A well-protected testimony to its time

Nowadays, the Latvian anthem is stored at the Museum of the History of Riga and Navigation away from visitors' eyes. An old heavy door leads to a small room with low lightning and a number of closed shelves – this is the storage room of the fund dedicated to Latvian music history, the Song and Dance Festivals, and the nation's first composers. Museum employee Antija Erdmane-Hermane carefully removes an envelope from a box and, having donned silk gloves, slowly produces a gray sheet of paper.

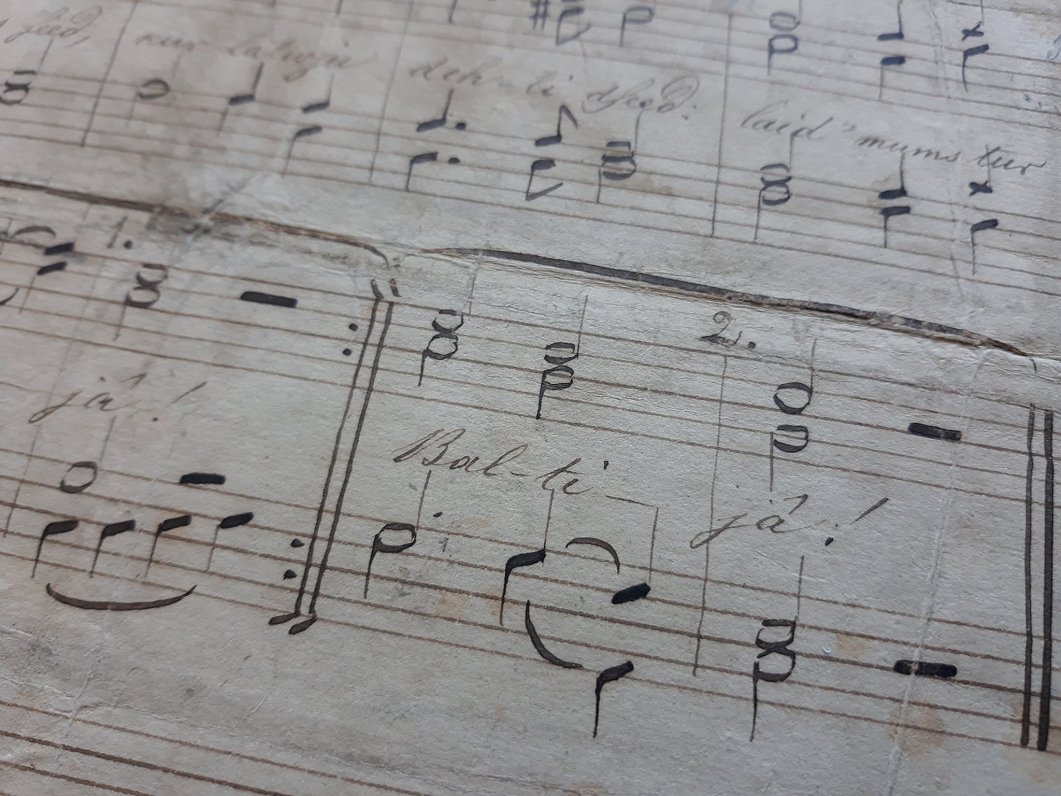

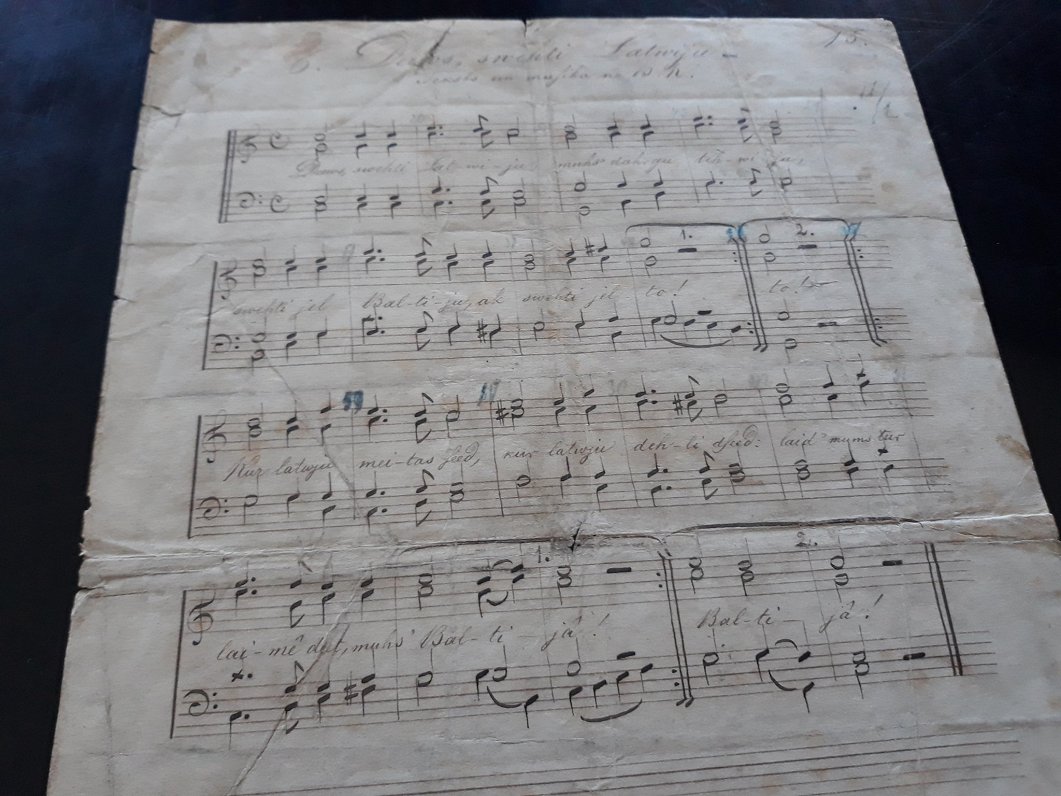

"As you can see, the original is in a rather poor condition. It was that way when it arrived, with brown stains and handwriting in brown ink. [..] It was likely stored with the sheet music facing down, with books or other objects leaving impressions on paper. It's likely there was humidity as well, leaving its traces on the paper," said Erdmane-Hermane.

The manuscript of the Latvian anthem by Kārlis Baumanis is a minuscule, calligraphic sheet score. 148 years old (it was written in 1872), the manuscript antedates its official designation as the national anthem by almost 50 years.

The original is very seldom removed from its location, it is never scanned and kept at a particular temperature and humidity.

The manuscript arrived to the Rīga History Museum in 1937 from the former State History Museum, but its prior tradition is unknown. The Zemgales Balss newspaper reported in 1936, however, that Baumanis gave the original copy of the anthem to Jānis Pētersons, a friend who studied Russian from the composer. The manuscript had almost perished in a fire in 1920 in Moscow where Pētersons lived. In a weird twist, a firefighter had actually looted Pētersons' apartment, the newspaper reports, but hadn't thought the tiny scrap of paper to be of any value.

Modern sounds

Below is a rendition by renowned pianist Vestards Šimkus, transposed and played at a quicker pace.

Trial by fire

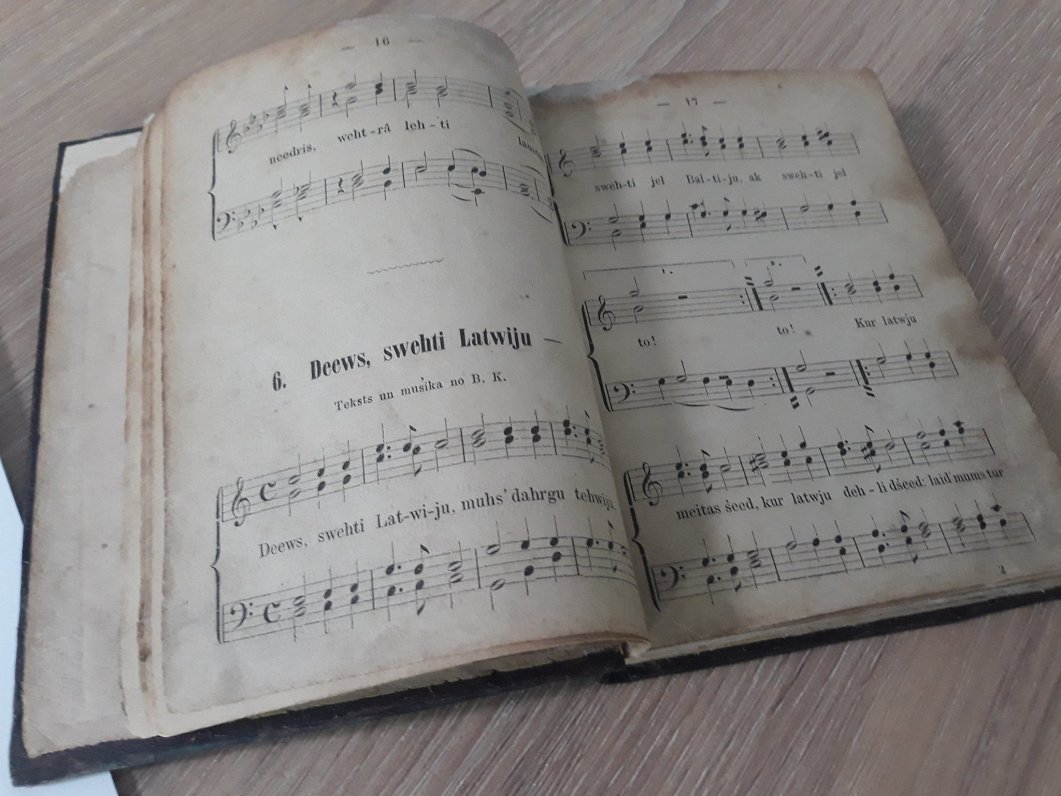

The song and lyrics were first published in the 1874 collection Austra. That same year, Baumanis also published the song book Līgo, which likewise included the anthem. These books are highly sought-after these days. Dzintars Gilba, a researcher at the Literature and Music Museum, showed a book at the museum collection, a small binding with black covers. This is one of the few copies of the Līgo song book that have survived to this day, because all the printed copies were confiscated in 1874 and burned at the bank of River Daugava.

"They burned it not because it includes God Bless Latvia but because Baumaņu Kārlis had a sharp tongue and had quite a few enemies," Gilba says. At that time Baumanis was very political, a member of the St. Petersburg Latvian Society, the Society for Latvian Letters and the Baltijas vēstnesis newspaper. He published pieces criticizing German landowners and the clergy.

In 1877 Baumanis put together another collection, Vītols, in three volumes. The original is stored at the National Library of Latvia. The censor's signature testifies that the content was to be okayed, but Vītols was never released. Often the song was published with different lyrics as 'Latvija' was replaced with 'Baltija' or the word for fatherland. In 1880, when the song was first performed at a public concert, it was performed as God Bless the Baltic.

A non-expurgated version was first performed publicly in 1895 at the Song Festival held in Jelgava. It was a massive event, with a wooden stage constructed to hold 30,000 people, while the organizer – the great composer Jānis Čakste used diplomatic wit to secure the go-ahead to have the song performed as written originally.

A state symbol protected by law

According to Diāna Nipāne, the song which was to become the Latvian anthem started living a life of its own. "In the 1905 [revolution] when the Latvians raised their head, what did they sing? They sang God Bless Latvia. What did they sing during the Christmas Battles in World War I? They sang God Bless Latvia. It was perceived as an anthem of the people. When the Republic of Latvia was proclaimed on November 18, 1918 the participants sang the song thrice," she says.

Jānis Kudiņš agrees: "No-one even asked questions about an anthem. There was no official anthem. But somehow everyone realized that out of many historical and patriotic songs they had to sing exactly this song. The people's prayer, God Bless Latvia."

Kudiņš likewise maps out the uncertainties concerning official recognition. Any discussions prior to that have been lost to time, but on June 7, 1920 it was granted official status by Interior Minister Alfrēds Bergs of the Latvian Provisional Government. Interestingly enough, Kudiņš notes that the official communication only refers to the anthem as the "people's solemn prayer". It was only codified on September 25, 1928.

Overshadowed by the Soviets

The Latgalian Song Festival, held at Daugavpils' Stropi open-air stage, was the last time the song would be performed officially before Soviet occupation. It was June 16, 1940. "The feeling of premonition was in a way surreal. No one knew anything. Ulmanis' authoritarian regime was in place. Sadly he did a lot of harm as he didn't let the public in on the imminent danger, because the press was under complete control and censorship. Many things that happened in the world were unknown to the public. But people had a hunch, as we can gather from the eyewitnesses' memories. Something was about to happen, something was not right," says Kudiņš.

At the event, it was performed three times. The event ended close to midnight. The next morning saw the arrival of the Soviet army.

The anthem lost its official status July 19, 1945 when Anatols Liepiņš' Song About Soviet Latvia was made the anthem. Dzintars Gilba notes that it was banned in Latvia but was still sung in the free world, performed without censorship in the US and Germany, across DP camps, in the UK and Australia – wherever there were Latvians, it was sung as the national anthem.