Experts point out that both national investments in science and the overall understanding of the contribution of different sectors to the development of the country are essential.

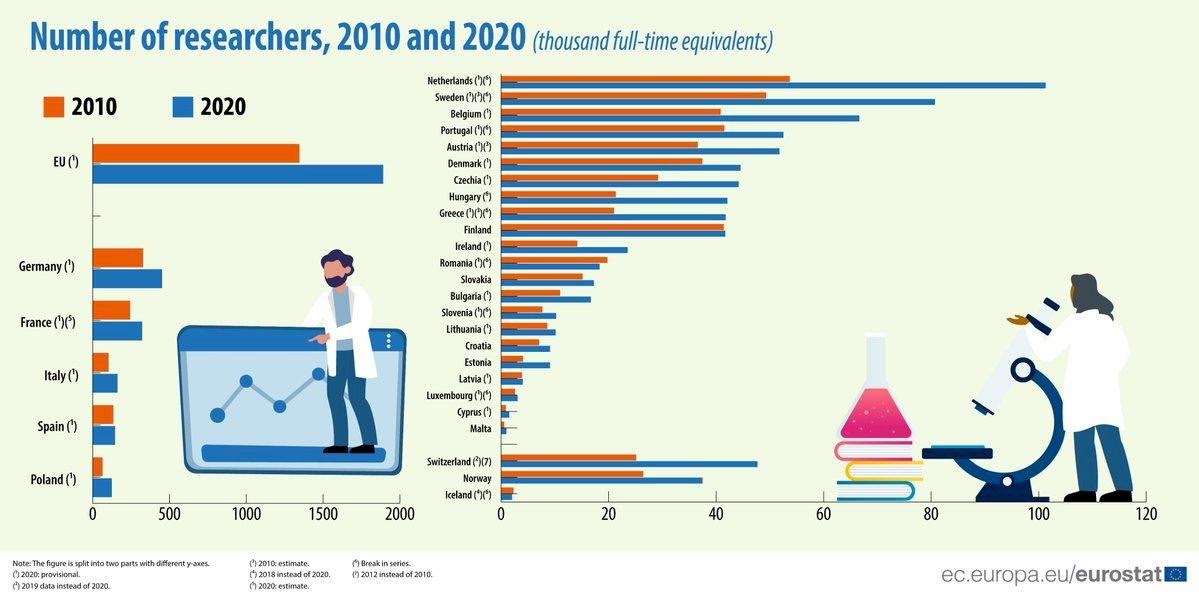

Scientific progress has been made in most EU Member States over the past decade. Between 2010 and 2020, the number of researchers in the EU increased by more than a third (41%). In 2020, 1.9 million researchers worked in the Member States, an increase of 546,000 compared to 2010.

Number of researchers in the European Union. Photo: Eurostat

In Latvia, the total number of scientists has not increased over the last decade, and the number of research workers is slightly over 4,000. Some researchers are not employed exclusively in science or work part-time, so in order to compare the data in the EU as a whole and in Latvia, the statistics employed in science are measured by listing the workload or their full-time equivalent (FTE).

"Of course, official statistics from the EU and Latvia show that the FTE of researchers is critically low compared to the EU average. Unfortunately, there is no observable trend of this increase, although in recent years the increase in the FTE of researchers has been the primary objective of science policy,” said Ina Druviete, former Minister for Education and Science.

Looking at the causes of the low number of researchers, Rīga Stradiņš University (RSU) Science Prorector Agrita Kiopa notes two.

“First of all, in any government until the Krišjānis Kariņš government, politicians had no understanding that knowledge and technology were driving economic growth, so no investment in science was actually made.”

Kiopa added that the situation was further aggravated by the very simplified interpretation of what public-private investments mean and how they are related.

“Secondly, in the wake of the 2008 crisis, austerity and cuts in the public sector led to a dramatic downward cut in public investment. As a result, many scientists emigrated or retrained,” Kiopa said.

Meanwhile, other European countries, including Estonia and Lithuania, have continued to increase investment as far as possible. The contribution is also reflected in the number of researchers. While around 4,000 researchers are working in Latvia, around 5,000 are in neighbouring Estonia which has a smaller population, and around 10,000 in Lithuania.

Average load on researchers in EU countries (2019). Source: Eurostat

“In this respect, the solution is only one – a substantial increase in science funding,” said Professor Druviete. “As long as it is not there, let us only look for more fair principles for distributing small money, which will in no way contribute to the increase in the number of researchers and the need for scientific development.”

THE RSU Prorector Kiopa looks at the situation in a similar way, pointing out that the number of scientists is directly dependent on investment and correlates with their contribution to both science and the public and private sectors.

“We as a country invest little and our industrial structure is one that has few companies funding research. Accordingly, there are few jobs and opportunities for talents."

Latvia's research and development system is excessively dependent on the availability of the EU Structural Funds (39% of research and development funding in 2014-2018 was provided from foreign sources, mainly EU structural funds) which is also indicated in the IZM policy planning documents.

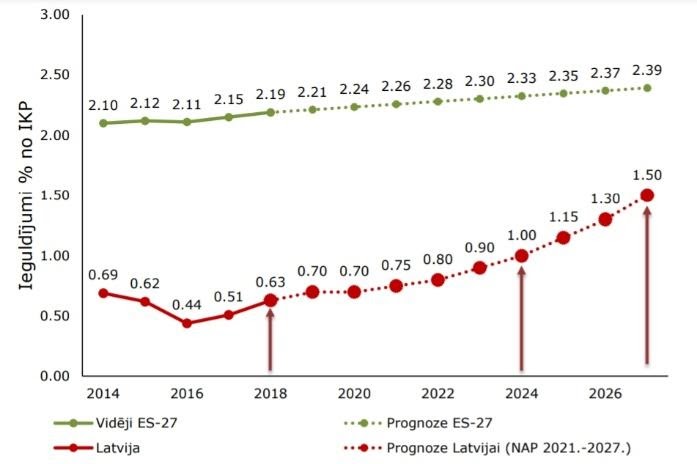

The current government plan, however, provides for a gradual increase in investment in research from national resources. Policy-making plans currently include the target of increasing the percentage of R & D from GDP to 1% by 2024 and 1.5% of GDP by 2027. The planned outcome of such a policy is developed research excellence, capacity and international cooperation.

Investments in science (as a percentage of gross domestic product). Source: Education and Science Ministry's Science, Technological Development and Innovation Guidelines for 2021-2027

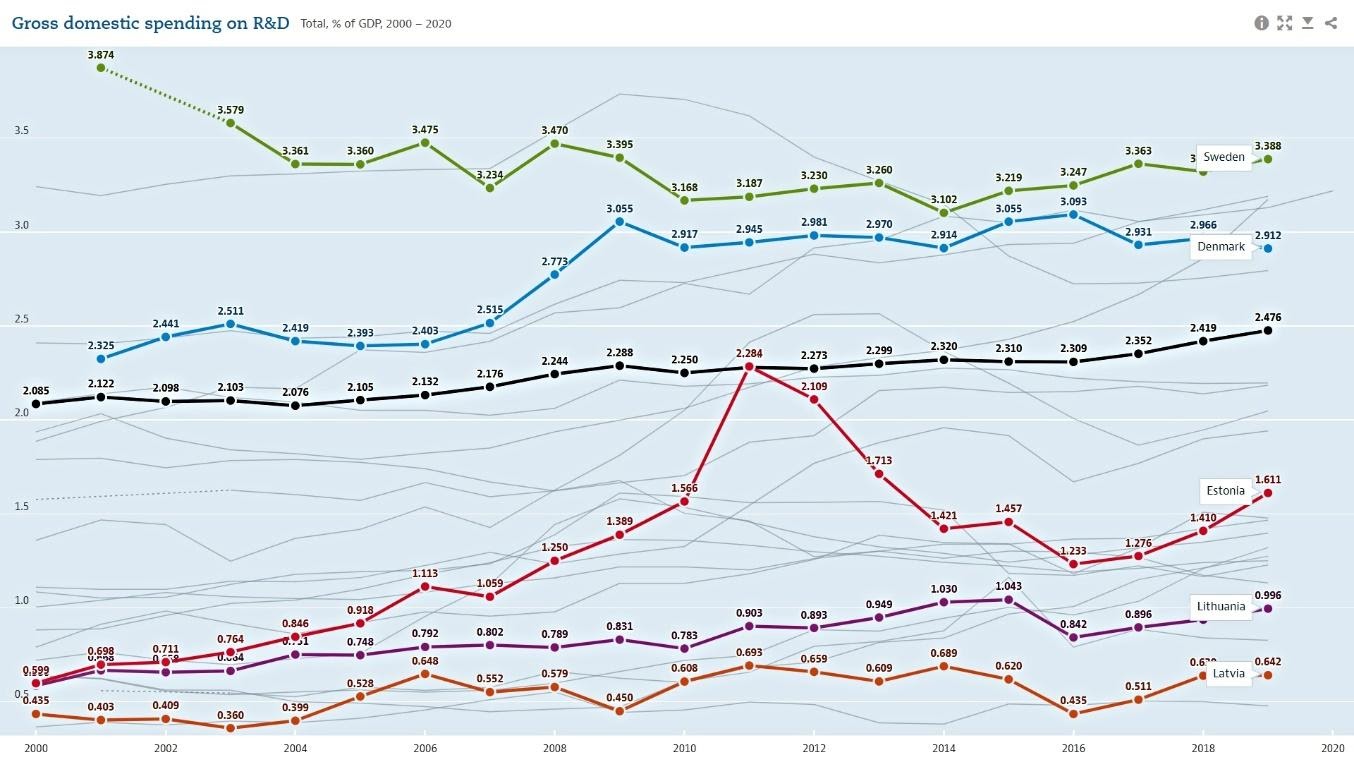

Latvia's domestic spending on research and development over the past two decades still lag significantly not only from Lithuania and Estonia but also from almost all other member states of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

Investment in R & D (% of gross domestic product). Photo: OECD

In looking at possible financing solutions, Professor Aigars Jirgensons, deputy director of the Latvian Institute for Organic Synthesis, points out that in countries with a large increase in scientists, the indicator is mainly positively influenced by the corresponding growth in the business sector.

“The involvement of scientists in the business sector is determined by the number of science-intensive companies, including start-ups, and the desire of large companies to expand R & D.”

The professor acknowledged that developing the environment of science-intensive companies and promoting the creation of innovative products is a difficult process. "This is affected by both State aid programmes and private investment opportunities. An important factor is also the number of prepared PhDs who become R & D workers or innovative business makers,“ said Jirgensons.

In Latvia, the involvement of scientists in the business sector has not changed significantly over the last decade, but in future, support is promised. According to the professor, it aims to increase investment in research and innovation from public budget funds, the EU Structural Funds and the Recovery and Resilience Facility.

“In order for these investments to achieve the desired objective, a very sound and coordinated plan of measures is needed, based on dialogue between policymakers, producers and scientists,” stresses Jirgensons.

IN the opinion of the RSU Prorector Agita Kiopa, the course of this government should now be continued, with targeted investment in areas of public interest. “Then it will also be possible to obtain a larger share of EU science funding and to create preconditions for the development of more technologically intensive companies here with us.”

It is important that investment in science comes with challenges in different sectors. “For example, in the field of health, the Ministry of Health is funding research on key health issues – Covid–19, oncology, mental health, sexual and reproductive health and so on,” Kiopa said.

In the Ministry of Culture, this would be additional financing for matters of communication and public value, while in the Ministry of Defence, security issues and technology.

“In this way, there would be jobs in science in the form of a public order, which would then be shown in statistics accordingly. But more importantly, make us smarter and stronger,” said Kiopa.

The outlook is expected to change, as the latest ZM criteria for allocating base and performance funding foresee abandoning the FTE criterion in the future, taking into account, instead, the amount of remuneration actually paid to scientific staff.

“We are looking forward to amendments to Cabinet regulations that would give a detailed picture of the change. At present, it seems likely that more equitable principles for the distribution of funds could be introduced. This is not directly linked to pay increases,” added Professor Druviete.