Nearly 25 years after Latvia regained its independence, the prison system still functions according to the traditions it inherited from the Soviet Union. Latvian prisons are considered more like torture camps, not correctional facilities, writes Inga Sprinģe, Re:Baltica’s Latvian team-member.

Latvia has more than double the amount of prisoners than the average in the European Union and at least five times more than Norway, which is considered by some to be the example of how prison systems should be run. Latvia and Estonia most commonly sentence criminals to 5 - 10 year sentences. The average conviction length in the EU is 1 to 3 years.

But the long sentences don’t magically transform the convicts into better people, rather the opposite. 51% of the people released after serving a full sentence commit repeat felonies within two years’ time after release. These people are usually young men who couldn't reintegrate back into the society.

The public believes the strong punishments create a safer society, yet instead it actually creates more criminals.

Three castes

“Society doesn't want to imagine that prison isn't the end of the problem. The most important thing is who will be the person coming out of that prison? Society wouldn't feel safer if they realized that the person that comes back has spent years in inhumane conditions and learned even more methods to commit crimes,” said Ilona Supre (44), the Interior Ministry’s chief of prison administration. “Usually it starts with petty theft like a mobile phone or jar of jam in the nearby summer cottage, but next time they are back in prison for a gang robbery, then assault and battery and it can even end in murder.”

There are three castes in the Latvian prison hierarchy. Blatnije (from Russian - favor in exchange for another favor ) are the VIP caste. Mužiki (from Russian - implies that someone is “a real man”) are the average thugs. And then there's kreisie (from Latvian, word for “left”), the bottom feeders. The average thugs are subservient to the VIP caste or else they will be booted down to the bottom feeder level. The bottom feeders have no choice but to serve the thugs who only use them for their own purposes. The VIP prisoners don't ever speak to or use the same utilities as bottom feeders.

Criminology expert and former chief of prison administration Vitolds Zahars says that the prison hierarchy is “a structure created by the prisoners themselves based on a sense of justice based on a set of values only understood by the prisoners themselves”.

Pedophiles and rapists are automatically deemed bottom feeders and they are kept in separate cells for their own safety. But prisoners can be booted down to the bottom feeder tier for even menial reasons like gambling debts or stealing food from other inmates.

Capitalism has brought some changes to the structure, though. In the prison of Jēkabpils an inmate recently entered the prison as a VIP by paying for the installation of new windows in the prison. A lack of money can also be a reason to be deemed a bottom feeder.

Over the past few years there have been several reported complaints about the quality of life on the lowest level. “Bottom feeders can't be in the same place as the upper castes. Can't use the same toilets, use the gym or use the computers,” writes one of the inmates.

In 2012 Latvia’s Supreme Court stated that it is the state's responsibility to prevent violence in prisons as well as the informal hierarchy, because it is one of the main reasons for violence. The court cited European Committee for the Prevention of Torture (CPT) reports which emphasize that “the possibility of being a victim of battery, sexual assault, extortion and other forms of abuse is everyday life for many prisoners.

The complaints prisoners write to Latvia’s state Ombudsman usually are general and do not describe the attacks in enough detail for prosecution. The inmates either do not believe that the investigations will be fair or are afraid of revenge.

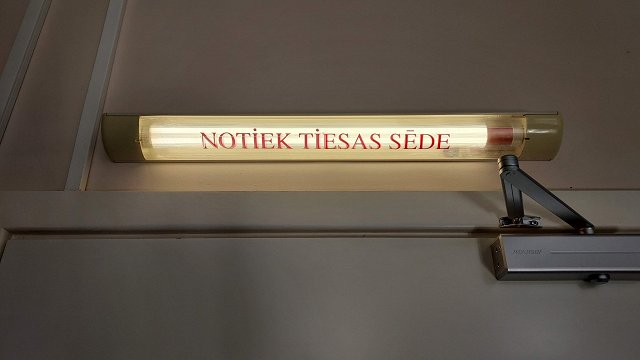

Latvian prisons hold between 5000-6000 prisoners. Every year, on average 16 criminal investigations are opened (Estonia has about 80 cases a year and its prison population is smaller). About 90% of the cases never reach the court as the evidence during investigations is deemed inconclusive.

Usually the finding is that prisoners hurt themselves by accident. Over the last seven years only two sexual assault cases have made it to court.

Investigations are done by prisons’ administrations. Both the inmates and the CPT do not believe that they are properly conducted and often resemble a cover-up. The CTP has suggested independent inquiries as a solution, but the government’s promises have never been followed by action.

The refusal to create an independent investigation unit for prison crime in Latvia almost led to an international scandal in 2013. The CPT was so angered by the neglected promises that it was considering the release of a special statement about the state of prisons in Latvia. The CPT has issued such condemnations to only three countries before: Russia, Turkey and Greece.

Latva is discussing a plan to trust the investigation of prison crimes to a special unit within the Ministry of Interior which deals with the crimes within law enforcement agencies.

Another indicator of the problems within Latvian prisons is the high suicide rate. 2012 was the worst year, when 8 inmates committed suicide (in 2013 - 3 people). Almost half of those inmates were still waiting for their trials to begin.

The administration has a huge influence on the prison environment. The former chief, veteran traffic policeman, Visvaldis Puķīte was the embodiment of society's prejudices. One of the first things Puķīte did when he began work in 2007 was to purge the Prison Administration’s spokesman because "the people do not need to know what happens in the jails”, remembers the prison’s former PR chief, currently Saeima MP, Kārlis Seržants.

In 2007 the European Court of Human Rights ordered the Latvian government to pay €7000 to a prisoner who complained about inhumane treatment.

"That man would smell and look worse outside of prison than in," Puķīte said. Suicide rates? "Free will, that's all. I don't think it's our fault that he didn't await the final hearing and judgment. He punished himself out of a moral principle" Puķīte told Latvian daily newspaper Diena.

In the last decade the European Court of Human Rights has forced the Latvian government to pay €67 000 for inhumane treatment of prisoners.

New blood, high hopes

A new administration and a new prison are two things that could change Latvia's prison subculture in the next few years. In 2013, Ilona Spure (44) became the new Chief Administrator of prisons. She has an MA degree in pedagogy and nearly 20 years of work experience in the prison system, the last being responsibility for reintegrating the prisoners back into society.

Spure’s priority is to finish a building the extension of the prison in Olaine by 2016. The new section would be capable of rehabilitating up to 200 addicts (80% of prisoners are addicted to drugs or drink, but the prisons offer only short term rehab programs).

The new section will cost around €8.2 million. 15% is to be provided by Latvia and the rest funded by Norway.

“It will be a testing grounds where we'll explore new approaches. This would include adjusting the attitudes of older employees of the system in order to make a change in the Soviet system,” said Spure.

The new prison in Liepaja will be about the same size as the current largest, the Central Prison, which contains 1200 inmates. Academic literature refers to these types of prison as “Titanics” due to the amount of resources required for safety.

“There's nothing humane about the new prisons as they are too big. Maximum security forces the prisoners to feel like criminals constantly, which means they can't return to society as normal human beings,” says Estonian criminologist Anna Markina.

Spure says that the new prison in Liepāja will be managed like it consisted of several smaller prisons with their own individual personnel. Cells will be either for 1 or 2 persons.

Multiple prisoners will only gather in class or during events. Estonia, which succeeded in changing the prison subculture in this way, is advising Latvia on this project.

Spure hopes to also hire only motivated employees in the prisons of Olaine and Liepāja, but may encounter roadblocks in the labour market. A prison guard’s salary in Latvia is €670 a month before tax. They work in shifts and get additional pay for the night shifts. No one is stampeding toward vacancies in the prison sector. The Central Prison has almost 90 unfilled positions.

The psychologists and social workers in prisons work daily and get €570 a month before taxes. Their workload is insane.

Government regulations require 1 psychologist for every 75 inmates. In reality, it is 1 for every 255 inmates.

If all the reforms are successful, the prison system will become less expensive to run and more effective in the long term. Recent years have seen a tendency to replace imprisonment with probation for less significant crimes. This also saves money, as one prisoner costs the state €18 a day while someone on probation only costs €1.50 a day.

There's also a lower rate of repeat offenses. 16% of people on probation commit repeat felonies while 50% of people in prison will also engage in criminal activity again.

In 2015, Latvia will introduce electronic tagging of prisoners. Prisoners on parole will have electronic tracking devices attached to their legs to monitor their movement. The use of tracking devices could cut expenses down to €10 a day per prisoner. Estonia’s experience shows that the biggest advantage of the tagging is the ability of prisoner to return to their family, find a job and contribute to society.