But I will certainly argue against a follow-up notion: that households should receive some sort of support to (partly) avoid the worst effects of high interest rates.

First a small recap: Latvia is a part of the Eurozone, which means that its monetary policy is decided by the 20 governors of the 20 Eurozone member states plus the European Central Bank’s (ECB) six-person Executive Board, the President of which is Christine Lagarde.

The main goal of their monetary policy is an inflation rate for the Eurozone of 2% “in the medium term” (which means looking a few years into the future – it is thus not a “monetary policy crime” if today’s inflation rate should deviate a bit from 2%.

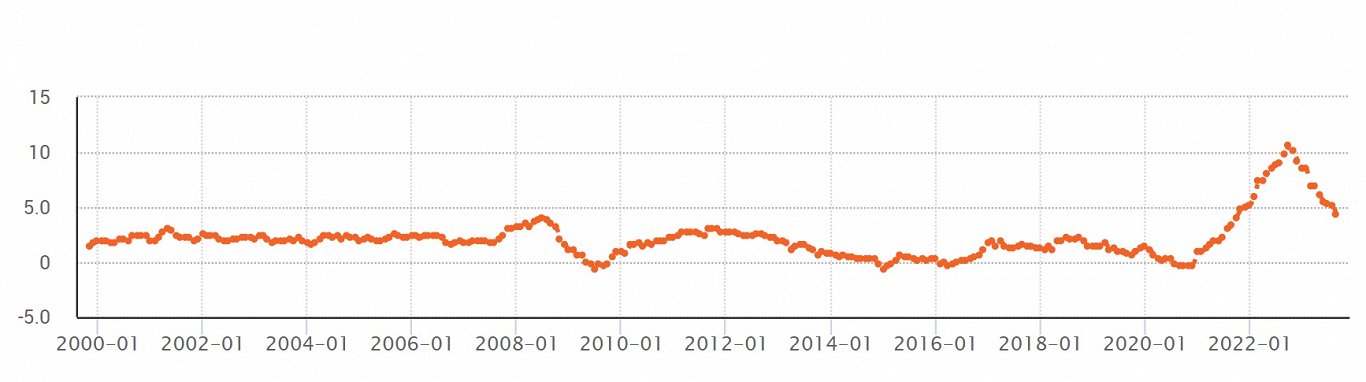

Figure 1 displays the inflation rate for the Eurozone since its creation in 1999. One can observe close to 2% inflation between 2000 and 2007 and again 2010 – 2013 as well as 2017 – 2019. The credit boom that several countries witnessed in 2006-2008 saw inflation increase; then the following bust saw inflation go negative as it did in 2015 and 2021 (Covid 19-related).

Figure 1: Inflation in the Eurozone 1999-2023

Source: Eurostat

Post-Covid 19, inflation rose above 2% in July 2021 – and then it rose and rose and rose…. The standard monetary tool for the ECB when inflation is rising is to increase its interest rates at which it lends to the commercial banks. Higher interest rates for the commercial banks make these banks raise their interest rates for their lending to you, me and companies. This depresses such lending, leading to less economic activity and less price pressure and thus lower inflation.

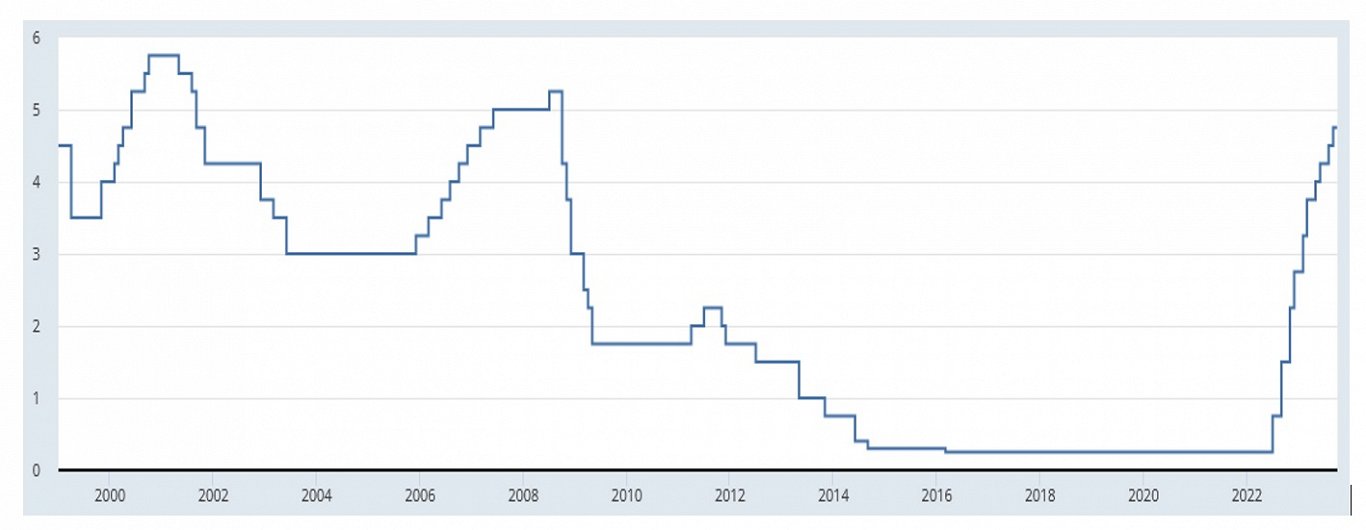

But as Figure 2 shows it took the ECB a really long time to realize that inflation increases in 2021-22 were not just a short blip but a more permanent feature. Only on 27 July 2022 did the ECB start raising its interest rates – a full year after inflation had started overshooting its 2% target.

Figure 2: ECB Marginal Lending Facility (%), 1999-2023

Source: FRED database, St. Louis Fed (Note: The ECB Marginal Lending Facility is the rate at which commercial banks can borrow in the ECB overnight.)

But once the ECB started raising rates, it certainly went fast – since July 2022 and until the time of writing (October 2023), the ECB has raised rates no less than ten times. Three issues stand out:

1) It works – as one can see from Figure 1, inflation is markedly down in the Euro Area (and also in Latvia) although it still has not reached 2%.

2) Interest rates have gone up on ten occasions – but the current lending rate of 4.75% is not historically high. Rates were higher in 2000-01 and in 2007-08. This is the “no” answer to my question in the first line of this article, meaning interest rates are not particularly high.

3) The truly historical issue is that rates came from ultra-low levels. From November 2013 to September 2022 this interest rate was below 1% and that is, as Figure 2 shows, a once-in-a-lifetime event.

I would thus propose the following argument, namely that the long period of low interest rates created in many borrowers’ minds a sort of “entitlement” to low interest rates; that interest rates were “supposed” to be low now and forever. Now, the past year’s wake-up call has created a shock – but it is just a return to what used to be normal.

And why should households receive support to avoid negative but truly normal effects? Also here three issues stand out to support my conclusion from the second line of this article:

a) Before providing a mortgage, banks will have stress-tested a borrower. Can the borrower manage a significantly higher interest rate? If not, no loan would have been provided in the first place.

b) Do also bear in mind that the majority of mortgage holders are not from the poorest segments of the population. Support for the affluent? I think not.

c) Only 14% of households in Latvia have a mortgage so the issue is somewhat limited anyway.

From the first line of my article I also stated that interest rates here are high – the argument can be seen from this link. The three Baltic states have the highest mortgage borrowing costs in the Eurozone and this by some margin. More than one percentage point separates them from fourth-placed Cyprus.

Summing up, interest rates are now higher but not high by historical standards and I see no reason to support people/households against what is normal. But if you have a mortgage, perhaps you should ask your bank why your interest rate is significantly higher than in other Eurozone countries. I guess the bank will say because of different risks (read: Russia) but why not ask, anyway?