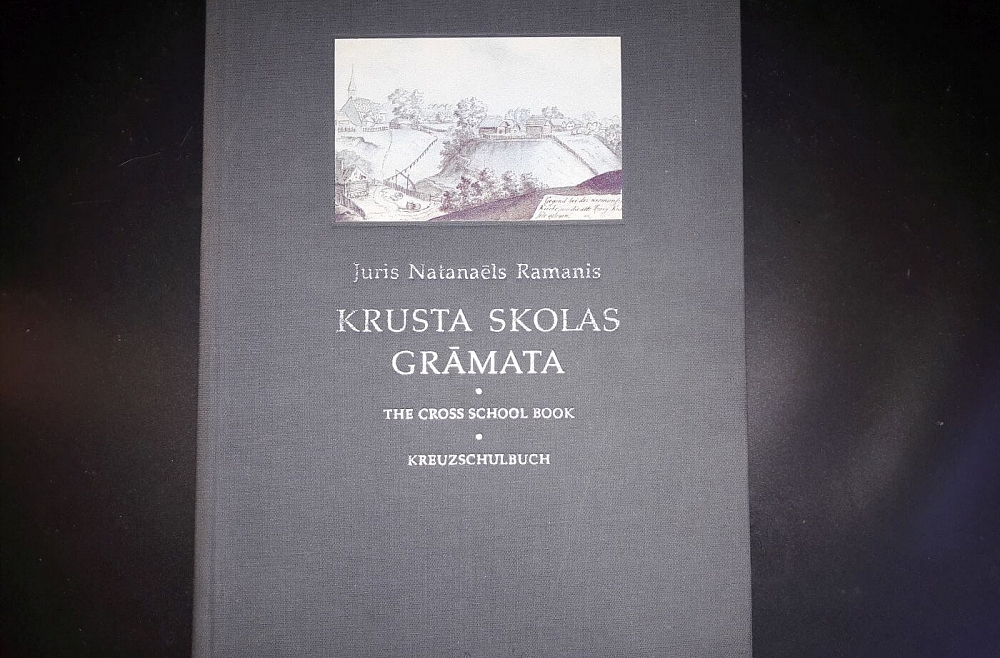

So far, the only known publication by Juris/Georgs Natanaēls Ramanis is the collection Krusta skolas grāmata [The Cross School Book] which has been preserved in 3 copies: in the Manuscripts and Rare Books Department of the Academic Library of Latvia, in the Cēsis Museum of History and Art and in the Latvian National Museum of History. Both of the first two copies are with illustrations (it is important to note that this is the only illustrated work in the history of Latvian manuscript book publishing). The collection contains a total of 18 multi-verse poems, interspersed with prose texts, mostly with biblical themes (Ramanis is very religious).

The importance of Ramanis in the history of Latvian literature is mainly determined by the fact that he makes events in his personal life the central theme of his poetry, as well as social themes that had up till then not been expressed in Latvian poetry with such sharp social criticism.

The main themes of his poetry are: his experiences after losing his position as a teacher ("no god' un mantas es aizdzīts") [banished from my job and property], as well as his attacks on generalised power-mongers, the perpetrators of injustice ("Tu runā taisnību/un saki tādiem vaigā/ ko tādi ēd un dzer, ar ko tie lepni staigā/ ir sviedri, asaras/ ar to tie barojās/ ir ļaužu nopūtas/ un mantas laupītas".) [You speak the truth/and tell such types to their face / what do they eat and drink, what they proudly wear/ are sweat, tears/ what they feed on/ are the sighs of the people/ and things they have plundered].

But often such wielders of power, some of whom "dažs no pīšļiem izrāpjas/ un top par goda kungu" [some of them come out of the dust/ and become honourable gentlement], end their lives sadly: "Bet vētra pār to saceļās/ tāds kuplis ozols nogāžas/ tad guļ tas sūdos, dubļos" [But a storm rises over him/ the large oak falls down/ then it lies in the shit, in the mud].

The prose texts vividly express the author's social addressee – the Latvian people: 'But first of all, God's keeping, may His presence, be and remain for that sad Latvian Zion, for those dear brothers and sisters of the Cross'.

The popularity of Ramanis' poetry and journalism is evidenced by the fact that, in addition to the three copies mentioned above, a larger number of individual fragments were also circulating among the Brethren as late as the 1860s.

In 1993, a memorial to this previously unknown Latvian poet, created by the sculptor Vilnis Titāns was unveiled at the Krimulda Church, and in 1995 the publishing house Zvaigzne ABC published a facsimile of Krusta skolas grāmata [The Cross School Book] with commentary.

As literary scholar Skaidrīte Sirsone points out in her article in this publication, "Ramanis' songs testify to his relatively bright talents as a poet", being "at once a testimony to the life of a particular person and a description of the society of his time through his eyes".