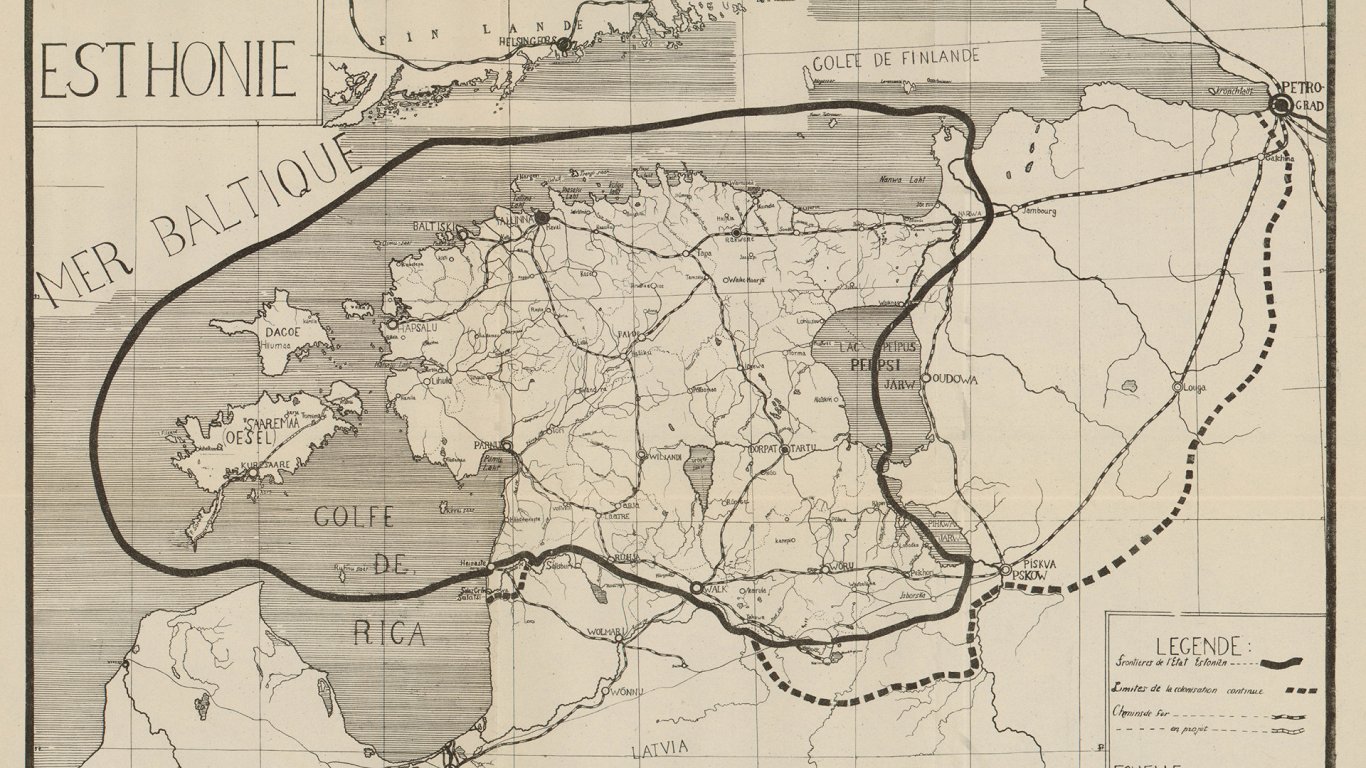

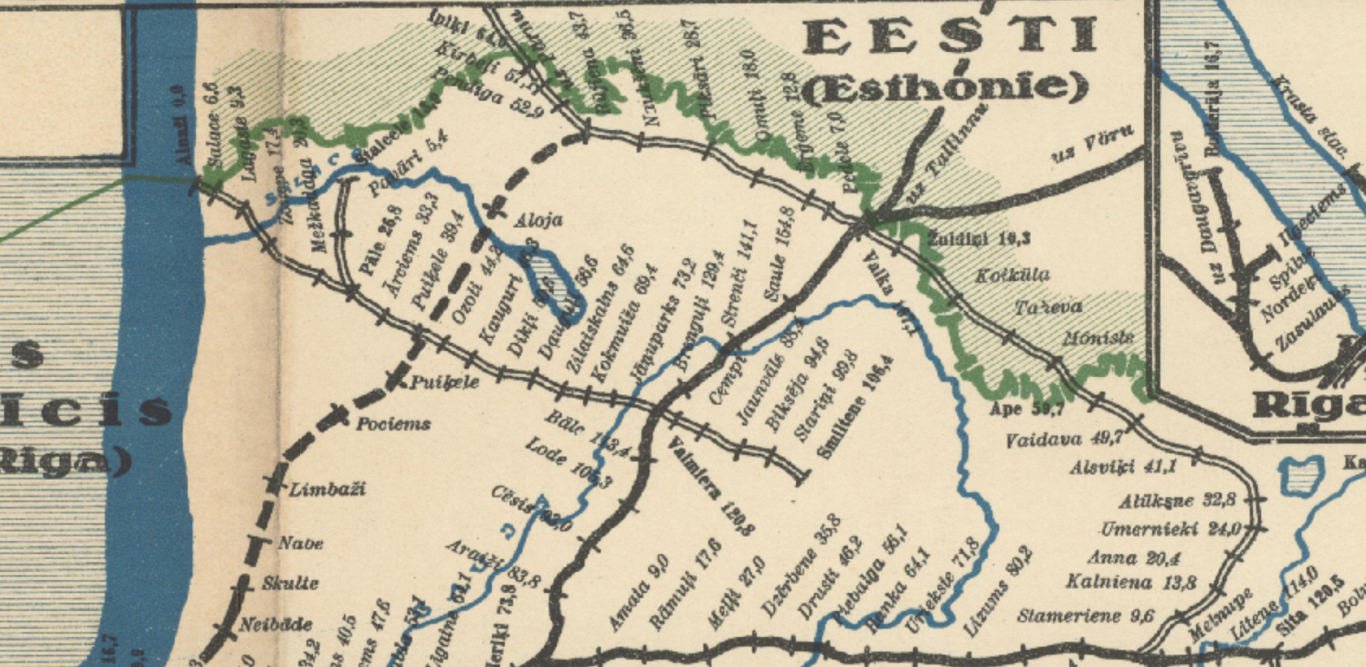

The work of the Latvian–Estonian border commission was drawing to a close, and its head Stephen Tallents was to publish an offer for the new border between the two countries soon. The stakes were high, deciding the fate of Valka/Valga and the towns of Ainaži and Ape situated near what is now the border between Latvia and Estonia.

Would Tallents find a solution?*

As early as summer 1919, Latvia and Estonia agreed to set up a border committee. It initially consisted of representatives from both countries. Starting from the very first meetings, there was a consensus that the new border must be based on ethnic principles. But this idea, which seemed honest in theory, created numerous problems in practice. Of course, under the Russian Empire neither Estonian nor Latvian speakers had chosen where to live based on ethnicity.

In many parishes and villages, it was likewise difficult to discover which was the larger ethnicity. Often, Estonians and Latvians numbered very evenly. Not to mention that there were many mixed families that could be considered either Latvian or Estonian. To add to the confusion, there were also Germans, Russians and Jews who, depending on the exigencies of the situation, could call themselves a separate nationality or instead say they belong to Estonia or Latvia. The situation was further exacerbated by both countries' claims on Ainaži or Hainaste and Valka or Valga – the economic value of these towns seemed to outweigh any ethnic concerns.

It should be noted that until February 1920 the Latvian Provisional Government was not interested in solving the issue of the fledgling country's borders. Fights against the mercenary army of Bermondt and the Bolsheviks in Latgale meant that Latvia's position was much weaker than Estonia's.

At the time all the contested territories were controlled by the Estonian army. As more intense work resumed in February 1920, it became clear neither Latvia nor Estonia were willing to concede the tiniest speck of land.

That's why on March 22, 1920 both countries agreed to ask neutral Britain to send an arbiter to help resolve the issue.

Both sides agreed to have British Colonel Stephen Tallents, a former British Commissioner for the Baltic Provinces before and the civil governor of Rīga during the interregnum between the governments of Kārlis Ulmanis and Andrievs Niedra in summer 1919.

Murky borders*

In the beginning, Tallents' commission sought to ascertain the ethnic make-up in the border areas, just like its predecessor did. But British officers soon came to realize they're part of a game where neither the rules nor the participants are clearly marked. At a time of democracy and national sovereignty, not just governments but also the press and local residents partook in fighting to have the borders drawn as they saw fit.

Soon enough, the committee found that both parties would turn down any argument set forth by the other side.

For example, the Estonian government had carried out a census in the contested territories. But the Latvian government instantly protested against using this data, as it thought that Estonia used the military control it had over the territories to tamper with the information it had collected.

As concerns the biggest apples of strife, the towns of Ainaži and Valka, the Latvian side said that the tight economic ties the towns have with the cultural region of Vidzeme outweigh any ethnic concerns. Estonia meanwhile argued that Valka/Valga is organically tied to Tartu and Southern Estonia, not Latvia. And that to the south of Valka/Valga there's marshland and woods, while beautiful fields mark the Estonian side. The Estonian south is the natural bread supplier for Valka/Valga and without it residents would be at risk of starving. The Latvian side wanted to upset the argument with statistics saying that Latvian not Estonian livestock is consumed more in Valka.

The press, of course, was more than an idle bystander. Each step of the border committee was accompanied with articles by nationalistically minded Latvian and Estonian journalists, who flattered, made threats, complained, protested, and spread rumors and threw insults. Of course, politicians and journalists observed the fight over the new border at a safe distance, in the big cities. So maybe the situation should be studied "on the ground", learning what the locals think? This plan seemed the most promising for the members of the committee, until they learned that they were as unlikely to ascertain the truth on the spot as from a distance.

Everywhere the Tallents commission went, they were greeted by a Latvian or Estonian local who claimed to be explaining the "true situation". At other times, the committee saw small demonstrations by the locals eagerly showcasing their Latvian- or Estonian-ness. A few steps away, however, they'd meet the demonstrators' neighbors who would tell them the exact opposite.

While activists who met the commission were often friendly, people at homesteads were more forthright. Locals knew the rumors from the Latvian and Estonian press, with journalists often having allotted one parish or another to Estonia or Latvia before the actual partition. Committee members therefore had to hear out locals complaining that making their homestead a part of Estonia or Latvia would be sheer stupidity. And there were many cases of people who wanted to become part of one country or the other for reasons independent of their nationality. Farmers found it more important that their homestead remains on the side of the border which had a windmill or a marketplace.

Cutting the Gordian knot*

As spring was drawing to a close, the committee's initial enthusiasm to create a border that would be just and satisfactory to everyone began to dissipate. Neither the Latvian, nor the Estonian government was prepared to compromise. But the Brits thought they were being cheated on all sides. On May 19, 1920 Tallents said he won't be hearing out any further arguments from Latvian and Estonian representatives. Instead, he'd draw the new border line together with members of sub-committees, as a recommendation the countries could choose to adopt, or not to. If not, it won't be Tallents' problem anymore, and the two governments will be free to to try their own hand in untying this Gordian knot.

Even before this development, committee members had agreed that it'd be impracticable to give Valka/Valga to one of the countries in full.

But finding a way to divide the city based on ethnic principles was likewise impossible. Instead, the committee found a solution in geography, or rather the humble Varžupīte River. Under the proposed arrangement, Estonia would get the city center and the main station that lay east of the river, while the western part of the city and the city's second railway station would fall on the Latvian side. This decision was contrary to the previously preferred ethnicity principle, as it left many Latvians on Estonian soil.

But this allowed to preserve the town as an economic unit, at the same time leaving an important railway node on the Latvian side. To appease the Latvians, the committee left the Ainaži town on the Latvian side. The countryside borders were drawn so as not to separate homesteads and to preserve ethnic borders as much as it was possible.

The border committee published its final proposal, the so-called Tallents' line, on July 1. As expected, none of the parties were satisfied.

The Estonian press was angry about losing Ainaži and separating the Valka/Valga town into two. In Latvia, of course, losing Valga caused the biggest objections – together with the fact that Latvia got the least developed part of the town. At this point in time, the Provisional Government briefly considered regaining Valka with military force. Reacting to this development, diplomat Oļģerds Grosvalds, who was stationed in Paris, sent the provisional government a letter: "If there eventually arise armed clashes with the Estonians, I dare say that our relations with the Allies, which are very good now, would be utterly destroyed and the joint cause of the Baltic nations would suffer gravely. That's why such a confrontation should be avoided as much as possible."

The Tallents Line became a favorite target of criticism in Latvian and Estonian press, and calls were made to refuse it.

Latvian journalists were not below spreading rumors that Tallents decided to give central Valka to Estonia after some Estonians made him drunk.

Still others referred to British colonial practices, admonishing Tallents and his colleagues for treating Latvians and Estonians like African peoples. The two governments paused talks for a moment, but cooler heads prevailed which saw that it is impossible to draw a border that would satisfy both governments and all residents living by the border. On October 19, 1920, the border treaty was signed, using the Tallents line.

*The description of the border commission and its role in marking the new borders is based on PhD theses by Dr. Catherine Gibson - Nations on the drawing board: ethnographic map-making in the Russian Empire's Baltic provinces, 1840-1920. Florence: European University Institute, 2019.

(Another contested point was the tiny island of Ruhnu – its inhabitants, mostly Swedish seal hunters, chose to join Estonia. Read more about this topic in our feature from 2018.)