More about the cycle of events can be discovered at the website https://www.gramatai500.lv and for more about the Latvian National Library and its constantly changing exhibitions and collections, visit: https://www.lnb.lv/.

"Do not touch what is not yours " – historical words of warning for book thieves

As we steadily "trace the footsteps of books", our curiosity is piqued about the fate of rare and valuable editions, trying to reconstruct the long biography of each book. Can this even be done? And what evidence do we have of previous owners and readers? The book itself is keeping quiet, it is a silent witness.

"Books have their own fate according to the capacity of the reader" (Latin: Pro captu lectoris habent sua fata libelli) - so said the Latin Roman Terentianus Maurus in the 2nd century. Many people know the final line of Terentianus' phrase and find it endearing, but the statement actually has a deeper meaning, namely the fate of a book is determined by the intellectual capacity, interests and values of its reader/owner.

However, there is reliable evidence of the adventurous and eventful journey of books to the present day. The best way to discover the fate of a volume is through provenance or ownership records. The provenance of a book is very important, telling us what people were interested in reading, the circulation of books in society, the ways in which books are acquired, bought, sold, donated, lost, exchanged and inherited. Usually, the ownership details are rather brief: the name, the year, the place are all recorded in the book. However, occasionally, it is a rather rare occurrence to find very unusual ownership records: warnings to book thieves.

The content of these records is rather eccentric and they are usually given a metrical form.

The desire to protect one's books with a wish, originally written in Latin, or more frequently, a verse has been found in written records tracing back to the 12th century; later, many anti-theft records were written in German, and in the 16th–18th centuries throughout Europe, both in England and in the German cultural zone, in Poland and Norway.

Moreover, the rhythmic records are related content-wise, so that a few familiar source texts were used, and formulas that were partly folklorised. Verses were adapted and localised, modified according to the poetic skills and preferences of the author of the record. Books from the late 15th – 18th centuries with curses to deter thieves have also ended up in the collection of Latvian historical books. Some were written by Rigans from that era, others by unknown and unidentifiable authors (i.e. owners of the books).

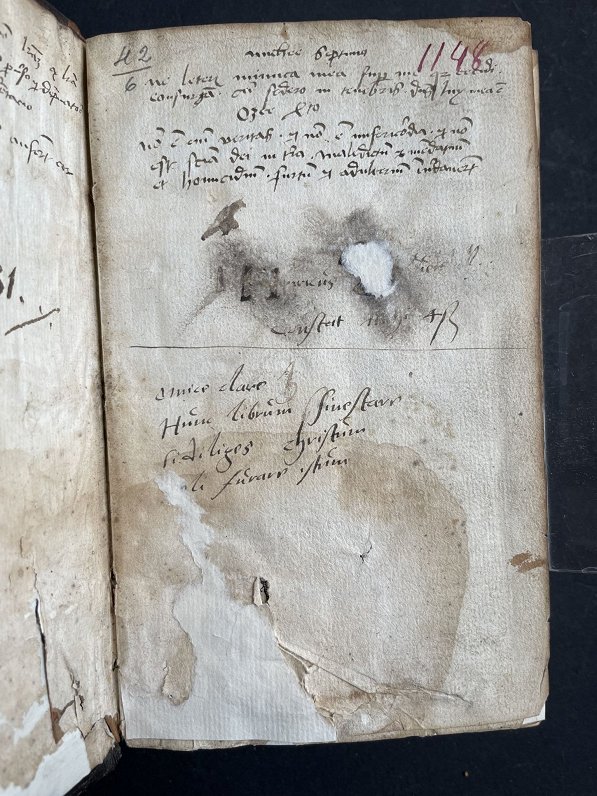

"Dear friend, Do not touch this book, If you love Christ, do not destroy it". Record from early 16th century. Erasmus Roterodamus. Paraphrases. Moguntia, 1522. Photo: ALUL

It is worth noting that as early as the 1920s–1930s, the prominent historian and director of the Riga City Library, Nikolaus Busch (1864–1933), started in-depth research of the book collection. Thanks to him, the most interesting anti-theft records in books were found and published posthumously (1937), which can now be found in the LUAB's collection of rare books.

Writers wish to protect their books in various ways. Many records appealed to Christian values, they pleaded and urged: "Dear friend, this book is not to be touched, If you love Christ, do not steal it" (early 16th century); records with variants of this popular Latin verse have been found in Germany, England, Norway, the Czech Republic.

However, harsh words were more popular. To scare away the scoundrel who might covet and take another's book, the owner would write curses. These were written to guard the book: 'give it back or the devil will tear/rip your skin' (early 16th century). Boris Depken (1590–1649), a merchant in Riga, wrote on the front page of Luther's Home Sermons (1570), below the sign of the cross:

"Boris Depken owns this book,

If anyone finds it, let him have it back.

You must pass it by

and leave my book standing in peace,

If you do, however, take it later,

Then you will be food for the ravens."

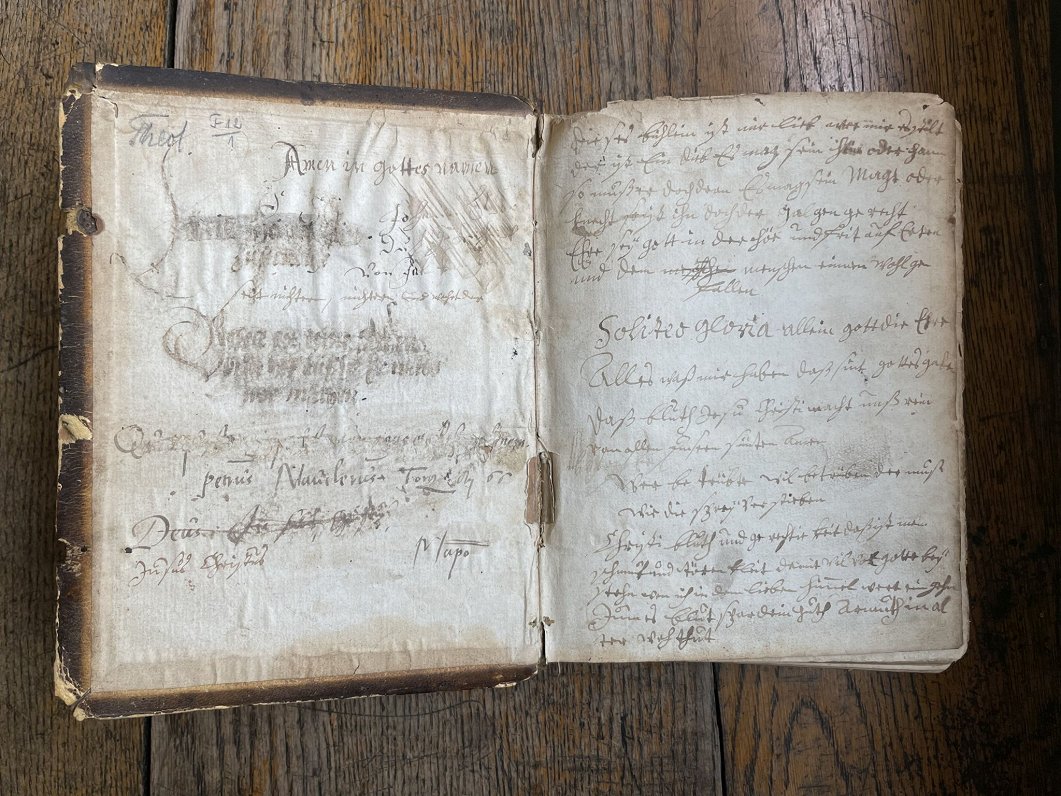

Johann Heinrich Müller, presumably a resident of Riga in the early 18th century, continued in a similar vein, but in a more convoluted and emotional manner, writing on the blank pages inside the front cover of his volume of F. Melanchthon's Articles of Faith (1558):

"In the name of God, Amen

This little book is dear to me; whoever steals it is a thief, whether it be a hen or a cock, he must go away; whether it be a female or a male, he should be sent to the gallows. Glory to God in the highest, and peace on earth, and goodwill toward men.

Glory to God alone; all that I possess is given to me by God,

The blood of Jesus makes us clean from all our sins. Amen.

(...) The blood and righteousness of Christ is my glory

(..) so shall I follow God, if I honour the dear heavens. The blood of Jesus is your goodness, poverty brings misery in old age"

The rhythmic curses against book thieves echo several important cultural and historical traditions and practices. Firstly, there is the legal aspect. It is evident that since the Middle Ages, anti-theft records have the aim of scaring and threatening with severe, cruel and humiliating public punishments those who have coveted another's book and dared to take it and are unwilling to return it to its owner. The threat is to be hanged on the gallows (Galgen in German), i.e. the gallows knot.

The theft of a book is therefore considered to be a rather serious property crime.

We can conclude that a book is of considerable value to its owner, not only spiritually but also materially. According to the law of the time, the offence is punishable according to the value of the stolen item, which is why various ancient legal sources (Saxon Mirror, 13th century, etc.) mention grand theft and petty theft. The petty thief is punished by beating, while the grand thief (who has stolen more valuable property) is punished with the most shameful public punishment: hanging by the gallows.

Memories of the city's places of punishment, punishments and crime are also echoed in German proverbs: ‘gallows are suited for the thief' (German: gleicher Dieb, gleicher Galgen); 'the gallows are empty and the city is full of thieves' (German: der Galgen ist lähr und die Stadt ist voller Dieb. 1686).

Neither does this punished criminal deserve a dignified burial; anti-theft curses capture a dramatic reality: ravens pecking and tearing at the flesh of the punished book thief on the gallows. The epigram of the Roman poet Horace (65-8 BC) on punished criminals is echoed here and revived in a later era: those hanged on the cross "have become food for the ravens" (Latin: in cruce pascere corvos).

The anti-theft records imply a literary and moral-ethical tradition rooted in Christian theology. The curses directed at book thieves echo the voice of the Old Testament prophet Moses, whose curses are harsh against transgressors of the Law (Deuteronomy 28). At the same time, the anti-theft curses certainly have the characteristics of household magic.

The study of the provenance records of books has led to a diverse and vivid series of cultural and historical reflections.

The question remains: did the records succeed in protecting the precious books from an unfortunate fate?