Under lockdown, with the health system in crisis and skyrocketing bills, Latvians are going through a tough time at present. But the current troubles are a piece of cake compared to what earlier generations dealt with.

The Latvian expression “it’s as crazy as 1905” gives an idea of some of those headaches. It is a reference to a year of strikes, protests and violent repression which swept the land as part of a wider revolution in the Russian Empire.

The turbulence of that era spread far beyond the shores of the Baltic Sea. After the revolution, some Latvians fleeing brutal reprisals by the czarist authorities found a safe haven in Britain. But instead of leading a quiet life there, they turned to crime to finance their cause.

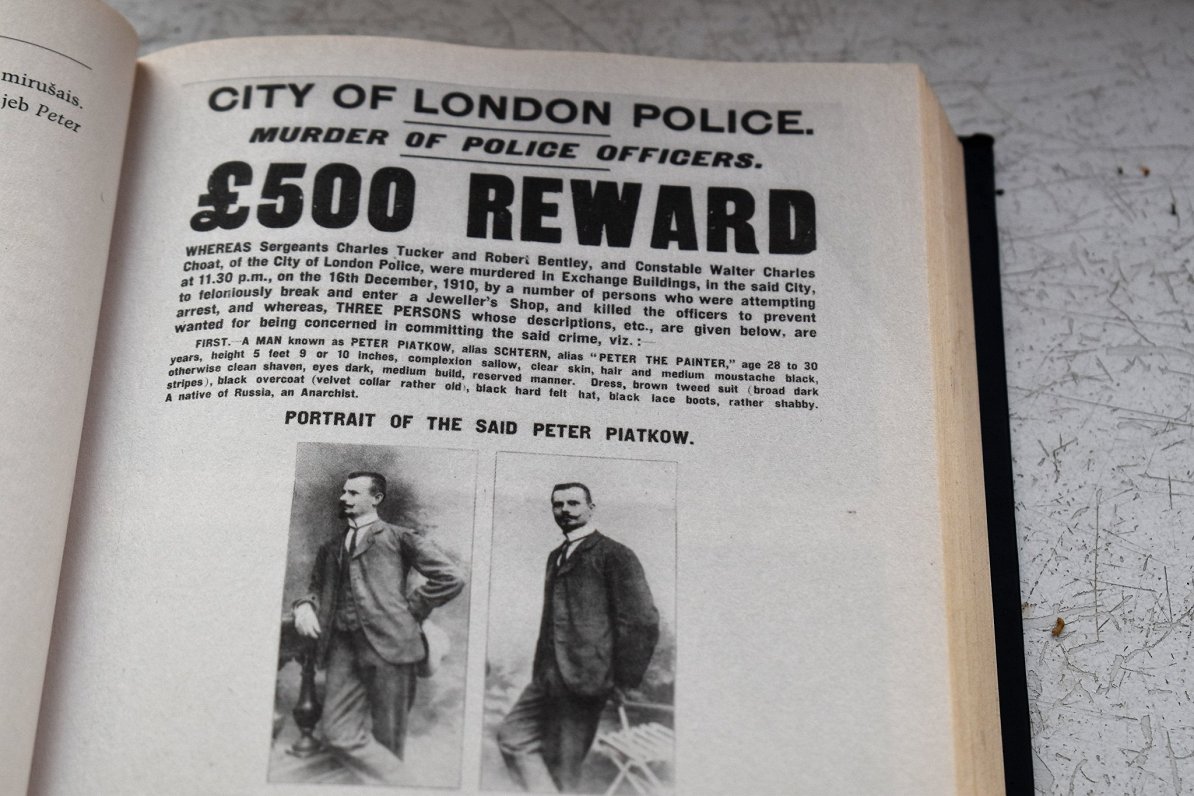

On 16 December 1910, police interrupted a burglary at a jewellery store in London’s Houndsditch neighbourhood. The robbers shot three unarmed bobbies dead and left two wounded, unleashing a panic about foreign terrorists in the UK.

A few weeks later, some suspects were cornered in a house in Sidney Street in London’s East End. The then Home Secretary, Winston Churchill, regarded the outlaws as so dangerous that he ordered in army units and broke tradition by giving the police firearms.

After a shootout lasting several hours, one of the first news stories ever captured on film, the house caught fire. While the remains of two men were found in the ruins, it was believed their leader somehow escaped the inferno.

Dubbed “Peter the Painter,” this mysterious figure became a legend. Books and movies have been dedicated to him, and for decades there has been speculation about his true identity.

Up in arms

In the late 1980s, as glasnost eased tensions between east and west, British historian Philip Ruff came to Riga to try and solve the riddle. A self-confessed “retired anarchist” who was involved with urban guerrilla movements in the 1970s, he clearly has a soft spot for troublemakers.

“All the English writers about the Siege of Sidney Street agreed they were Latvians,” he says. “But no one had ever thought to go to Latvia to make enquiries, or at least to consult Latvian sources.”

One of Philip’s first stops was a place few people ever went to voluntarily - Riga’s KGB headquarters. He explains this move with a classic one-liner: “I interviewed them – usually it’s the other way round.” But this was only the beginning of years of research.

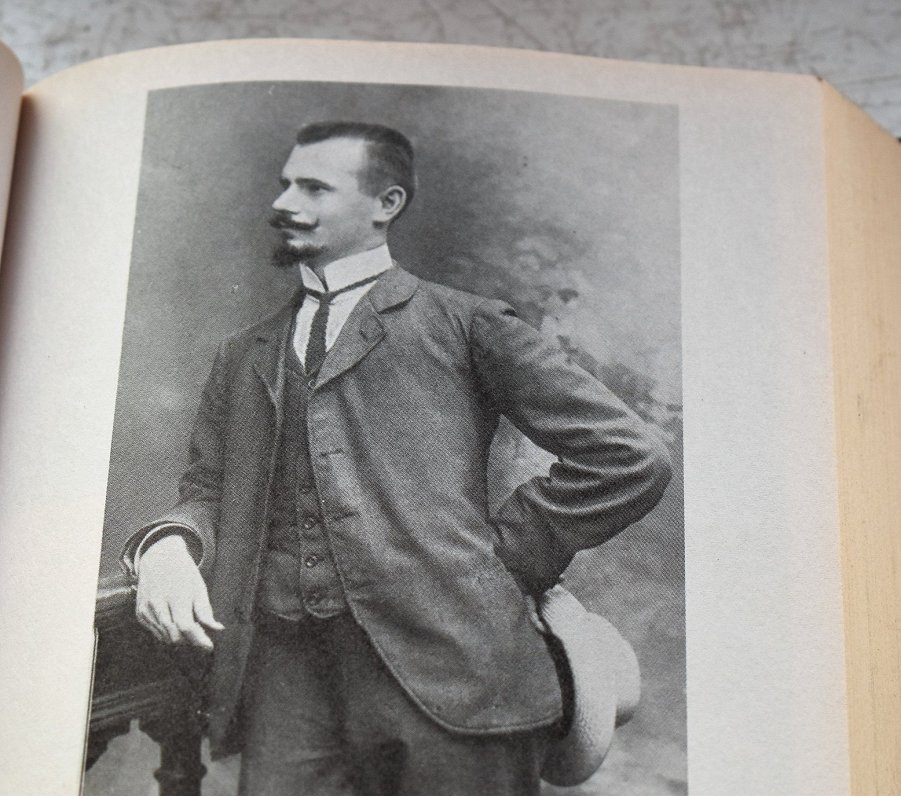

Philip’s breakthrough came when he found an original photograph in the Latvian War Museum of a man who was the spitting image of famous “wanted” posters for Peter the Painter. And on the back of the photo was a name – Jānis Žāklis.

Žāklis’ story was so fascinating that Philip eventually published a book about him titled “A Towering Flame: The Life and Times of the Elusive Latvian Anarchist Peter the Painter,” which has been released in English and Latvian. It is the story of an extraordinary character in a dramatic time and place.

The 1905 Revolution began in Latvia on 13 January 1905, when Cossacks attacked a peaceful demonstration by the Daugava River in Riga, killing dozens of people. Subsequently, the Latvian Social Democratic Workers Party, which despite being illegal was one of the largest political organisations in the Russian Empire, established an armed unit for defence against state violence. Jānis Žāklis was appointed its leader.

Žāklis, who grew up on a farm in Kurzeme, had an exciting 1905 to say the least. He led attacks on Riga’s Central Prison and Secret Police Headquarters to free jailed comrades. He and his men prevented attempts by far-right groups from Russia to carry out a pogrom in Rīga’s Jewish quarter. And he made trips to the countryside to aid rebels in the provinces.

By late 1905, Latvian revolutionaries had been so successful that a situation of dual power existed in the country. But it was not to last, as in 1906 the Czar sent in thousands of troops to brutally crush the uprising. Žāklis and many others had to flee their homeland.

Most of the revolutionaries of 1905 who remained at home decided to work within the limited democracy the Czar permitted after the fuss died down. But Žāklis and other exiles felt that the armed struggle had to continue, and they began to identify themselves as anarchists. It is known that Žāklis led a clandestine existence in Finland, the USA and Britain, but whether he was really in Sidney Street on that fateful day in 1911 will probably never be known.

But Philip believes Žāklis eventually made a personal great escape. Avoiding execution or jail like most of his comrades, he emigrated to Australia, where he lived out his life in obscurity.

Villain or hero?

Philip’s ties with Latvia have deepened over the years. He eventually married his research translator Irēna. He is currently writing a historical novel based on events in Latvia during the Second World War and revolutionary groups in Germany in the 1970s.

And he wants Latvians to rediscover their own past, shrouded in the fog of Soviet-era propaganda. After the 1917 revolution, the Bolsheviks liquidated many anarchists, and claimed a role for themselves in movements they actually played little part in.

In Philip’s view, Latvians have rarely been as united as they were in 1905, battling aristocratic German landowners and czarist autocracy. And the emerging Latvian middle class was deeply committed to the cause, with former firebrands becoming respectable citizens in the independent republic between the wars.

“Almost every Latvian family has an ancestor who was involved in the events of 1905,” says Philip. “But they weren’t the stereotypical peasants with straw coming out of their ears led by heroic Russian Bolsheviks – they were also educated people. Žāklis spoke six languages and his father was a relatively prosperous man.”

Another common view dismissed by Philip is that the revolutionaries were criminals.

”The real terrorists were Russian state actors who ordered and carried out massacres,” he says. “Whatever violence was perpetrated by the fighting groups was armed resistance too this state terror.”

Many of the events of 1905 described in Philip’s book, including bomb blasts, gunfights and mass demonstrations, took place in the Riga district of Grīziņkalns. This working class neighbourhood is the setting for the Latvian novel and film “Vārnu ielas republika” about children growing up during the revolution, as well as the recent Latvian movie “1906” about the last desperate days of the uprising. In the picture for this story, Philip poses in front of a monument in Grīziņkalns dedicated to the bricklayers, chimneysweeps and other tradesmen who built the area.

You can also find out more about Jānis Žāklis, and perhaps even contribute to his story yourself, at an exhibition currently running in Talsi (once we are out of lockdown, at least).