The second stop (after the PMLP website) for anyone considering applying for Latvian citizenship should be the excellent six-part series written by Ksenija Koļesņikova and Anna Shtefan, who outlined their own naturalization processes on LSM a couple of years ago.

I found myself reading their accounts repeatedly until they gained the status almost of a definitive reference work, giving valuable information about what might be expected to happen and in what order, while also providing reassurance that it is quite normal for oddities or anomalies to be encountered along the way.

The cause of my own inertia was an inherent aversion to paperwork. I file things away with all the care and attention to detail of a dog rolling in the grass, and when too much paperwork accumulates I simply throw it out on the basis of its weight and dimensions rather than its importance. It is likely I have thrown out several winning lottery tickets in this manner.

Such was my lackadaisical attitude to paperwork that it was only when I started thinking about the paperwork I would need for my Latvian citizenship application that I realized I would first have to get my British paperwork up to date. My passport and driving license were both in urgent need of renewal, and it cost quite a lot to get new ones delivered from the other side of Europe simply for the purpose of superseding them with Latvian equivalents.

So as soon as I got my new British driving license I traded it in for a Latvian one. This involved having an afternoon of medical examinations, which included, somewhat ironically, having to ride an exercise bike for twenty minutes while chatting to a very pleasant doctor about her family's summer holiday plans.

Later, at the Road Transport Safety Directorate (CSDD) office the license switch took no more than 15 minutes and was very efficiently done. Most of that time was taken up with the clerk asking repeatedly: "So you are sure you want to swap your 10-year UK license for a 5-year Latvian license?"

"I think it's probably the safest option," I said, thinking of the contradictory advice on such matters occasionally wafting over like a bad smell from London to UK citizens in Europe. Walking out of the CSDD office with my new license was nice, like a little starter course in anticipation of what would hopefully be the slap-up citizenship meal to follow.

We may like to talk about the digital society but we remain at the mercy of paperwork, stamps and certificates. I constantly thanked my good luck a few years earlier when I went to renew my residence permit. The first such permit I had in Latvia was a pathetic piece of white paper. The week before I went to get it renewed at the main PMLP office in Rīga I happened to write a news story about the introduction of new eID cards.

When the PMLP clerk produced another piece of flimsy paper which looked like he might almost have run it off on a Xerox machine, I demanded the new eID card instead and provided a lengthy explanation of what they were and why they had been introduced, based entirely on the story I had copied from a press release issued by his own office a week earlier. Presumably I sounded like some sort of expert because he quickly produced a card, without which I would have had a lot more trouble in the subsequent years.

The hardest part of the whole paper chase was proving I wasn't a dangerous criminal. Only when I first tried to submit my citizenship application did I learn of this missing piece of the jigsaw. I needed something from the UK authorities on an official piece of paper and with a translation attesting to the fact that I was not The Pink Panther. No-one seemed sure exactly what this certificate should be, other than it should definitely be official and have a stamp and a signature on it.

A friend suggested a background or 'DBS' check might be the answer. These are commonly used by UK employers to check a potential employee's criminal record. I found an agency in Scotland that could act as an intermediary for overseas applicants. Inevitably, this required both a hefty fee and a lot more paperwork.

Indeed, I had to supply more paperwork for the application for a certificate I would then use as part of the paperwork for an application for naturalization than I had to supply for the citizenship application itself, if that makes sense. Paperwork, like bureaucracy, bacteria and Bond films, tends to generate more of itself with increasing speed but diminishing attractiveness. Add in the generous amount of paperwork I had already supplied for the renewed driving license and passport and I was starting to think myself lucky to live in a country with large forests and hence ample supplies of wood pulp.

One of the things required by the DBS check was a sworn statement by a responsible person that I was indeed who I claimed to be. This responsible person had to come from a restricted and picturesque list of professions including lawyer, doctor (my thoughts returned briefly to the exercise bike), high court judge, sea captain, member of parliament...

Member of parliament? Thanks to my work as a journalist I knew several members of parliament! It struck me that it would be quite amusing to have a member of parliament on my application.

I will not embarrass the Saeima deputy who helped me out by naming them, but their assistance was very generously given and I like to think that in some Glasgow office a few days later, a junior employee opened the mail and was suitably impressed to see that I had a member of parliament on my application for a criminal record check.

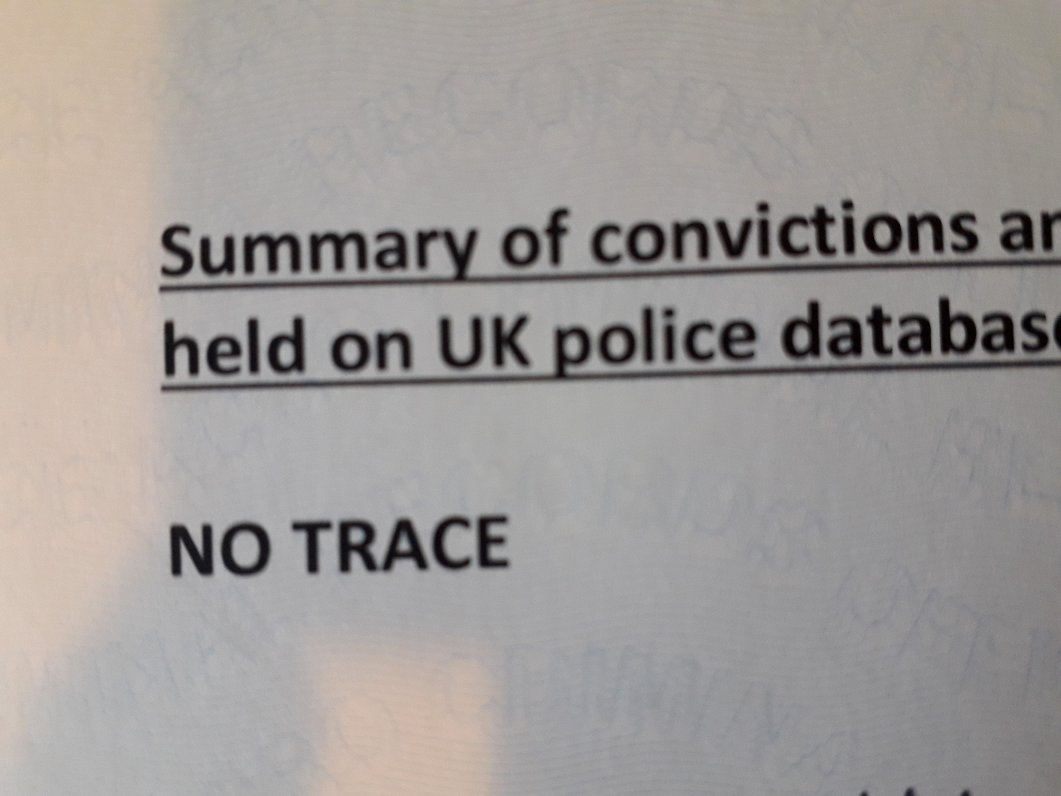

A week later a certificate arrived confirming my lack of a criminal record, despite being a known associate of a member of parliament. I took it to the PMLP office who accepted it. Then rejected it.

It turned out that I should have had an ACRO check of the police computers to confirm I had no criminal record, not a DBS check of the police computers to confirm I had no criminal record! A silly mistake.

I filled out more forms, I supplied the same proofs of identity, address and other details, the same statement from the same member of parliament saying I was me, I sent some more money and waited. This time I ordered two copies of the certificate, just for fun.

The certificate arrived a week later. It summed up my exciting criminal career in the rather anti-climactic words: "NO TRACE". I took the new certificate to the PMLP and kept the other one as a souvenir of this paperwork-heavy period of my life. The certificate was satisfactory. My application to start the naturalization process was accepted.

"Where would you like to do the tests, Rīga or Valmiera?" asked the PMLP clerk in Cēsis, "They happen more often in Rīga."

"Valmiera," I said.

"The next one there is in three weeks. Shall I put you down for that? And you'll need these," she said, bringing out a series of booklets, each explaining a different aspect of the naturalization tests and giving sample questions and answers.

The naturalization process was no longer an abstract concept somewhere in the future. I was in it. I swallowed hard and started to perspire.

"There's also this," she continued, bringing out a thick book on the history and constitution of Latvia, "It's not compulsory to read it, but it is helpful. If you want it, I'm afraid it isn't for free, unlike the rest of these booklets."

"I'll buy it!" I said.

After two years of prevarication, suddenly three weeks did not seem long enough.