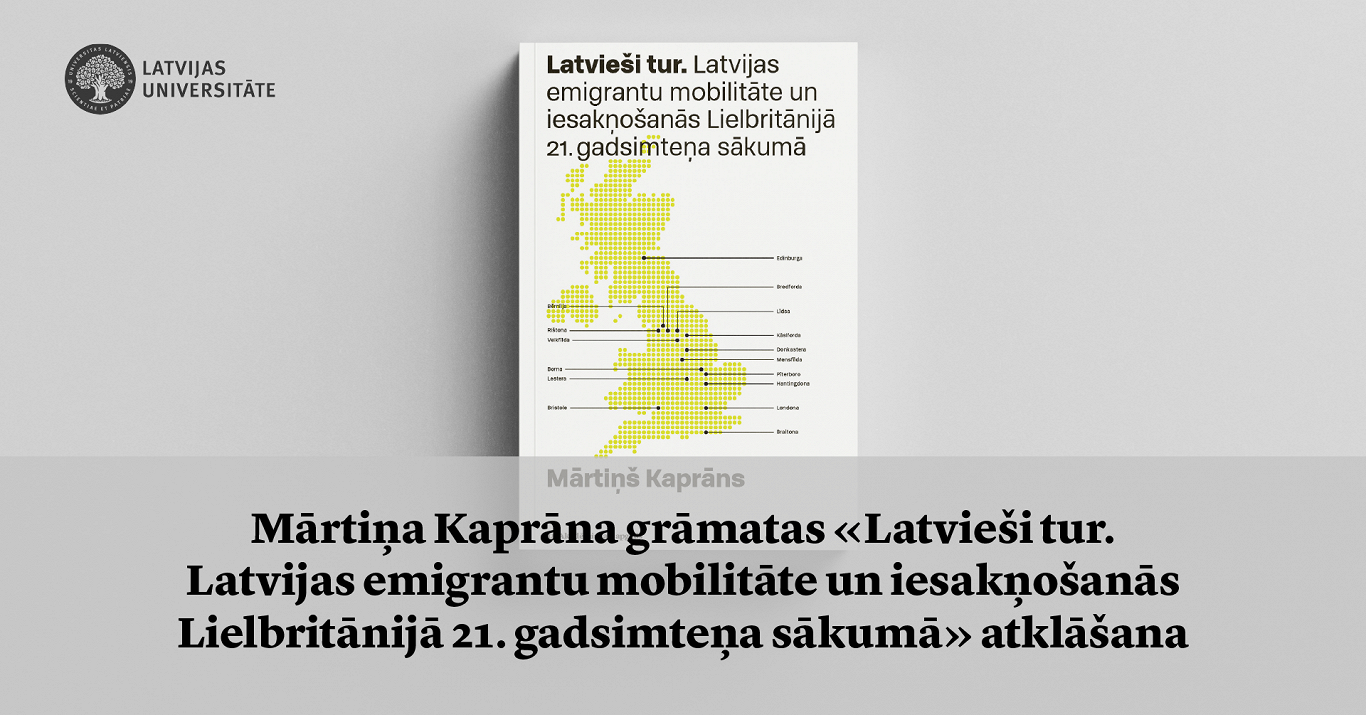

His findings have been turned into a book titled "Latvians there. The mobility and rootedness of Latvian emigrants in Great Britain at the beginning of the 21st century" ("Latvieši tur. Latvijas emigrantu mobilitāte un iesakņošanās Lielbritānijā 21. gadu simteņa sākumā"). At present it is only available in Latvian.

Mārtiņš Kaprāns talked to LSM about how and why he chose this as a research subject, the results he obtained, and how his findings might be of use to future diaspora policymakers.

LSM: You started this project way back in 2014. How did it come about?

Mārtiņš Kaprāns: 2014 was a time when we were still coping with the consequences of the great recession in Latvia and there was still a huge post-recession crisis in emigration that we could observe – not as sizeable as it was in 2011-2, but still noticeable. I come from the countryside and I had a personal attachment to this issue. I felt that many of my contemporaries who I knew growing up had actually left and migrated to the UK, so there was not only a scholarly interest in this.

Combining these two things together I decided when I had finished my PhD. that I needed a new direction for my research and this somehow addressed me very directly, and I thought it was a very hot topic. Initially I focused more on topics that dealt more with how they maintained their ties with Latvia but then Brexit happened in 2016 and I decided this was a natural experiment – not a lab experiment but a natural experiment – in how Brexit was going to shape the trajectories of Latvians in particular but also generally of all these migrants who have come to the UK.

LSM: With immigration being so widely discussed in the UK itself, you almost had two parallel narratives.

Mārtiņš Kaprāns: Yes, there was what was happening in the UK including of course all the anti-immigrant sentiments in society increasing and at the same time all this moral panic in Latvia exacerbated by politicians who were capitalizing on this issue – that everyone is leaving and no-one's going to stay here.

In the UK there was a short-term increase not only in hate speech but also hate crimes. There are statistics that confirm this very compellingly. So these different processes gave me very interesting settings for my research, but when I started the second [part of the] project I decided that I want to focus more on the 'typical' Latvian emigrant, if I may use such a categorization. That is, a migrant who is not working in a high-skill sector but doing a lower-skilled job and particularly not living in London.

I went there, I traveled and visited them at home, had dinner together, was privileged to see their private space – which was actually not so easy as many of them were quite suspicious towards me. These were not friends of mine, I appeared out of nowhere for them, approaching them through Facebook or other indirect contacts and I had to make a lot of effort to convince them to trust me.

LSM: It comes across very strongly in the research that you are not talking with a 'classic' or 'romanticized' diaspora that is expected to participate in certain activities and act as mini-ambassadors for Latvia. What was it they were hoping to find in the UK – one phrase you use is "a liveable life". Was it something other than just money?

Mārtiņš Kaprāns: To some extent yes, though of course money is still very important. Most of them left Latvia for socio-economic reasons, but 'socio' and 'economic' are not always overlapping. I remember one interviewer told me 'In England there is different air' by which he meant that he couldn't breathe in Latvia, there is too much social pressure on how to live your life.

The economic reason is very important. When they come to the UK and understand that they can earn a salary which is four or five times bigger than they received in Latvia then that's one very defining moment – that I can afford a decent house, I can afford holidays and travel, so these are very banal but important factors of a liveable life for people.

The majority of Latvians still have some property here [in Latvia]. Some of them actually left due to mortgage problems. They have relatives, they have property so they are still involved in paying remittances. That connection has not disappeared but the very fact that they have understood this bottom line they have built for a liveable life in th UK – that is not something they feel they could obtain in Latvia.

LSM: Why did they choose to go to the UK in particular?

Mārtiņš Kaprāns: For a long time the UK had the most liberal immigration regime for workforce, unlike Germany and some other countries. Also salary-wise it was more competitive in comparison with Ireland for example, which was initially the most-desired target country.

But these two factors, that the UK was so open and the British labor market was so flexible, provided many opportunities in this low skill – and low-paid by British standards – sectors. You could come and know that on the second day you could get a job. That helped to overcome any potential insecurities. It was less risky than other countries.

After Brexit, we can observe that there is more competition [for jobs] from Germany, Norway, Sweden and some other countries, influenced by the decreasing value of the pound.

LSM: Reading the research, I was constantly asking myself: 'To what extent is this migrant experience and to what extent is it experience of being part of the British working class?' It seems the Latvian migrants had a strong belief in British meritocracy which maybe was rather idealistic. Do they feel that they are part of a working class or are they set apart as part of a migrant class, or a bit of both?

Mārtiņš Kaprāns: That's a very important question. On the one hand they of course are separated. The first thing that should be taken into account is that the absolute majority of these Latvian migrants are encircled by what you would call the British working class. These are the streets they live on. They interact, they create the image of British society, so this British working class kind of mediates the image of British society in general and in fact [Latvians] call them "Īsti Angļi" ["Real English"], genuine English people.

On the one hand that's the source for them that can provide information about British culture, but on the other hand it's very much a constrained and framed way of seeing British society. Particularly younger Latvians learn British working class language, accent. That kind of helps them to become a part of society with British working class people as a bridge, but then they also learn many other things including anti-immigrant and racist attitudes from these people.

But if we speak about this class structure it's very interesting. I tried to provoke them during my interviews to think in class categories and they are not very eager to think that they somehow represent a more deprived economic class. They do not think in these hierarchical categories about themselves and to some extent, it's quite helpful not to think that way. It opens some gates that could be closed due to prejudices or thinking 'That's not for me, that's for another class'.

I quote Orwell in my book from 'The Road To Wigan Pier' where he argues that this class pride that every class in British society shares – I think you wouldn't be able to find it among migrants.

LSM: Many of your interviewees clearly believed that if they worked hard – and obtained langage skills – they could advance, socially speaking.

Martiņš Kaprāns: There is still a glass ceiling. It was interesting that the most articulate and the most explicit about their social position were the high-skilled Latvians working in high-skill sectors. They actually were the most outspoken about the glass ceilings created due to class differences in British society. One told me that if in Latvia almost anyone could become Prime Minister, then in the UK a similar thing is not very likely.

LSM: Looking at some of the discussion of your research here in Latvia, journalists tend to stress that we in Latvia should not 'look down' on people who have gone to the UK, while at the same time the Latvians who have made lives in the UK face the possibility of 'looking down' on people who stayed behind in Latvia, which suggests we have a strange battle of identities taking place over who are the "Real Latvians". What is the identity of Latvians living in the UK, where do they feel they belong and where will they belong in the future?

Martiņš Kaprāns: I think the first generation will definitely maintain this duality. It's inevitable. More intriguing is what's going to happen with the second generation. Linguistic assimilation is happening so quickly that, linguistically speaking, they are already part and parcel of British society, but when it comes to social horizons that's still a very open question.

Some of them try to jump on the social elevator and try to get somewhere higher through the education system. In this way maybe belief in a meritocratic system is still a guiding principle of how they see themselves. But many are not so successful and they are repeating the patterns they see from their parents – live in a rented house, have jobs in maybe the medium-skilled sector. They are largely teenagers so maybe their identity is still very open, nationally speaking. It's still unclear what is going to happen with them, whether they can become full members of British society with this migrant background and constant reminders that they are migrants. This may produce feelings of isolation.

To some extent we can draw parallels with Russian-speakers here in Latvia. For similar reasons, if someone is all the time pointing at them and saying 'You do not qualify fully as a member of this society' it reproduces this kind of self-isolation.

LSM: What would be your recommendations for policymakers as regards future diaspora policy?

Martiņš Kaprāns: The [current] policy is often guided by this romanticized image of the Latvian diaspora: well-educated, socially active, having ties with both the host society and Latvia, but I think there are certain limits. It's not so much a recommendation, but just be more realistic with regard to expectations. It's not so easy to address the sensibilities of those typical migrants living in the UK who are maybe not so much interested in maintaining diasporic ties while living there.

On the other hand I understand – if I were a politician I would do the same. That's the name of the game. Politicians should address the diaspora in a romanticized way, to an extent. It's very appealing to both local voters and those who have left Latvia because if politicians start to speak in language like me, saying we should be ready for the majority not coming back and the next generation will most likely not consider themselves to be Latvians, that's not a very good strategy for politicians!

My advice would be more directed at Latvian society in general. We have to maybe change our thinking about this romanticized, idealized idea of migrants who are political and economic subjects living in other countries and not so much representatives of Latvian culture who are really eager to maintain this culture.

But I don't think we should necessarily be pessimistic. It's very important that we see a tiny but very active group, which does not exceed 10 percent of all the Latvians living in the UK, who are very active in the diaspora. They are active in sports, cultural, and philanthropic activities. They form the core of this new diaspora and this is the group that should be strengthened and targeted. That's a group we have to work with, I think.