It’s often in more obscure or out-of-the-way institutions that you stumble across the tales and artefacts that fit less neatly into the national storyline, the revealed preferences that show what the culture really values or fears deep down.

The Latvian Museum Association lists over 160 operating museums, meaning that there is one for around every 12,000 Latvians. This includes the well-funded tourist attractions of Riga, but just as in any country, there are a lot more museums that are remote, rarely open, dedicated to almost forgotten fragments of history, or that would simply be baffling to anyone from elsewhere.

It’s this latter group that this series is dedicated to: the wonderful unusual museums of Latvia. And we’re defining “unusual” basically however we like – it could mean unique, slightly uncanny, incredibly Latvian, or just, well, rather unusual.

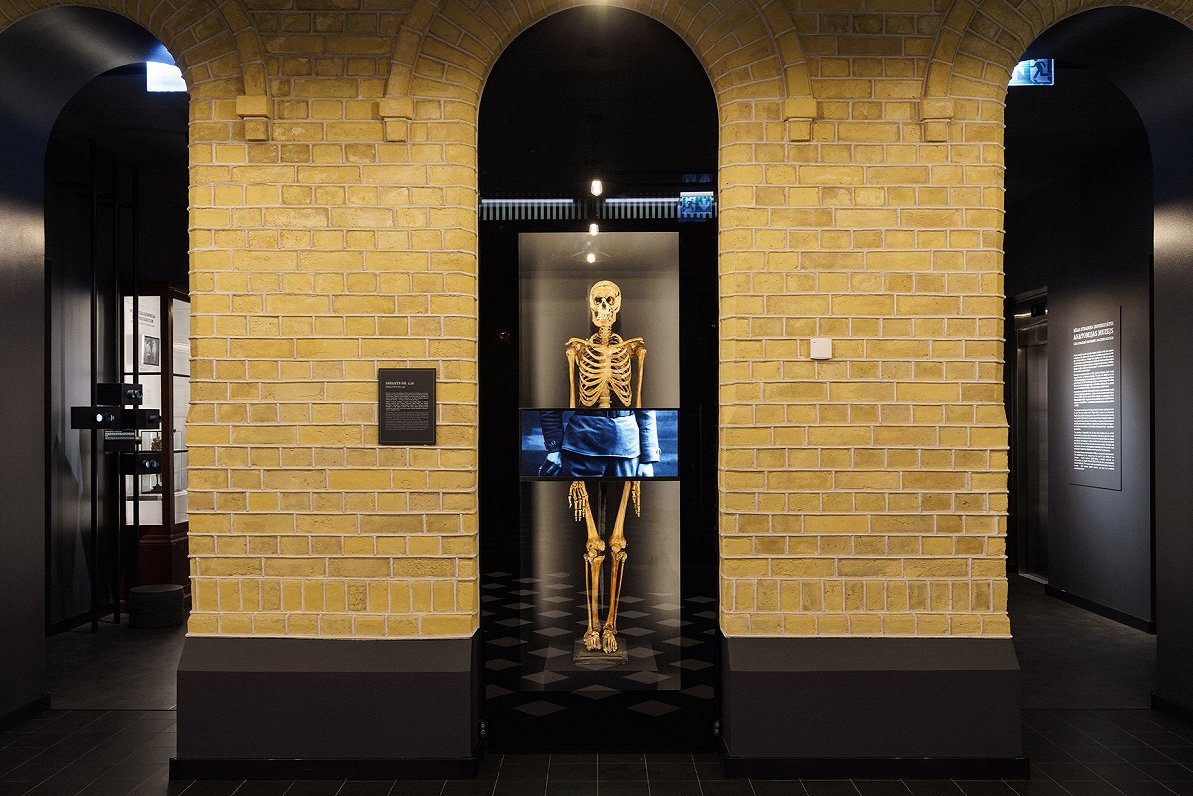

RSU Anatomy Museum, Riga

It’s one of the most recently revamped museums in Riga, open in its current form only since 2021, but the RSU Anatomy Museum has a collection that has changed little in the last hundred years. If the origins of the museum in Europe are usually traced to private collections held by aristocrats and royals, the Anatomy Museum gives us a perfectly preserved glimpse of something that is even older: education for medical professionals. How are those tasked with patching up our bodies and potentially saving our lives meant to learn just how they really look and how they function (or malfunction) under their outer coverings? As the museum’s website puts it: “Everyone has a body, but how well do we know it?”

Well, to teach aspiring doctors, at least until very recently, you ideally need to have at least one authentic skeleton, a comprehensive selection of bodily bits and pieces, and those parts that will end up decaying arrested in a representative state – and it would obviously help to have a few that are illustratively odd.

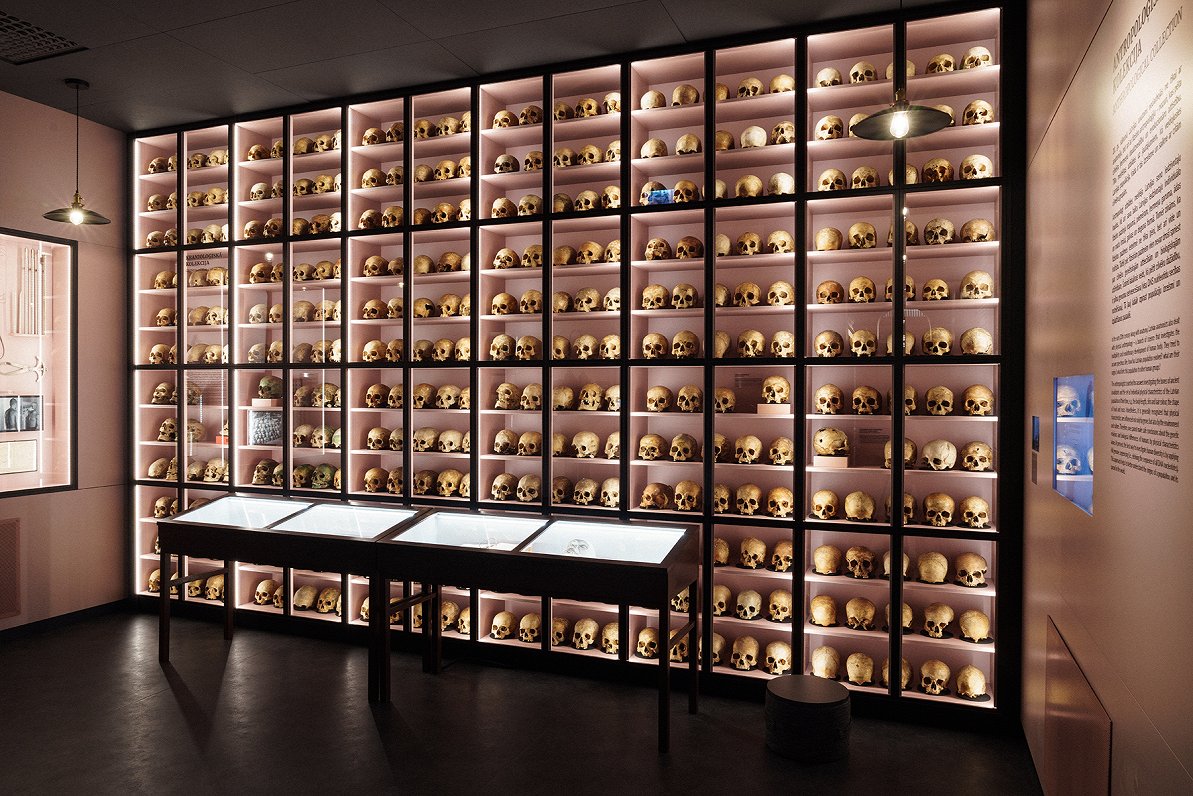

As we said above, we’re defining “unusual” basically however we feel like it in this series – but this one gets on purely on vibes. Cabinets of cheery-looking skulls, disassembled bones of all kinds and conditions, the putty-like squiggles of preserved brains, various organs floating in liquids of troubling colours. Spines and clavicles curve gently like the horns of some exotic animal. And that’s just the ground floor – the basement holds more alarming sights.

The Anatomy Museum’s extensive collection of skulls and bones was initiated in the early 1920s, and the vast majority of its holdings date from the interwar era of Latvian independence. Formerly held in the grand bedomed Anatomy and Anthropology Institute (widely known as the Anatomicum) at the far end of Kronvalda Bulvāris, since its multi-million-euro redesign it’s been housed in a diminutive former stable building nearby.

The fact that the collection is almost exactly the same age as the Latvian state is no coincidence: the University of Latvia was established in 1919, just a year after independence was declared, and this collection was assembled to serve the university’s newly minted Anatomy Institute – the first to exist in Latvia – by a Swedish professor, Gaston Backman, recently arrived from Uppsala. It operated as a museum, but many of the preparations were used by students in the lectures held in the Anatomicum. Backman was assisted in his work by Latvian Jēkabs Prīmanis, who later ran the museum for many years. It’s now associated with the medical institution Riga Stradiņš University, which broke away from its parent in the 1950s.

As the museum’s education project manager Kaspars Zaltāns explains, a frequent response from visitors is to praise the accuracy of the replicas (all are real) – in a more squeamish age with more ethical qualms, many people will rarely if ever have seen genuine human body parts in this condition. And with advancing virtual reality technology, it’s possible that in the future they will see limited use even in medical education. The museum even sold skeletons to private customers (39 in total by the outbreak of World War II), seemingly cobbled together on a rather mix-and-match principle.

Most of these bones came from bodies unclaimed by loved ones, but not all were anonymous: the first complete skeleton obtained was known to be Jānis Teodors Lukstiņš, a 27-year-old who had promised his body to science and shot himself on a central Riga street in 1925. A popular but apparently untrue tale asserted that he was himself a medical student who had committed suicide on the Anatomicum steps after failing a test. He’s joined among the museum’s artefacts by a rather larger skeleton: a whale vertebra gifted during Soviet times by another socialist republic and used as a bench by the members of one student association.

However discomfiting some of the stories may be, the lack of any colonial context means that the Latvian museum has avoided criticism directed at similar institutions in Western Europe. The founders of one of the closest analogues to the Anatomy Museum in Europe, the Museum Vrolik in the Netherlands, conducted many of their studies using bodies from the imperial possession of the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), and the museum has recently returned Maori remains to New Zealand.

But in a newly established state intended as a homeland for a historically downtrodden people, the onus for the research done here was on finding proof of their own distinctiveness and importance – pinning down supposedly archetypal Latvian characteristics. “It’s not looking outside, it’s more looking inside,” Zaltāns says.

Prīmanis wrote an academic treatise on the physical builds of characters invoked in the dainas – or Latvian folk songs – that were collected in their tens of thousands by Krišjānis Barons, and the museum features some of the copious figures and measurements derived from scientific expeditions conducted throughout the country. Pride of place goes to the vital statistics of the national poet, Rainis, recorded shortly after his death in 1929. (As well as important data about the capacity of his lungs and the height of his ears, he was found to have an unusually heavy brain – although, as the museum staff will tell you, the weight of a person’s brain has no bearing on their intelligence).

Strolling around the museum is a profoundly surreal aesthetic experience – it’s impossible not to be struck by the sheer strangeness of the coils and nubs and containers of our insides. This is most of all the case with the remarkable tinted corrosion casts of bronchial trees, lurid but delicate shocks which could be taken for some kind of deep-sea algae or a computer-generated fractal model.

These quasi-artistic qualities make it appropriate, then, that the museum has prioritised imaginative collaboration with creatives since its reopening. These have included over a hundred mischievous-looking miniature ceramic figures placed throughout the collection by British artist Paddy Hartley, and the work of Baiba Rībere, who sews images of the unknown faces found in the museum’s preparations onto a backing of medical gauze. The current resident is Ivars Šteinbergs, a very contemporary Latvian poet known for his formally eclectic and playful verse, who has written 28 poems dedicated to different holdings and themes of the museum.

These include the so-called “jar babies”, perhaps the most viscerally disturbing part of the museum, which visitors are warned about before venturing downstairs: foetuses, many with various developmental defects such as conjoined bodies or shrivelled heads, floating in jars of formalin. Nearby are yellowing scraps of human skin with caricatures of ships and scantily clad ladies: hundred-year-old tattoos, examples of a practice limited at that time largely to sailors, prostitutes and criminals.

These were preserved for study largely due to the then-influential pseudo-science of criminal biology, which asserted that personality traits and even moral qualities were heritable and could be assessed from outward appearances – theories that dovetailed with the growing popularity of eugenics in interwar Europe (Prīmanis himself briefly headed the National Life Force Research Institute, an organisation that promoted eugenic thought in Latvia).

After first being placed in water, and having had subcutaneous fat layers removed, the tattoos were steeped in alcohol; varnish was then applied, and the dried results look like doodles in the margins of mouldering old ledgers. In one of his poems, Šteinbergs imagines a moonshine-swigging sailor named Kolchak, “a grey tombstone tattooed on his arm”, drunkenly antagonising the musicians of a Grāvju iela boozer; stabbed with a pocket knife, “he fell into a puddle of mud/ cool as sour cream”.

Describing his assumptions before starting work on the museum, Šteinbergs wrote “I thought I would be telling a story of mortality. However, it turned out to be a story about people’s lives, real and imagined, about heart-warming, funny, tragic lives”.

If you'd like to visit the museum yourself, you can find details of opening times and exhibitions here: https://am.rsu.lv/en