The restoration works, worth €300,000 are to be finished by year-end and will encompass only the 115-meter museum building, a sloped, narrow construction the shape of an oblong in the place where a barbed wire fence once stood to keep prisoners from escaping.

Architect Līga Gaile, who is overseeing the reconstruction, says it'll be the first time it's renewed since 1967. She says it'll be simply gentle refurbishment without altering the character of the place.

"It has aged gracefully for the last fifty years.. The concrete facade has been damaged, with moss growing over it. It is being cleaned cosmetically. But there'll be some novelties as well," she tells Latvian Radio.

The novelties she's referring to is a new exhibition dedicated to the history of the former Nazi camp and of the memorial itself. It will be based on decade-long research by a team of historians lead by Uldis Neiburgs.

Memorial for Nazi war crimes

The Salaspils Memorial was built to commemorate the atrocities carried out by the Nazis at the camp; the scale of these atrocities was however amplified by Soviet propaganda.

In 1959 a competition was launched to create the memorial, a time when the Soviet Union launched a massive campaign of building military cemeteries and memorials. The Soviets stressed the war crimes of Nazi Germany but remained silent about their own.

A team of artists was eventually completed, and some were invited from outside the competition.

Ivars Strautmanis, an architect who died recently, wrote a book dedicated to the memorial. He said that he came up with the sloped construction - one of the most impressive details of the memorial - at home as he was raising a concrete beam using a lever.

For seven years a team of artists exchanged their ideas, fighting for how they thought the memorial should look. Only seven of the initial 20 artists saw the project through to its end - architects Gunārs Asaris, Oļģerts Ostenbergs, Ivars Strautmanis, Oļegs Zakamennijs and sculptors Ļevs Bukovskis, Oļegs Skarainis un Jānis Zariņš.

The sculptures are "too pretty"

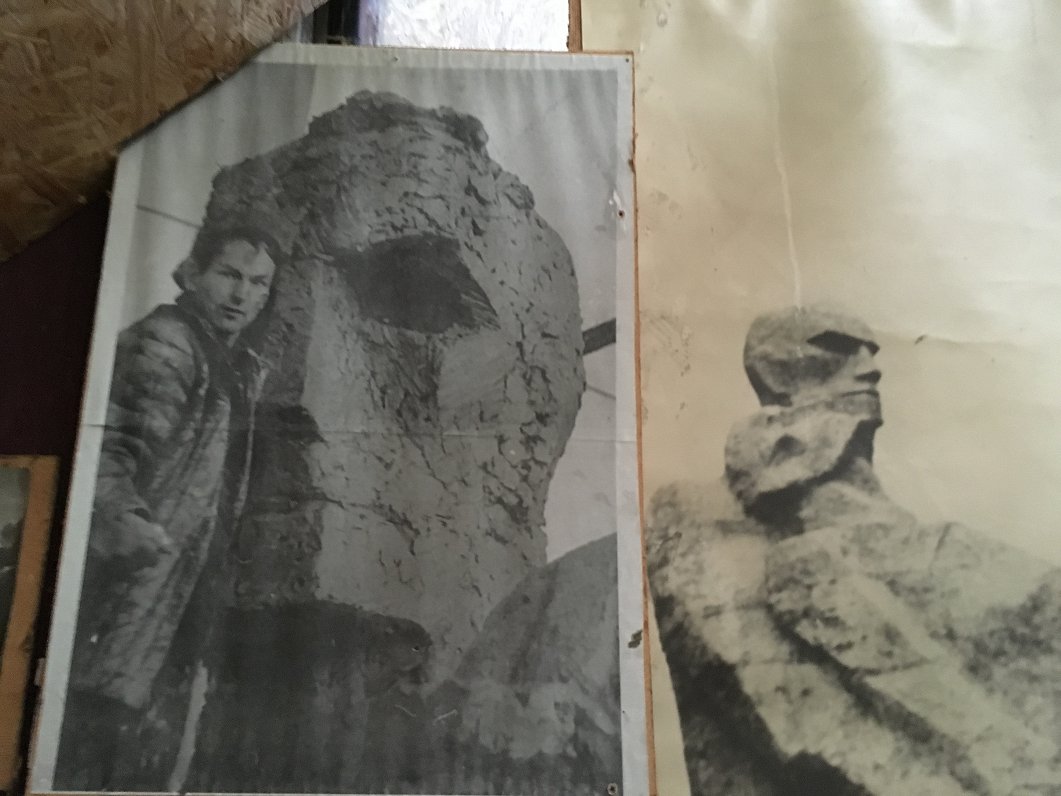

Oļegs Skarainis is one of the two surviving people of the seven artists. He talks slowly but gladly remembers the years he spent working on the Art Brute sculptures he worked on.

"They had [similar memorials] elsewhere in Europe. In Poland, Yugoslavia, Germany... we were up to date with the developments," he says.

During the competition the artists had visited the site and decided that it should work with the concepts of land and way (zeme and ceļš).

While in all content about his work, he says the rough-edged concrete sculptures could have been more uneven. The current ones are "too pretty".

"Be that as it may, the result is good.. This memorial is meant to remind people not to repeat their wars and the stupidities they do. So that it may never happen again," he says.

The memorial has since been included in the Lativan Culture Canon. On the website dedicated to the canon, the architect Kristīne Budže praises the memorial as a modern complex.

"The Salaspils memorial stretching for 25 hectares is one of the largest memorials in Europe and a vivid example of late 1960s Brutalist architecture."

The Salaspils camp has been variously described as a death camp, forced labor camp, concentration camp or prison camp.

A book on the Salaspils camp, titled Behind These Gates The Earth Moans and co-authored by Kārlis Kangeris and Uldis Neiburgs, was released last year.

It purports to give an account of events at Salaspils based on historical evidence rather than questionable facts circulated during the Soviet era, including a startling conclusion that around 2,000 people met their deaths at the camp rather than the figure of up to 100,000 sometimes claimed in the past.

According to the new history, between 21,855 and 23,035 people were imprisoned in Salaspils camp. Of those, 11,000 were classed as "in transit".

At any one time around 1,800-2,200 people were interned there and approximately 2,000 inhabitants of Salaspils camp died or were executed in the period from May 1942 until September 1944 when the camp was active, the book finds.

"The ruthless, brutal and inhumane living and working conditions in the Salaspils camp differed little from concentration camps in Nazi Germany... the actual number of prisoners and deaths is vastly different from the numbers mentioned in Soviet historiography, but this fact does not minimize or relativize the responsibility and guilt of the Nazi regime and any local collaborators," said a handout at the launch event for the book.